- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

On June 18, the remains of 13-year-old Wade Ayers were set to go home to the Catawba Nation in South Carolina for the first time since he was sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1901. But at the disinterment ceremony, U.S. Army archaeologists excavating under Wade’s headstone found remains inconsistent with those of a 13-year-old boy, which were “instead found to be that of a girl of the approximate age of 15-20.”

Ayers was among the eight Native children who the Army, who controls the grounds at Carlisle, had scheduled to be disinterred and returned to their living relatives this summer. Wade’s relatives have been planning for his return for two decades, they told Native News Online, before the June 18 ceremony.

The girl was reburied under a headstone marked “Unknown.” Office of Army Cemeteries director Renea Yates said in a statement to Native News Online that the Army “is committed to seeking more information in an effort to determine where the remains of Wade Ayres are buried so that he may be returned to his family and the Catawba Nation.”

Tribal leaders say that losing Wade’s remains was not an isolated incident, and that it foretells a grim reality for future Indian boarding-school repatriations across the country.

‘Why don’t they keep track of us?’

In 1879, Carlisle Barracks became the site of the nation’s first government-run Indian boarding school. It was operated by the Department of the Interior until 1918. Under the motto of “kill the Indian, save the man,” it tried to forcibly assimilate 7,800 Native American children from more than 140 tribal nations through a mix of Western-style education and hard labor. At least 186 children died there, of disease often made worse by poor living conditions and abuse.

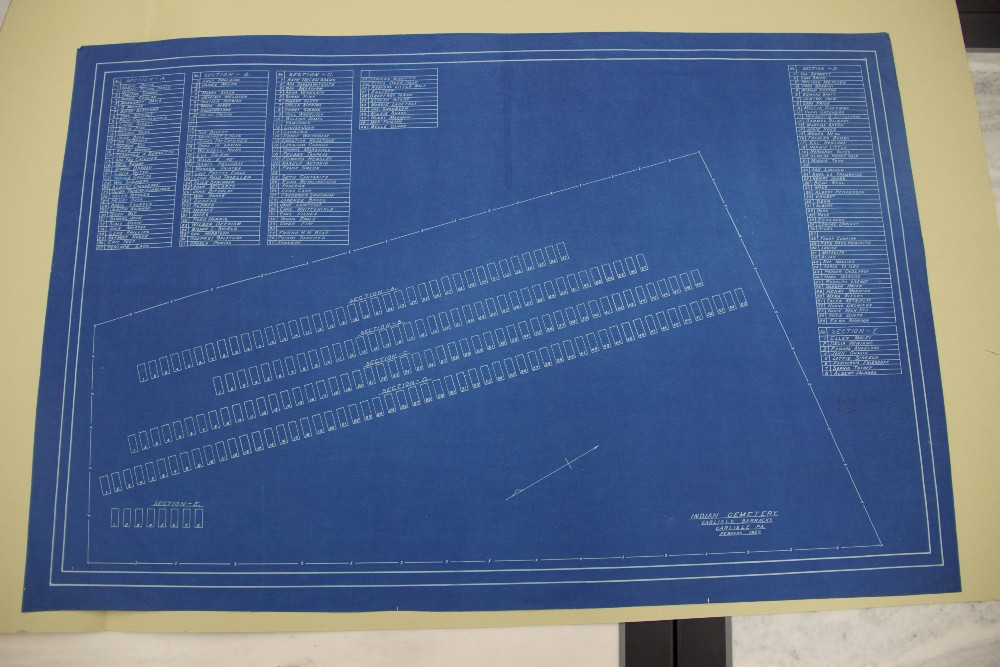

Since 2016, when Yufna Soldier Wolf of the Northern Arapaho Tribe won her 10-year battle to return three Arapaho children who are now reburied on the reservation in Ethete, Wyoming, the Army has returned a total of 23 children. Those disinternments relied heavily on cross-referencing headstone markers with a plot map of the cemetery as it was in 1927—and at least four had irregularities.

In one case, the headstone of one of the Northern Arapaho children had been switched with that of an Apache boy. Soldier Wolf said that error likely occurred when the school moved the cemetery in 1927 to construct a road and new buildings at its old site.

“It's going to be a recurring problem, because it's a secondary cemetery,” she told Native News Online. “They may have started out doing a really good job, but… they were doing it hastily just to finish the job. It’s documented, there's research, but it wasn't really diligently done. That was one thing the tribe was really upset about: Why didn’t they keep track of us? You can go back and find which Civil War soldier was buried where and who they were married to, but when it comes to Native Americans, why don't they keep track of us and the things that we need to know?”

Last summer, two of the nine disinterments of Rosebud Sicangu Oyate youth also yielded surprises: In one of the gravesites, a girl was found buried with body parts from another person. Another girl’s graves also contained the remains of two younger children.

Dr. Michael “Sonny” Trimble of the Army Corps of Engineers, head archaeologist and site manager at Carlisle, said at the time that the mixing of different remains was likely the result of human error and a lack of sophisticated anatomical knowledge when the graves were disinterred and relocated in 1927.

“The simplest explanation is often the best explanation,” he said, noting that he’s seen mixed remains 20 or 30 times in his career. The unidentified bodies and extra bones were reinterred in the cemetery.

Jim Gerencser, archivist of the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, told Native News Online that a lapse in records after the cemetery was moved accounts for a lot of questions.

The map of the original cemetery showed 186 identified graves to be disinterred, while the map for the proposed new cemetery showed space for 192 burials.

(Photo/Courtesy Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center)

(Photo/Courtesy Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center)

“There's a paper trail of some of the planning prior to the move, but I've never seen documentation after the move,” Gerencser said. “It seems like the kind of thing in 1927 that would have been mentioned in a report after the fact, that ‘once we were doing the disinterment, we discovered that there were additional graves that were unaccounted for in the map that was laid out earlier in the year, and so we had to expand the cemetery.’”

He said it's hard to know if records might help identify some of the children, without knowing if such a report was ever written. “Without disinterring each of the plots, it’s very difficult to know for sure.”

‘Where do our spiritual laws have any place in this?’

For Rosebud Sioux tribal historic preservation officer Ione Quigley, who worked with Trimble and his team last summer, dealing with the gravesite anomalies reminded her that dealing with the Army means prioritizing Western ideology over Indigenous traditional knowledge.

When the two additional bodies were found, Quigley called for a stop-work order to consult with a medicine man. He told her that the two children were a boy and a girl who had run away with the older girl, and they all lost their lives.

Quigley told Native News Online that she relayed the information to the Army–that the younger children were the older girl’s “own kind” and therefore needed to complete the journey home with her–but Army policy forbade it.

“I tried to tell the Army, ‘Don't you have a model yourself where you don't leave a companion behind?’ she said. “They just said, ‘well, the law says you can only take [the named one].’ I said, ‘Where do our spiritual laws have any place in this?’”

171 children

At least 171 children still remain buried at the Carlisle Barracks, according to records kept by the Carlisle Indian School’s Digital Research Center. Fourteen of those children rest under headstones marked as “unknown,” after the Army moved the cemetery. That number rose to 15 last week.

Since June 11, two children have been returned to their families, and one is scheduled to be returned on June 23, according to a spokesperson for the Office of Army Cemeteries.

As the number of “unknowns” is likely to rise in the future disinterment of 171 children from Carlisle and more from other former boarding schools, tribes must weigh difficult decisions.

For example, some tribes, including the Northern Arapaho, are opposed to DNA testing that could identify deceased children to be placed with their tribes.

“Once they have our DNA, there's no moratorium, there's no agreement, there's no [memorandum of understanding] with these people to determine what they're going to do with our DNA,” Soldier Wolf said. “We were 100% willing to practice our own sovereignty and exercise [our right] that we don't need DNA analysis to make sure that these children belong to us.”

Soldier Wolf encourages the families still waiting to claim their relatives from Carlisle and other former schools not to give up, even when hope appears to be lost.

She said she had to go back the following year to demand the Army locate her tribe’s third missing child who had been left behind in the headstone mix up. “They weren’t going to, I had to advocate and be like ‘hey, before you start with those other tribes, you better finish the job you started with us.”

“Be assertive,” Soldier Wolf recommended. “Advocate and remember that we all come from strong men and women ancestors who didn't sacrifice their lives for nothing. I'm hoping to go to Carlisle when I'm an old lady and to stand there and not see anything, not even the tree that's there anymore. I want everybody to go home, I want that place to be healed.”

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection RequirementsAmerican Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Northern Cheyenne Push Back Against Trump Administration’s Effort to Alter Little Bighorn History

Florida Man Sentenced for Falsely Selling Imported Jewelry as Pueblo Indian–Made

Navajo Nation Declares State Of Emergency As Winter Storm Threatens Region

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher