- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

It’s been a year since the Department of Interior released the first volume of its federal investigation into Indian boarding schools. Native News Online Senior Reporter Jenna Kunze, who’s written more than half of the 175-plus stories we’ve published on Indian boarding schools, takes a look at what’s happened since the groundbreaking report was published, and what’s on the horizon.

A year ago today, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) released Volume 1 of its Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report detailing the history and ongoing legacy of the federal government’s 150-year policy of forcibly assimilating Native American children into white culture by sending them to Indian boarding schools.

The investigation, a key part of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative launched by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland in June 2022, set primary goals to identify boarding school names and locations, burial sites, and the names and tribal affiliations of children interred at each location.

As part of the investigative report, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Bryan Newland—the report’s author—made eight recommendations to the Secretary of the Interior to fulfill the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, including:

- Identifying surviving boarding school attendees and documenting their experiences.

- Supporting the protection and preservation of boarding school sites where the federal government has jurisdiction.

- Authorizing agencies disinter or repatriate any remains of Native children—with direction from their respective tribe, community, or family—discovered in marked or unmarked burial sites associated with the Federal Indian boarding school system.

A year later, the DOI has made substantial progress on at least two of Newland’s recommendations, while others remain works in progress that are being advanced by the federal government and, in some cases, by non-governmental organizations, tribes and volunteers. As well, the mainstream media has put a bright spotlight on the issue for the first time ever, creating awareness of boarding schools and their role in the assimilation and harm of Native Americans over the past century and a half.

The leader of the nonprofit Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), the organization at the helm of truth and healing work around Indian boarding schools for more than 10 years, says the work over the past year has been an important beginning to what will ultimately be a years-long process.

“It’s the first step of the federal government recognizing the harms that they've created through the boarding school era, and this step is absolutely necessary for us to continue to research and to collect records and bring together survivors so we can hear their testimonies,” NABS CEO Deborah Parker (Tulalip) told Native News Online. “Without this first volume, folks wouldn't understand where to go, because you can’t read about this history in national curriculum.”

What the report said

The 106-page report penned by Newland found that the federal government operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states, including Alaska and Hawai’i, between 1819 and 1969. The DOI also identified more than 1,000 additional federal and non-federal institutions that didn’t fall under its definition of “federal Indian boarding school.” Those additional institutions included Indian day schools, sanitariums, asylums, orphanages, and stand-alone dormitories that worked similarly to assimilate Native youth into white society.

The government's stated aim with the Indian Boarding School policy was to “subdue” the Indian by replacing Native culture with white culture, and to eventually change “the Indian’s economy so that he would be content with less land,” the DOI report quotes from old federal documents.

The report also details the conditions students experienced at school, including: manual labor, corporal punishment, infrastructure deficiencies, poor diets, and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. More than 500 children died at 19 of the schools, and the DOI identified student burial sites at 53 schools — numbers that are expected to rise as the Department of the Interior continues its research.

The report lays the groundwork for the continued work of the Interior Department to address the intergenerational trauma created by policies supporting the historical federal Indian boarding school system. It reflects an extensive and first-ever federal inventory of government operated Indian boarding schools, including summary profiles of each school and maps of general locations of schools in current states.

“Federal Indian boarding school policies have touched every Indigenous person I know,” Secretary Haaland said in a statement to Native News Online. “Some are survivors, some are descendants, but we all carry this painful legacy in our hearts. Deeply ingrained in so many of us is the trauma that these policies and these places have inflicted.

“Through the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, we are undertaking a comprehensive effort to recognize the legacy of boarding school policies with the goal of addressing their intergenerational impacts and to shed light on the traumas of the past. To do that, we need to tell our stories.”

What’s been done

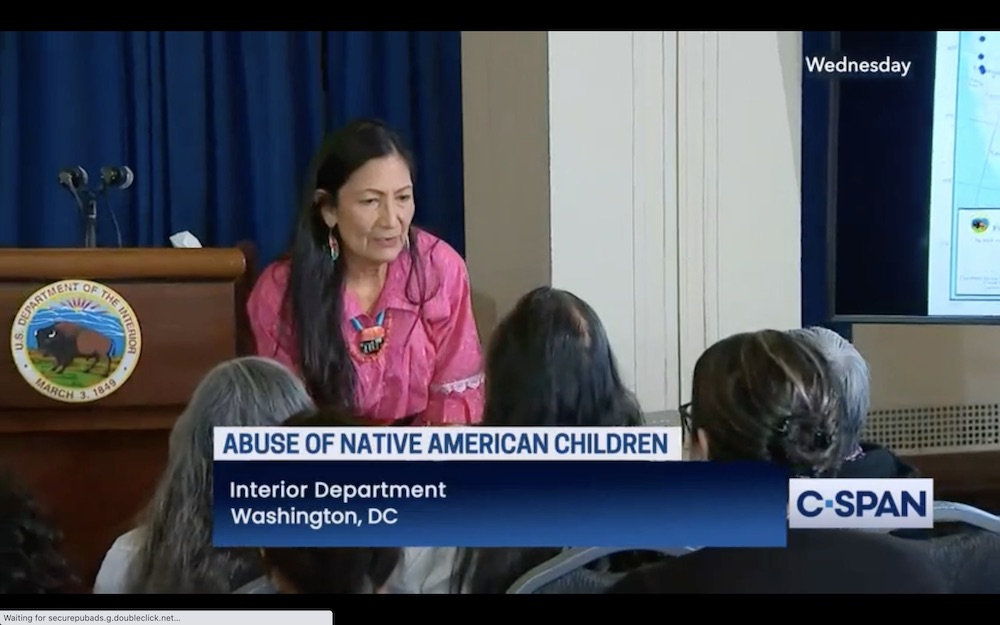

As a response to the report’s recommendation to “document Federal Indian boarding school attendee experiences,” Secretary Haaland launched The Road to Healing tour last May, a year-long commitment to travel across the country to hear from boarding school survivors and their descendants.

To date, Haaland and Newland have held six hearings in: Anadarko, Oklahoma; Pellston, Michigan; Mission, South Dakota; Gila River Indian Community, near Phoenix, Arizona, Many Farms, Arizona on the Navajo Nation; and Tulalip Indian Reservation, near Seattle, Washington.

During those sessions, hundreds have shown up at each stop along the Road to Healing tour to hear testimony from other survivors and their descendants about the intergenerational trauma that began during the boarding school era. At the events—which have typically run upwards of five hours— dozens of survivors shared stories about horrendous physical, emotional and sexual abuse they endured, while descendants spoke of the lasting impact on their families and communities.

One survivor, 78-year-old Rosalie Whirlwind Soldier (Sicangu Lakota), testified at the third Road to Healing stop on South Dakota’s Rosebud Indian Reservation that growing up in boarding school, she didn’t know what love felt like. She recounted a story of a nun sending her and another classmate into a dark cellar as punishment, where they were forgotten about for “days,” subsisting off pickles that were stored down there. She also spoke of nuns chopping her long braids, powdering her in DDT pesticide, and calling her a “devil-speaking person.”

“I thought there was no God, just torture and hatred,” Whirlwind Soldier said. “We went through what the Jews went through as Lakota people. The only thing they didn’t do to us is … gas us.”

At the Road to Healing sessions, Secretary Haaland and Assistant Secretary Newland often just listen, sometimes jotting down notes. Even so, Newland has spoken about how tough it is on both Haaland and him to hear the stories.

“People stand up in a gymnasium full of people and talk about the worst things that have happened to them,” Newland said during a recent talk at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

“I want you to know that I’m with you on this journey and I will listen,” Haaland said in her opening remarks at the most recent Road to Healing stop in Washington late last month. “I will grieve with you. I will weep with you and I will feel your pain, as we mourn what was lost. Please know that we still have so much to gain. The healing that can help our communities will not be done overnight.”

A comprehensive effort

Since last May, the federal investigation has made significant progress on two of its primary objectives: collecting the oral histories from survivors, and naming and locating boarding school sites throughout the country. They were able to glean much of this information from NABS, which shared its decade-long work with the Department of Interior as part of a Memorandum of Understanding the two groups signed in December 2021, and is ongoing.

In the last year since the investigation was released, former boarding schools schools have begun using ground penetrating radar technology to search for unmarked graves; a bill has again come before Congress that would establish a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies; and organizations have doubled down on work to retrieve and digitize school records that will help account for every child who attended boarding school, including those who died there.

In late April, the National Endowment for the Humanities committed $4 million to support the digitization of records from the federal Indian boarding school system, and to create a permanent oral history collection documenting students’ experiences.

And last week, a group of archivists published a list identifying 87 Catholic-run Indian boarding schools that operated in 22 states through the late 1970s, demystifying the process of locating records held by Catholic institutions.

Shining a light

For many Native Americans and First Nations people, the dark legacy of government-run boarding schools was an open secret throughout Indian Country. But beginning with the news from Kamloops in May 2021 and continuing through the past two years, the issue of boarding schools has become more visible to non-Natives in the U.S. and Canada.

Some of that has been driven by the mainstream media, beginning with the global coverage spurred by Kamloops and continuing through the release of the report last year and the stops along the Road to Healing tour over the past 12 months. As well, boarding schools have been topics of storylines in national television shows and the focus of podcasts, including the new “American Genocide” produced by Illuminative, a Native-led nonprofit.

Last week, First Nations journalist Connie Walker won two of the biggest prizes for journalism in North America—the Pulitzer Prize and Peabody Award— for her podcast ‘Stolen: Surviving St. Michael’s’ that explores the abuse that happened at the Indian residential school her father attended in Canada.

“The issue of the boarding school is very much coming to light,” Parker told Native News Online. “We have a long way to go, but the voices of our ancestors, of our relatives, are coming to the surface. It’s about time. But it will be several years before we reach any sort of model that tells a complete story.”

Currently, DOI is at work at Volume 2 of its federal investigation into boarding schools, due out by the end of this year, according to the Department. That report will focus on identifying: locations of marked or unmarked burial sites on or near former school sites; names, ages, and tribal affiliations of children interred at such locations; and an estimation of federal dollars spent supporting the Federal Indian boarding school system, as well as Native land held in trust by the United States used to support the Federal Indian boarding school system.

“I think for Volume 2, I'm looking forward to what the Interior is learning through hearing the testimonies of our elders and family members,” Parker said. “On the road, the Interior and others have heard some incredibly painful stories, and I'm interested to hear what the federal government intends to do with what they hear. What are the supports that they will bring forward for Congress to understand and to approve? [There is] need for mental health and cultural support and revitalization of our languages and food sovereignty, and all those pieces that were nearly destroyed.”

Former boarding school students, now elders, are also waiting.

Duane Hollow Horn Bear (Sicangu Lakota) is a spiritual leader, educator, and survivor of a federal Indian boarding school in Mission, South Dakota. Hollow Horn Bear testified at the Road to Healing stop on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, where he shared with federal officials about the abuse he endured at the hands of priests as a child in the boarding school system.

In a word, Hollow Horn Bear told Native News Online that he’s “disappointed” about the lack of federal action as a result of the Road to Healing tour.

“All of that work, all of that gathering, all the talks, it was just to collect and store data,” Hollow Horn Bear said. “There was no energy, there was nothing that was going to be done about it. We poured our hearts out and it was just for the collection of data.

More Stories Like This

Committee Advances 20% Increase to Navajo Child Support GuidelinesNavajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement Plan

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher