- Details

- By Levi Rickert

Opinion. Today marks one year since the release of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

In many ways, it feels like a lifetime.

On May 11, 2022, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) and Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland (Bay Mills Indian Community) spoke to the nation in an emotional, tear-filled press conference where they unveiled the findings of a nine-month investigation into the origins and legacy of the federal government’s policy of assimilating Native children into white society at government-funded boarding schools.

The 106-page report was the first segment of a comprehensive work plan initiated by Secretary Haaland in June 2021, less than a month after news broke about the discovery of mass graves and the remains of 215 Indigenous children at the Kamloops Industrial Residential School in Canada.

The report contained eight recommendations, including the launch of the “Road to Healing” tour, a series of listening sessions where Indian boarding school survivors and their descendants could talk about their experiences and the ways in which it has affected their families and communities.

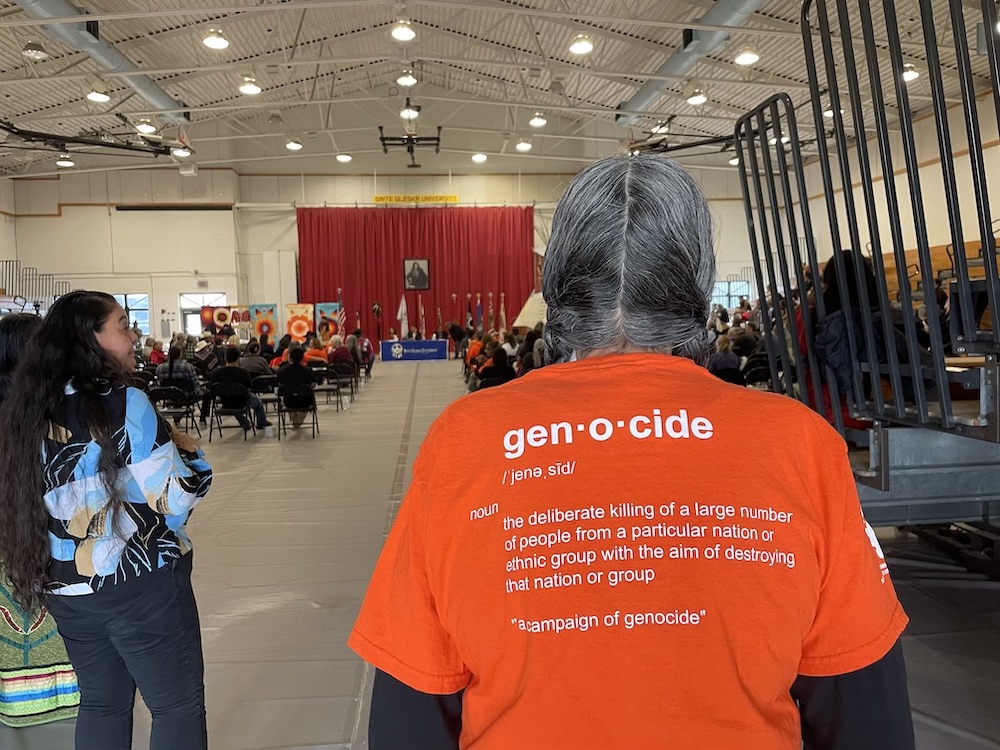

So far, there have been six listening sessions. I have attended five. The sessions are emotional. They are sad. I return home and feel haunted by some of the stories I’ve heard. I am exhausted, but find it hard to sleep.

I’m hardly alone. Last month at Western Michigan University, Assistant Secretary Newland spoke with an audience about how tough it is on Secretary Haaland and him to hear the stories told during the listening sessions.

“People stand up in a gymnasium full of people and talk about the worst things that have happened to them,” Newland said.

Assistant Secretary Indian Affairs Bryan Newland (left) and Native News Online Publisher Levi Rickert (right) at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan on April 13. (Photo: Western Michigan University)

Assistant Secretary Indian Affairs Bryan Newland (left) and Native News Online Publisher Levi Rickert (right) at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan on April 13. (Photo: Western Michigan University)

He recounted one story in particular that demonstrates the generational trauma boarding schools have had on families in Indian Country. A woman in her early 40s stood up and relayed that she had not attended a boarding school, but wanted to talk about her family’s history.

“She worked at an urban Indian health center. She said a letter had come in with somebody trying to find a girl she had gone to boarding school with decades before. And the letter said this girl was my best friend. The letter continued: I always wondered what happened to her. And she said the letter had a picture in it. And she said she opened the picture and her jaw dropped because it was her mom,” Newland recounted.

The woman testified that she never knew her mom went to boarding school. She also talked about her difficult relationship with her mom. She said, “I always had a really bad relationship or a bad relationship with my mom. I thought, I just thought she was mean.”

But in that moment, when she saw the picture, her whole life made sense and her whole relationship with her mom made sense, Newland recounted.

“When you think about that story of that woman, something that happened decades prior to her mom, when her mom was a child, the legacy of that was still affecting their relationship today,” Newland said.

Boarding schools didn’t just affect the survivors, it affected their children and the community, Newland said.

“It affects how you parent. It affects how your kids are raised and their mental health, their physical health,” he continued. “And so these these boarding schools scrambled them all up and put a lot of pain in these relationships. So we still deal with people who never went to the schools, people two generations removed from the schools, (and they) are still dealing in their own lives with the pain that was inflicted at the schools.”

During the five listening sessions I attended, I heard dozens of stories of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse that Native students endured at these boarding schools. People spoke of horrific secrets and evil deeds—beatings and rapes, and even children gone missing to never be seen again. These dark secrets were suppressed for decades because the children were often told that something bad would happen to them if they ever told anyone else.

For all the physical pain endured, it was in some ways less damaging than the mental anguish these children suffered. The whole intention of the schools was to assimilate Native children into mainstream America by “killing the Indian and saving the man.” In the process, Native children were told they were nothing but dirty Indians who did not and would not amount to anything in life. It was a means to not only destroy the Indian inside of them, but cut at the very core of who they were as human beings and destroy their self-esteem.

They were stripped of their Native hair, attire, and language. The end results were the destruction of families, suppression of feelings, and an overwhelming amount of loneliness.

As a journalist and a Potawatomi citizen whose grandmother attended an Indian boarding school, I have felt disturbed to the core of my being by testimony made during the listening sessions. Listening to the survivors talk has been very difficult to hear, but I remind myself that their healing can only happen if we listen. Because listening is a way that we can help carry their burden.

A year has passed since Secretary Haaland and others first spoke the truth about what our government did to Native children and families in this country. It was a painful year where we began to turn these sad truths around. I hope for more truth and more healing for Native families in the coming weeks and months.

Thayék gde nwéndëmen - We are all related.

More Stories Like This

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the YearIndian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Northern Cheyenne Push Back Against Trump Administration’s Effort to Alter Little Bighorn History

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher