- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

After more than a century, the remains of several Native children will be returned home to relatives this summer from the cemetery at the nation’s best-known Indian boarding school.

The U.S. Army, which controls the cemetery at the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Penn., is preparing to return the remains of eight children this summer. Between June 11 and the first week of July, the Army will exhume and return the remains of the Indigenous children to two Alaska Native families and six Native American families, according to a spokesperson from the Office of Army Cemeteries.

Among the ancestors who will be returned is Anastasia Ashouwak, an Alaska Native child who was taken from her home in Alaska’s Aleutian Island chain in 1901 and sent to the Carlisle boarding school on the opposite side of the country.

Ashouwak was taken to an orphanage on Alaska’s Woody Island after her mother died, then escorted by an Indian agent with 10 other children by steamship to Pennsylvania. She entered Carlisle Indian Industrial School as a fourth grader, and died of tuberculosis three years later, a month short of her 16th birthday, according to her records. She was interred at the school under a headstone with her name misspelled as ‘Anastasia Achwack.’

The young girl’s descendants only learned of their ancestor buried at Carlisle when the local museum in Kodiak, Alaska noticed a similar last name in the records of interred children the Army had sent them in the hopes of finding each child’s next of kin.

Anastasia’s great nephew, Ted Ashouwak, 62, will travel with his wife Lara from their home in Maine to Carlisle for the disinterment. Additionally, Ted’s adult daughter, Cassey, and her 13-year-old daughter, will travel to Carlisle from their home in Alaska. Then, the family will make the trip back to Kodiak with Anastasia’s remains for a celebration and a re-burial ceremony.

Ted Ashouwak with his two sons in 2009 at the port of Kodiak island, where Anastasia would have been taken from roughly one hundred years earlier. From left to right: Sam Ashouwak, Ted Ashouwak, Josef Ashouwak (Photo: Courtesy of Lara Ashouwak)

Ted Ashouwak with his two sons in 2009 at the port of Kodiak island, where Anastasia would have been taken from roughly one hundred years earlier. From left to right: Sam Ashouwak, Ted Ashouwak, Josef Ashouwak (Photo: Courtesy of Lara Ashouwak)

Cassey Ashouwak said she had been paying close attention to the news out of Canada about unmarked graves, and was shocked to learn the news about her own family.

“When news came to us that we had a family member (at Carlisle), it just made it more real,” she told Native News Online. “It just made me realize that this little girl who was barely older than my daughter was taken away on a boat and then sent across the country on a train to somewhere absolutely different. Obviously she wasn't able to speak her language or dress. As someone who grew up in a village, being sent across the country had to be terrifying for her.”

Additionally, throughout the process of researching Anastasia, Lara Ashouwak learned of another family member who died at Chemawa boarding school in Oregon: Her husband Ted’s grandmother, who is buried somewhere in Washington state.

“Nobody in the family—none of my husband or his brothers—knew about it,” Lara Ashouwak told Native News Online. “Before, it was such a mystery why (Ted) didn't know about his grandmother. He was part of the story he was seeing on TV, and all of the sudden he looked at it differently. Now they know.”

Lara Ashouwak said she’ll continue her research to locate the grave of her husband’s grandmother after they return Anastasia home.

“I haven’t forgotten,” she said. “One trauma at a time.”

‘We’ll meet him when he gets here’

Since last summer, when the Rosebud Sicangu Youth Council of South Dakota returned nine of their ancestors back home, the Army has taken a proactive approach to returning the remaining Native youth buried in its cemetery.

This will be the Army’s fifth disinterment project at the Carlisle Barracks since 2017, when Yufna Soldier Wolf of the Northern Arapaho Tribe opened the floodgates with her victorious decade-long battle to return three Arapaho children who are now re-buried on the reservation in Ethete, Wyo.

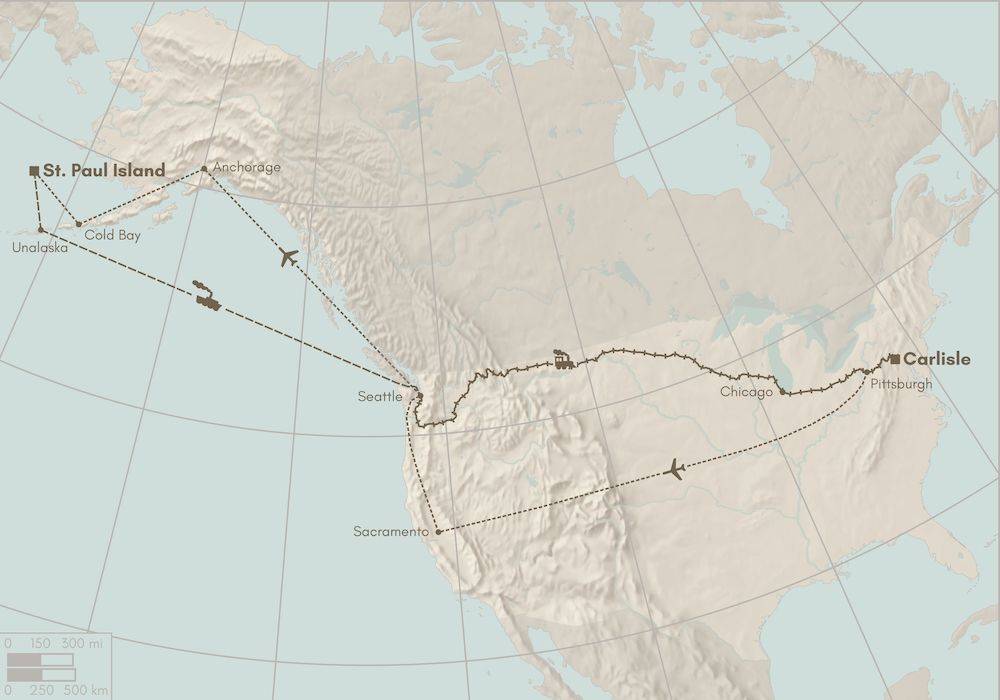

The map photo shows roughly the journey Anastasia and others would have taken from their homes in Alaska all the way across the country to Pennsylvania. Last summer, the Army returned Sophia Tetoff, a young girl who died at Carlisle in 1906, back home to St. Paul Island in the Aleutians. This map roughly depicts Anastasia's similar journey—Kodiak island is located south of Anchorage and east of Cold Bay. (Map: Cartography by Michele Tobias, geospatial data specialist at UC Davis DataLab: Data Science and Informatics).

The map photo shows roughly the journey Anastasia and others would have taken from their homes in Alaska all the way across the country to Pennsylvania. Last summer, the Army returned Sophia Tetoff, a young girl who died at Carlisle in 1906, back home to St. Paul Island in the Aleutians. This map roughly depicts Anastasia's similar journey—Kodiak island is located south of Anchorage and east of Cold Bay. (Map: Cartography by Michele Tobias, geospatial data specialist at UC Davis DataLab: Data Science and Informatics).

The Army has since returned a total of 21 children. At least 173 children still remain buried at the Carlisle Barracks, according to records kept by the Carlisle Indian School Digital Research Center.

The other children returning home from Carlisle this summer: Raleigh James from the Washoe tribe, Wade Ayres from the Catawba tribe, Anna Vereskin from the Alaskan Aleutian islands; Ellen Macy from the Umpqua Tribe, and Frank Green from the Oneida tribe.

Native News Online reached out to each tribe’s historic preservation officer, but only was able to connect with the Washoe Tribe’s Darrel Cruz. He told Native News Online that the tribe will receive the remains of their relative Raleigh James by plane rather than traveling to Carlisle for a disinterment ceremony, due to the age of the James’ descendants.

“We’ll meet him when he gets here,” Cruz said. “Once he does get here, we will return him back to Washoe lands to a designated cemetery. For me, a lot of it is (that) I hold these agencies responsible to live up to their responsibilities. This is one of those cases.”

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

Committee Advances 20% Increase to Navajo Child Support GuidelinesNavajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement Plan

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher