- Details

Have you ever wondered why biting into a jalapeño pepper makes your mouth feel like it's on fire, even though there's no actual heat involved? This fascinating phenomenon reveals one of nature's most clever neurological tricks, orchestrated by a compound called capsaicin that literally hijacks your pain receptors.

The Master of Molecular Deception

Capsaicin, the primary compound responsible for the burning sensation in chili peppers, operates through a sophisticated neurological deception. This alkaline, oil-based molecule doesn't actually produce heat or cause tissue damage under normal circumstances. Instead, it manipulates your nervous system's temperature detection mechanisms, creating a false alarm that your brain interprets as dangerous heat.

Much like how online gaming platforms create immersive virtual experiences that feel real to players, capsaicin crafts a convincing illusion of heat through precise molecular interactions. Just as gamers might visit Vulkan Vegas casino for an engaging experience that triggers genuine excitement without real-world consequences, capsaicin provides the sensation of heat without actual thermal damage.

The TRPV1 Receptor: Your Body's Heat Sensor

The key to understanding capsaicin's neurological prank lies in a specialized protein called the TRPV1 receptor, also known as the capsaicin receptor or vanilloid receptor 1. These receptors are primarily found in sensory neurons throughout your mouth, tongue, and digestive tract, where they normally serve as temperature sensors and pain detectors.

TRPV1 receptors function as molecular gatekeepers, typically activated by temperatures above 43°C (109°F) — the threshold where heat becomes potentially harmful. When activated by genuine heat, these receptors change their physical shape to allow calcium and sodium ions to flow through the cell membrane, sending pain signals to your brain as a protective warning.

The Molecular Hijacking Process

When capsaicin encounters TRPV1 receptors, it binds to them from the intracellular side, creating a molecular key-and-lock interaction. The capsaicin molecule adopts a specific "tail-up, head-down" configuration within the receptor's binding pocket, stabilizing the receptor in its open state through hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions.

This binding process triggers the same cascade of events that would occur with actual heat exposure, but without any thermal stimulus present. The receptor undergoes conformational changes that allow cations to flood into the sensory cell, generating the electrical signals that your brain interprets as burning heat.

Your Body's Cooling Response System

Once your brain receives these false heat signals, it immediately activates your body's comprehensive cooling mechanisms. This neurological response demonstrates how thoroughly capsaicin fools your nervous system into believing you're overheating.

The following physiological responses occur when capsaicin activates TRPV1 receptors:

- Increased perspiration to cool the body surface

- Vasodilation of blood vessels to dissipate heat

- Elevated heart rate to improve circulation

- Increased mucus production in the nasal passages

- Tear production to cool and protect the eyes

- Flushed skin as blood vessels dilate

These responses explain why eating extremely spicy food can make you sweat profusely and develop a red, flushed appearance — your body is genuinely trying to cool itself down from perceived overheating.

The Pain-Pleasure Paradox

The neurological effects of capsaicin extend beyond simple temperature deception. When TRPV1 receptors are activated, they trigger the release of substance P and other neuropeptides that signal pain to the brain. In response, your body produces endorphins — natural painkillers that create feelings of euphoria and well-being.

This biochemical process explains why many people develop a tolerance and even a craving for spicy food. The initial pain response is followed by an endorphin rush that can create a mild "high" sensation, making the experience rewarding rather than purely unpleasant.

Individual Variations in Sensitivity

The intensity of capsaicin's effects varies significantly between individuals due to genetic differences in TRPV1 receptor expression and sensitivity. Some people possess fewer capsaicin receptors on their tongues, making them naturally more tolerant to spicy foods. Others have highly sensitive receptors that respond strongly to even small amounts of capsaicin.

Regular consumption of spicy foods can also lead to desensitization, where repeated exposure reduces the sensitivity of TRPV1 receptors. This adaptation mechanism explains why people who frequently eat spicy cuisine can handle much higher levels of capsaicin than occasional consumers.

Scientific Measurement and Understanding

Scientists measure capsaicin potency using the Scoville Heat Unit (SHU) scale, which quantifies the concentration of capsaicinoids in peppers. The following table shows the comparative heat levels of common spicy foods:

|

Food Item |

Scoville Heat Units (SHU) |

Capsaicin Content |

|

Bell Pepper |

0 |

None |

|

Jalapeño |

2,500-8,000 |

Low |

|

Serrano |

10,000-25,000 |

Moderate |

|

Habanero |

100,000-350,000 |

High |

|

Ghost Pepper |

1,000,000+ |

Extreme |

Beyond the Burn: Therapeutic Applications

The neurological mechanisms that make capsaicin feel hot have found important medical applications. Topical capsaicin creams are used to treat chronic pain conditions, including arthritis, neuropathy, and fibromyalgia. The compound's ability to desensitize pain receptors through repeated activation makes it valuable for managing various painful conditions.

Research has also revealed that capsaicin consumption may provide neuroprotective benefits, potentially reducing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases and stroke. These findings suggest that capsaicin's neurological effects extend far beyond creating the sensation of heat.

The Evolution of Spicy Defense

From an evolutionary perspective, capsaicin serves as a chemical defense mechanism for pepper plants. The compound selectively deters mammals while having minimal effect on birds, whose digestive systems help disperse pepper seeds more effectively. This selective neurological targeting demonstrates the sophisticated nature of capsaicin's biological functions.

Understanding why spicy food feels hot reveals the remarkable complexity of our nervous system and how specific molecules can exploit our sensory mechanisms. Capsaicin's neurological prank continues to fascinate scientists and spice enthusiasts alike, proving that sometimes the most intense experiences come from the simplest molecular interactions. The next time you bite into something spicy, remember that you're experiencing one of nature's most elegant deceptions — a chemical compound that convinces your brain you're burning when you're perfectly safe.

More Stories Like This

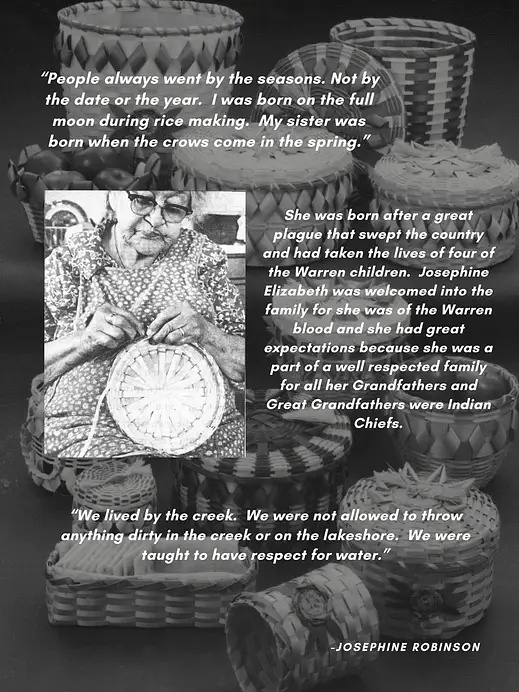

Diné-led nonprofit immerses children in their native languageThe mystery of wildlife and a world beyond our understanding

Feds close to releasing draft environmental review of Colorado River management options

Happy Holidays from Native News Online

After Trump cuts, seeds sit in the warehouse

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher