- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

The Shawnee Tribe is facing significant pushback as it tries to acquire a historic property in Kansas where many of its ancestors were sent — and some were possibly buried — during the Indian boarding school era.

When Shawnee Tribal Chief Ben Barnes walks through three aging, derelict buildings in Fairway, Kansas — what’s left of the former Shawnee Indian Mission Manual Labor School — he thinks of his own family.

“My grandmother's grandfather attended this place and five times he tried to escape in 1850,” Barnes said. “These weren’t preparatory schools getting us ready for academia. These were manual labor academies where folks profited off the labor of young children. The story of what those kids went through is not told.”

Barnes wants that to change. He wants to see the deteriorating former boarding school renovated and restored. He also wants the history of the site to be told more fully and from a Native perspective. That’s why Barnes and the Shawnee Tribe are asking the state of Kansas, which acquired the 12-acre site in 1927, to convey the property to Native ownership.

Chief Ben BarnesThe Shawnee Indian Mission Manual Labor School operated from 1839 to 1862 as part of the federal government’s policy to assimilate Native children. Native children from at least 20 tribal nations attended the school during the boarding school era; some were possibly buried there. Tribal leaders and state archeologists believe there are likely children who attended the boarding school buried in unmarked graves on the school property.

Chief Ben BarnesThe Shawnee Indian Mission Manual Labor School operated from 1839 to 1862 as part of the federal government’s policy to assimilate Native children. Native children from at least 20 tribal nations attended the school during the boarding school era; some were possibly buried there. Tribal leaders and state archeologists believe there are likely children who attended the boarding school buried in unmarked graves on the school property.

Today, the property—now called the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site—is operated as a museum by the City of Fairway and The Kansas Historical Society, which believe “they are the best long-term stewards of such an important site,” according to a statement from the City.

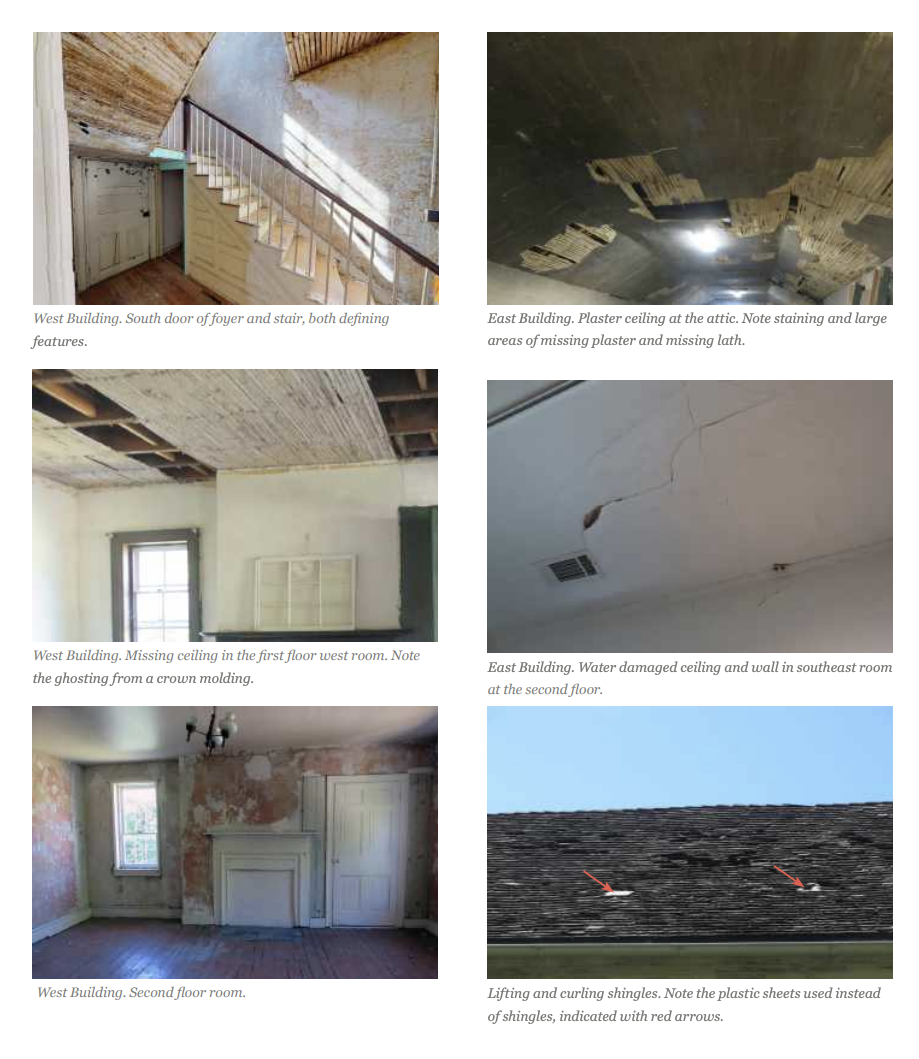

But Chief Barnes contends that holes in the building’s floor, leaking roofs, water damage, and zero truth-telling on the school’s history from an Indigenous perspective say otherwise.

“Their buildings have been inadequately maintained, and the site is endangered,” Barnes told Native News Online. “It’s not just us that say that.”

What experts are saying

An independent architectural assessment as well as correspondence from a national organization dedicated to historic preservation both back Barnes’ claims that significant and immediate repair to the buildings is necessary, as well as updated public interpretations of the boarding school history that center the Native perspective.

“The historic buildings and cultural landscape at the Boarding School have been used to convey various historical narratives to the public since the property became a historic site nearly 100 years ago, including some with little authentic connection to this historic Place,” Rob Nieweg, vice president of National Trust for Historic Preservation—a Washington D.C.-based non-profit dedicated to saving buildings that make up US history—wrote in an email to the Kansas Historical Society last September. “Today, based on information we have received, including comments by the historic site’s curator, we believe the public interpretation of the Boarding School—particularly its impacts on the children and families of Native Americans—is incomplete and out-of-date.”

To get a full accounting of the work needed to repair and maintain the buildings, the Shawnee Tribe in 2021 commissioned an assessment by the Architectural Research Group, an architecture firm specializing in historic structures. The work was done with the support from Kansas Historical Society’s late director, Jennie Chinn.

The report, published to the public in December 2022, concluded that “the three brick buildings…are in need of significant repair and maintenance work, ideally within the next 12 to 18 months.”

The projected costs totaled between roughly $6.6 and $13 million, a sum Barnes said the tribe is prepared to pay.

Images from the architect’s report showing repair work that needs to be done at the Shawnee Mission. (Photos: Architectural Research Group).The report also noted water infiltration issues that, if left unresolved, threaten to jeopardize the historic significance of certain parts of the buildings, including the “highly significant historic space” of the east building’s attic that served as the boy’s dormitory.

Images from the architect’s report showing repair work that needs to be done at the Shawnee Mission. (Photos: Architectural Research Group).The report also noted water infiltration issues that, if left unresolved, threaten to jeopardize the historic significance of certain parts of the buildings, including the “highly significant historic space” of the east building’s attic that served as the boy’s dormitory.

Additionally, last April, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, awarded the Shawnee Tribe $25,000 for their Telling the Full History Preservation Fund. The grant, one of 80 given nationwide, is helping the tribe prepare a forthcoming, more detailed document, a Historic Structure Report— a primary planning document for decision-making about preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, or reconstruction treatments.

What the City and State are saying

But the City of Fairway and the state Historical Society have both chalked the report’s claims up to unsurprising discoveries that amount to “a misinformed conclusion that the buildings are neglected and risk being lost.”

The Kansas Historical Society wrote in a statement provided to Native News Online that, “In general, the report contained no surprises…” and noted that repairs to the three buildings’ roofs were submitted as part of the Historical Society’s five-year capital improvement plan. They also said they made some of the smaller repairs in the year between when the historical society received the report and when it was distributed to the public.

The Shawnee provided the architectural report to the Kansas Historical Society in December 2021 for discussion, according to emails obtained by Native News Online between Chief Barnes and the former historical society director, Jennie Chinn. Barnes and his team met with Chinn about potential solutions for property preservation and maintenance that same month.

One of the solutions was land conveyance, Barnes said. The Shawnee would re-design the space into an interpretative museum that centers around Native experiences at the manual labor school.

But Chinn died suddenly in April 2022, and the historical society’s new interim director, Patrick Zollner, is opposed to giving the property to the Shawnee.

“The Kansas Historical Society has been the steward of this important site since 1927 and has preserved the property at the highest preservation standards as they have evolved over time and will continue to do so in the future,” the Historical Society said in their statement.

Make A Monthly Donation Here

Make A Monthly Donation Here

The City of Fairway also published a public statement in early January opposing the transfer and suggesting that, if the property were conveyed, the Shawnee might instead use the site for “economic development.”

This isn’t the first time the property’s use has been up for debate. In the early 2000s, city leaders proposed building a new Fairway City Hall at the Shawnee Indian Mission site, according to the Kansas City Star.

In a second statement published late last week, the City of Fairway minced the words of another tribe that also has a cultural stake in the property. The City referenced a letter penned by the Kaw Nation’s Chairwoman to Kansas Governor Laura Kelly. The City’s statement selectively edits Chairwoman Kim Jenkin’s letter to undercut the Shawnee Tribe’s efforts, according to Barnes.

Chairwoman Jenkin’s letter notes that the Shawnee Mission sits on aboriginal treaty lands of the Kaw Nation, and says that legislative efforts related to land conveyance “should not be undertaken without consultation with the Kaw Nation.”

“I would ask you to contact me regarding this matter as we are very concerned with the continuation of an effort by other tribal nations and government entities that ignore the historical presence of the Kaw people in Kansas…” she writes.

But the City of Fairway paraphrased her letter to the public to read: “the Kaw state they are ‘very concerned’ that the Shawnee is ignoring the ‘historical presence of the Kaw people in the state of Kansas.’ In addition, they point out that the Shawnee were temporary occupants of land stolen from the Kaw people.”

Chairwoman Jenkins did not respond to multiple requests for comment by Native News Online.

“They’d like to be consulted.”

Barnes takes issue with the claim that the Shawnee are ignoring the Kaw — or any of the other tribes whose ancestors attended the school.

“I think it's clear for anyone that reads that letter that the Kaw is not in opposition to conveyance, they just uphold what they feel (are) their treaty rights and their aboriginal homelands,” Barnes said. “They’d like to be consulted. And from the experience of my tribe and others, we all have had difficulties in getting full consultation from the Kansas State Historical office.”

Just a few months ago, the Shawnee took issue with the Kansas State Historical office when the state agency failed to initiate tribal consultation before approving a roughly $13,000 ground-penetrating radar survey to search for potentially unmarked graves on the property.

Instead of first consulting with the tribes who likely have relatives buried at the site, the state agency finalized a contract with a non-Native geophysical survey practitioner before responding to the Shawnee Nation’s request for consultation.

As a result, the Historical Society has put the work on hold until impacted tribes agree to the work, Zollner told Native News Online this week.

“The only way to tell the truth.”

Without the support of the property owner and manager, Barnes said the Shawnee’s best recourse is to introduce a bill of conveyance in the Kansas legislature, which would allow interested parties—including other impacted tribal nations— to testify.

In a guest commentary in the Kansas City Star this week, the United Methodist bishop for Kansas and Nebraska makes the case that the Shawnee Tribe should guide the future of Indian Mission so Natives can tell their own story.

A bill could be introduced in the 2023 Kansas legislative session that would shift ownership to the Shawnee Tribe, the Rev. David Wilson (Choctaw/Cherokee) writes, adding that previous ownership efforts haven’t succeeded in maintaining the property.

Wilson writes: “It would seem to be in the best interest of the property and of preservation of this structure’s past to place it in the hands of the Shawnee Tribe so the story of what happened there will not fade into history, as have so many of our native people’s customs, languages and cultures.”

Telling the story of what happened to the children at the boarding school from a Native perspective and the proper repatriation of ancestors are important reasons behind the Shawnee’s desire to take ownership of the property, according to Barnes.

“I think we have no choice,” Barnes said. “(We) cannot even begin to search for the bodies of the children that attended this place, because we'd have to have full faith that the current owners would not divulge the location of those buried children. We can't trust other people with the location of these graves. They might leak that information, and (have) some people show up with shovels.”

“So the only way to even begin that search is for us to own the property. The only way to tell the truth of this place is for us to do it.”

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsTrump Veto Stalls Effort to Expand Miccosukee Tribal Lands

Oneida Nation Responds to Discovery Its Subsidiary Was Awarded $6 Million ICE Contracts

SRMT Child Support Enforcement Unit Delivers Holiday Food Boxes to Families

The Shinnecock Nation Fights State of New York Over Signs and Sovereignty

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher