- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

*Trigger Warning* The situations detailed in this story and survivor testimony could be triggering and harmful to some.

MISSION, S.D.—The mood inside the gymnasium at Sinte Gleska University on the Rosebud Indian Reservation was solemn Saturday morning as Secretary of Department of the Interior Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland (Bay Mills Indian Community), and Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Wizipan Garriott (Sicangu Lakota) entered the room. Looking back at them from folding chairs in the audience were rows of boarding school survivors, tribal leaders, and community members.

Over the next several hours, those survivors would tell the federal officials—descendants of Indian boarding schools themselves—their stories.

October 15 marked the third stop on the Road to Healing Tour, a yearlong DOI initiative intended to collect oral testimonies from survivors of the nation’s more than 400 Indian boarding schools, as well as their descendants. Previous sessions on the Road to Healing Tour were held by the DOI in Anadarko, Oklahoma and Pellston, Michigan.

“As we keep investigating the federal Indian boarding school system and learning about your experience in specific schools, and the overall system, it paints a history records can’t fully provide,” Assistant Secretary Newland said on Saturday.

The tour was announced in May, in conjunction with the Department of the Interior’s release of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. The report details the U.S. government’s 150-year legacy of operating or supporting institutions whose aim was “cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession.”

Newland explained that the Interior’s next steps—in addition to collecting oral testimonies—will include identifying unmarked burial sites across the federal Indian boarding school system, and the total amount of funding the federal government put towards erasing Native culture.

In South Dakota, there were 31 boarding schools, some of which are still operational today. Newland noted he could see one of them—the Bishop Hare Industrial School—”through the window here, across the field.”

Twenty miles away, St. Francis Mission, a Jesuit-run boarding school that shifted into tribal control in 1972, is still operational.

Only the first hour of Saturday’s event was open to the media, and the remaining afternoon was kept private, though a federal court reporter on site transcribed each testimony for the Department's records that, “if asked—under federal law—[the Interior Department] might have to make that publicly available,” Newland said. About two dozen people gave testimonies, according to Interior staff.

PICTURED: Young Sicangu Lakota drummers and singers welcomed Interior staff to their reservation.

PICTURED: Young Sicangu Lakota drummers and singers welcomed Interior staff to their reservation.

What survivors and descendants said

During the five-hour session, survivors recounted boarding school experiences of forced removal from their childhood homes by police and priests, as well as physical abuse, punishment and confinement.

One survivor spoke of being forced by a nun to swallow lye soap as punishment for speaking Lakota. Another spoke of being locked in a basement for an untold amount of time.

As the survivors spoke, Sicangu youth walked around the room, smudging their relatives, and handing out cups of water, coffee, and tissues.

Of the public testimony, only one survivor—Cecilia Fire Thunder (Oglala Lakota)—said that she has healed from her boarding school experiences, and now she’s helping others do the same. She is part of a healing movement led by her former boarding school on the Pine Ridge Reservation, now called Red Cloud Indian School, collecting oral testimonies from former school attendees.

“The only thing that I felt as a little girl watching my mom and dad drive away when they left me at Holy Rosary Mission was … they don’t want me anymore. They don’t love me,” Fire Thunder said, referring to what is now Red Cloud Indian School. “I felt that sense of abandonment, but years later…I understood all those emotions and feelings. I was able to put a word to my feelings, and I was able to let it go. So today, I want to share with you that we can let those things go.”

One survivor, 78-year-old Rosalie Whirlwind Soldier (Sicangu Lakota) testified that, growing up in boarding school, she didn’t know what love felt like. She recounted a story of a nun sending her and another classmate into a dark cellar as punishment, where they were forgotten about for “days,” subsisting off pickles that were stored down there. She also spoke of nuns chopping her long braids, powdering her in DDT pesticide, and calling her a “devil-speaking person.”

“I thought there was no God, just torture and hatred,” Whirlwind Soldier said. “We went through what the Jews went through as Lakota people. The only thing they didn’t do to us is … gas us.”

Although her trauma has followed her throughout her life, she’s chosen to heal from it, Whirlwind Soldier said.

“Sometimes, I’m still to this day quiet, and away from people,” she said. “But I let it go. I let it go. That was killing me.”

Others spoke of intergenerational trauma.

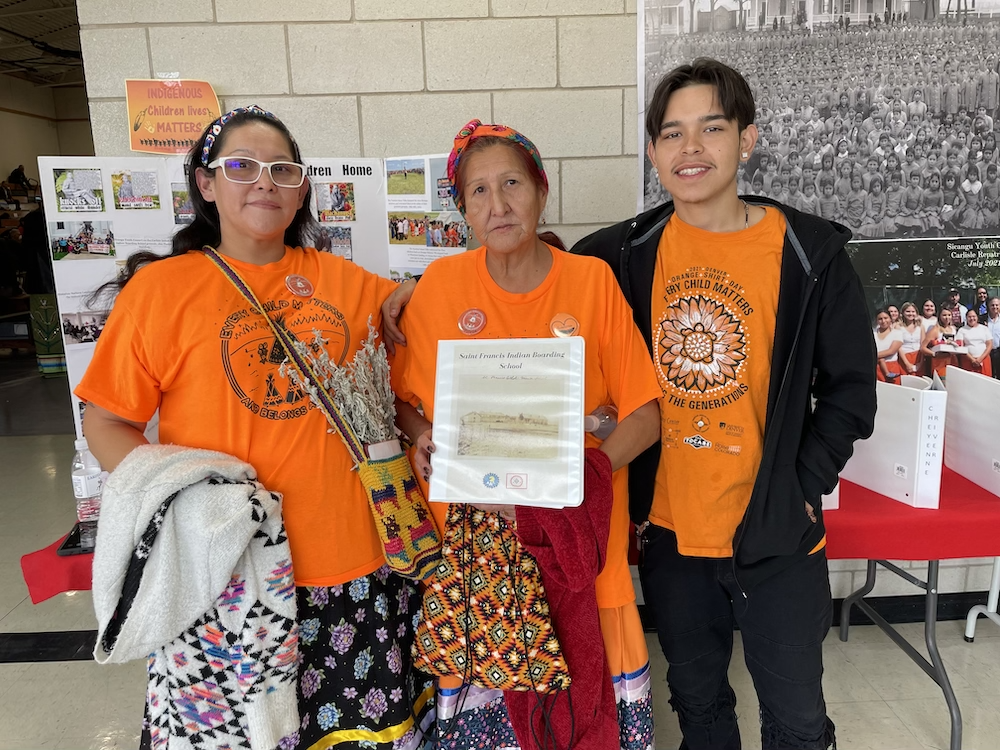

Ruby Left Hand Bull Sanchez, 64, (Sicangu Oyate) drove from her current residence in Denver, Colorado with her daughter and grandson to give testimony. She attended St. Francis Mission school from the age of five until she was 15 years old. Sanchez spoke of physical and emotional abuse that stripped her of her language and her Lakota identity.

“I lost my heritage. I lost my identity between the white world and the Lakota world,” she said in an emotional testimony. “I have to walk that straight line in the middle, and I do it, but it's hard. So I want recompense. I want apologies. I want our language back. I want our land back—I want everything back.”

Left Hand Bull’s daughter, Candice Left Hand Bull Vigil, spoke next. She said that she didn’t know her mother was a boarding school survivor until her mom began sharing her story about a decade ago, which has led to the healing of their strained relationship.

“My whole life I resented her, because I didn't know Lakota culture and … she wanted us to be educated and to know who we were in American culture,” Vigil said. “I’m just sharing because the healing that is happening in my family is not just my mom’s, but it's generational: My mom. Me. My daughter and my son. And she’s teaching us to speak up now and not to be ashamed or embarrassed to talk about these things.”

PICTURED: Left Hand Bull Sanchez (center) beside her daughter Candice Left Hand Bull Vigil and her grandson Andrue Davis. Vigil testified on Oct. 15 that speaking about her mother's abuse has brought intergenerational healing.South Dakota tribal members reflect

PICTURED: Left Hand Bull Sanchez (center) beside her daughter Candice Left Hand Bull Vigil and her grandson Andrue Davis. Vigil testified on Oct. 15 that speaking about her mother's abuse has brought intergenerational healing.South Dakota tribal members reflect

Although many elders remarked that Saturday was a “heavy” day, they also attested to the importance of a movement towards healing, beginning with speaking certain truths aloud.

Renee Iron Hawk (Cheyene River) said that listening to trauma so close to her own triggered feelings of pain, anger, and rage. She knew it would, but that didn’t stop her and her husband—who both attended Bureau of Indian Affairs schools—from making the three-hour drive to attend the listening session.

“We knew what we were gonna experience and feel,” Iron Hawk told Native News Online afterwards. “But yet we still went, because this is what our nation needs. Our nation needs healing. We know it's part of our responsibility as elders to not be afraid to look.”

Duane Hollow Horn Bear (Sicangu Lakota), 73, is a spiritual leader, educator, and survivor of a St. Francis Indian Mission. Hollow Horn Bear testified about the abuse he endured at school during the portion of the event closed to the press. He told Native News Online by phone afterwards he was disappointed not more of his peers gave testimony.

“I feel there could have and should have been more,” Hollow Horn Bear said. “There’s a lot of people within my community that could have shared. When the politicians are there, people get scared off.”

When asked how he himself felt, Hollow Horn Bear said he was on his way to seek that answer.

“Well, I’m on my way to the sweat lodge here,” he said. “I’m going to go and look inside myself.”

Sandy White Hawk (Sicangu Lakota), the president of The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), was also present on Saturday. She said the most positive outcome of the event for survivors was for the government and community acknowledging their grief.

“In the long run, what acknowledgment does is address disenfranchised grief,” White Hawk told Native News Online. “That is the grief that hasn't been publicly acknowledged. Once you've been violated or abused—physically, spiritually, psychological—you learn to cover up that wound.

“The DOI represents that entity that brought the violation, so their presence does add to that acknowledgement. It’s helpful for everyone to hear what our relatives experienced. In a way, too, boarding school was a collective wound and this begins a collective healing because we're all here listening to each other's experience, and that validates that the experience is real. Healing comes from us being present and holding that space for them.”

More Stories Like This

Committee Advances 20% Increase to Navajo Child Support GuidelinesNavajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement Plan

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher