- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

This is the first in a three-part series following the intergenerational effects that the United States government’s century and a half practice of placing Indian children in boarding schools has had on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota. This story was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 Data Fellowship.

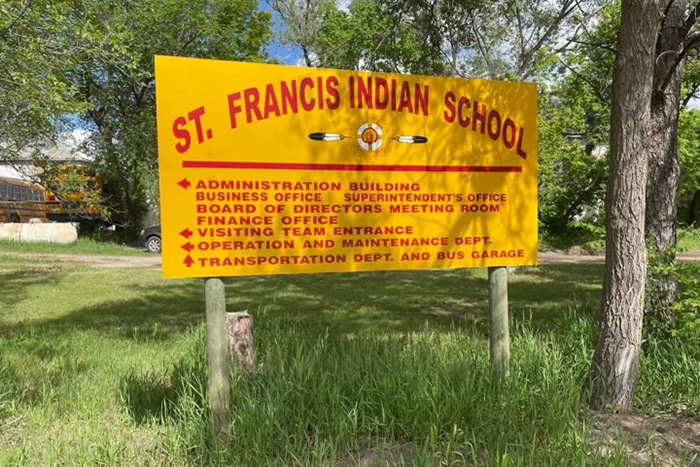

ROSEBUD INDIAN SCHOOL — In the final week of May, the Saint Francis Indian School on the Rosebud Indian Reservation is buzzing with graduation spirit. Children already dressed for summer float a yellow balloon back and forth outside their classroom. Five- and six year-olds march the hallways in traditional ribbon skirts and paper crowns, and one girl wears pink butterfly wings.

In the gym down the hall, Duane Hollow Horn Bear is assembling a small teepee for what’s called an honoring ceremony, a kindergarten graduation. The children in paper crowns will later file towards that teepee, towards Hollow Horn Bear on stage opening the ceremony with a Lakota prayer. They will bounce their knees to the drum beat and wave big circles towards their relatives seated in metal folding chairs. Murals of Native athletes fill the walls.

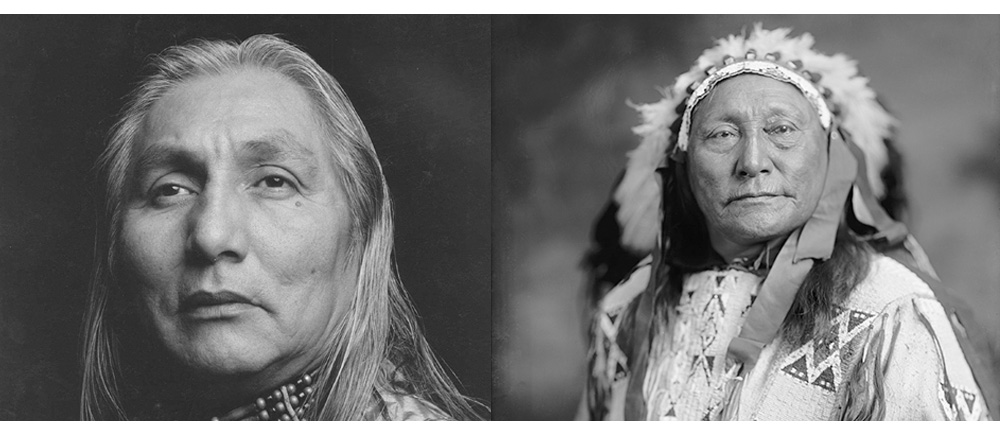

“In the last few days, a generation has finished their education here,” Hollow Horn Bear, 73, a spiritual leader, educator, and survivor of a federal Indian boarding school, told the crowd on May 27.

What he didn’t say: Just three generations before, he had attended the same school, when it was a boarding school called Saint Francis Mission, under control of the United States government and run by the Catholic Church.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, the Rosebud Sicangu Oyate way of life was criminalized in the eyes of the federal government. At Hollow Horn Bear’s kindergarten graduation, there was no traditional dress or language or song. Family members who could afford to travel there had to wait outside until after the ceremony was complete to see their children—the ones who survived.

Hollow Horn Bear also didn’t say this: The United States’ centuries-long policy to eliminate Native culture and take Indigenous land didn’t work, but it left a hell of a mark.

Saint Francis Indian School, previously Saint Francis Indian Mission, is now a tribal government-chartered school funded by the Bureau of Indian Education. The 700 person student body is mostly Native. (Photo/Courtesy)

Saint Francis Indian School, previously Saint Francis Indian Mission, is now a tribal government-chartered school funded by the Bureau of Indian Education. The 700 person student body is mostly Native. (Photo/Courtesy)

The Weaponization of Education

Saint Francis Mission was one of more than 400 Indian boarding schools operated or funded by the federal government through the late 1960s. Half were managed by Christian groups. Saint Francis, opened in 1886, was run by the Catholic Church until the tribe took over in 1972.

By 1926, more than 80 percent of Native school-aged children in America were attending those boarding schools, according to the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. Sickness, abuse, and neglect at the schools was well documented.

It’s unclear how many children died while attending Saint Francis when it was a boarding school, but Rosebud’s tribal historic preservation office is preparing to use ground-penetrating radar in the coming year to look for unmarked graves on the former school grounds.

Nationally, the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report conducted by the Department of the Interior over the course of nine months and published in May 2022 found that at least 500 Native children died at boarding schools across the country. As the investigation continues, Assistant Secretary of the Interior Bryan Newland (Bay Mills Indian Community) estimated that number will rise to the “tens of thousands.”

Beginning with President George Washington, the official policy of the federal government was to forcibly replace the Native culture with white culture under the guise of “education.”

“Indian Education: A National Tragedy—A National Challenge,” a 1969 report by the Senate Special Subcommittee on Indian Education, known as the Kennedy Report after subcommittee chair Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.), describes the rationale behind the practice: “This was considered ‘advisable’ as the cheapest and safest way of subduing the Indians, of providing a safe habitat for the country’s white inhabitants, of helping the whites acquire desirable land, and of changing the Indian’s economy so that he would be content with less land. Education was a weapon by which these goals were to be accomplished.”

“Conditions within Indian schools, particularly boarding schools, have done a great deal to bring about the cause of problem drinking and very little to prevent them,” the report continued. At the time, there were almost 35,000 children in 77 boarding schools. According to the report, academic achievement was a low priority, and many teachers saw their role as “civilizing the native” and believed in “a quite obsolete form of occupational preparation.”

Prioritizing manual labor over basic education left graduates with limited employment options in an industrial economy.

Beginning in 1893, Congress authorized the Secretary of the Interior to withhold rations, including those guaranteed by treaties, to Native families whose children did not attend schools, according to the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report.

“The scariest thing for them is an educated Indian,” Hollow Horn Bear said. “Boarding school never prepared me to succeed in higher education.” He applied to the University of Wisconsin to study—ironically—education, but enlisted in the military in June 1970 after he didn’t get a response from UW.

Hollow Horn Bear looks up at a historic photo of the former Saint Francis Indian Mission school grounds at his office on the present day Saint Francis school grounds. The community is in discussion to change the current school name, he said. (Photo/Jenna Kunze)

Hollow Horn Bear looks up at a historic photo of the former Saint Francis Indian Mission school grounds at his office on the present day Saint Francis school grounds. The community is in discussion to change the current school name, he said. (Photo/Jenna Kunze)

‘They tried so hard to make me hate myself’

Conditions at the schools varied, but corporal punishment was normal at Saint Francis.

Hollow Horn Bear remembers a brutal beating from a scholastic — a priest in training — who searched the boys as they left the dining hall to make sure they didn’t sneak any food out. He was 10 and had taken half his apple to eat later at a movie screening in the gym.

“He whaled on me 50 times for half an apple,” Hollow Horn Bear recalled. “I couldn't be on my back or sit down for days.”

Another Saint Francis survivor, Ione Quigley, told Native News Online that she didn’t even know what violence was until she showed up to Saint Francis as a sixth-grader.

“They tried so hard to make me hate myself, every which way,” said Quigley, now the Rosebud Sioux tribe’s historic preservation officer. Her work includes identifying and bringing home the children who died at boarding schools, which might include Saint Francis.

The nuns and priests “formed a social stratification within the boarding school system,” she said, drawing a pyramid on scrap paper. “The nuns and priests were on top, and then the next layer would be all the non-Natives, like the teachers, (and) the workers. The next layer would be the mixed-blood children, who were English speakers. At the very bottom layer were those of us that were brown and spoke our Native languages.”

Quigley, who was escorted to boarding school from her grandparents’ ranch when police showed up one day, was one of those at the bottom of the pyramid. She recalls the girls receiving beatings from the nuns for events they had no control over: including one who habitually wet her bed, and another time when all the girls in her dormitory accidentally witnessed a nun kissing a priest outside the window.

Although she frequently endured physical and verbal abuse, Quigley said perhaps she was spared from the worst of it since her grandparents spoke English well, and threatened to report the abusive nuns to the diocese after one incident.

“The [students] who had no family or who had no one to stand up for them, I know they were abused,” she said. “Emotional abuse leaves scars on your heart. So does physical abuse—and sexual abuse, I can't even imagine. It takes away your innocence. It takes away your trust, your securities.”

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

In South Dakota alone, former boarding-school students have filed more than 100 lawsuits alleging sexual abuse by clergy members. All 27 Indian boarding schools in the state were run by Christian churches.

“I am a 44-year-old man, and the boarding-school experiences have been locked up inside me all these years,” a classmate of Hollow Horn Bear who was sexually abused by a priest wrote in a 2001 letter responding to a newspaper advertisement seeking information from former boarding-school students. “I know that what was done to me there affected me in a bad way during my whole life, especially in my relationship with my family members, then with my own sons, my wife, my general outlook in life, my relationship with Tunkasila [God], my self-esteem, and the self-medicating during the years when only excessive use of alcohol eased the pain and inner turmoil.”

Exposure to trauma during childhood might dramatically increase people's risk for seven of the ten leading causes of death in the U.S., including high-blood pressure, heart disease, and cancer, according to a massive study conducted in 1995 and 1997 by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In the study, two doctors asked 17,000 mostly white, mostly well-off respondents a set of ten yes/no questions about their history of exposure to what they called “adverse childhood experiences” (ACE), including physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; physical or emotional neglect; parental mental illness; drug or alcohol dependence; incarceration; parental separation or divorce; and domestic violence.

For every yes answer, individuals got a point on their ACE score. By correlating respondents’ answers to their present-day health, research showed that, while more than half of the sampled Americans had at least one such experience, those with four or more were almost eight times more likely to be alcoholics and 12 times more likely to attempt suicide. Children with high ACE scores who did not receive mental-health treatment faced a 20-year decrease in life expectancy.

A study published by the National Institutes of Health in 2003 said that childhood abuse has adverse effects on emotional, behavioral, social, and cognitive functioning as adults. Adults abused as children are more likely to experience depression, aggression, hostility, anger, fear, anxiety disorders, and personality disorders. They are predisposed to addiction, obesity, suicide, and high-risk behavior.

All of the more than 100 people who have filed lawsuits alleging sexual abuse at boarding schools in South Dakota said it had been done by agents of the church, mostly priests and nuns, said attorney Greg Yates, who worked on each of the cases. Some said they simultaneously experienced physical abuse.

All but two of the cases were dismissed by the trial judge before the victims had their day in court. In 2010, South Dakota amended its statute of limitations to prohibit people 40 or older from suing institutions that knew or should have known about sexual abuse. In 2011, the state Supreme Court ruled that complaints of childhood sexual abuse against a church entity had to be filed within one year of turning eighteen.

According to Yates, the only Indian Boarding School sex abuse lawsuit that moved forward was one with “smoking gun” evidence: official letters between Saint Francis Mission officials and Catholic Church higher-ups that explicitly referred to one of the priests, Brother Frank Chapman, “drinking to excess, fooling around with little girls.”

“He has some difficulty with little girls, but I try to be around when they come around after school,” said another letter five years later, in 1973. The officials took no action except counseling him.

Dismissing all those cases, Yates told Native News Online, deprived the survivors of their access to justice “and had the effect of revictimizing these Native American victims of sexual abuse by the clergy.”

At the cemetery in Saint Francis, at least one of the priests named in several lawsuits is buried beside community members, including some of Duane's family members. (Photo/Jenna Kunze)

At the cemetery in Saint Francis, at least one of the priests named in several lawsuits is buried beside community members, including some of Duane's family members. (Photo/Jenna Kunze)

The breakup of family systems

Now in his 70s, Hollow Horn Bear was part of the last generation to attend an institution designed by the U.S. government to strip Natives of their culture and lands, but he’s not the last or the only one to live with the effects caused by the boarding schools.

He entered St. Francis Mission school when he was eight years old and stayed until he graduated, at 20. “Where we are sitting right now, this is where the boys’ playground was,” he said. He points to a row of trees that he planted as a student, and the bark of a taller oak tree where he and his school friends once carved their initials. The old school buildings have since been demolished and rebuilt, and new bark has grown over his markings. But the memories remain.

Perhaps the largest scar that boarding school left on Hollow Horn Bear and the preceding generations came from its separating Native kids from their families, languages, cultures, and traditions for nine months of each year of their entire adolescence. Growing up mostly without his parents and grandparents, he said he didn’t know how to raise children, and eventually neglected his own.

“Boarding school sent a lot of children out into the world without parenting skills,” Hollow Horn Bear said. “Because the time you spend in boarding school, you're away from your parents, your grandparents, where you should have been taught all of those parenting skills. So nobody knew how to be parents. Although they brought children into the world, the knowledge of raising children just wasn’t there.”

According to a University of California at Irvine analysis of data from the 2011-12 National Survey of Children's Health, kids placed in foster care are seven times more likely to experience depression, six times as likely to experience behavioral problems, and two to three times more likely to suffer from learning disabilities, anxiety, behavioral problems, asthma, obesity, and vision problems.

Additionally, a 2006 survey funded by the European Commission’s Daphne Program to examine the risk of harm to children under the age of 3 years living in institutions in 54 countries in Europe and the former Soviet Union, found that being in institutions negatively affects children’s social behavior, interaction with others, and formation of emotional attachments, and was linked to poor cognitive performance and language deficits. In 2009, the United Nations General Assembly issued guidelines saying that no child under 3 should be in institutional care.

The Department of the Interior’s investigation found that some Native children as young as 3 were sent to boarding schools.

Hollow Horn Bear examines the tree on the former grounds of Saint Francis Indian Mission that he and his classmates once carved their initials into as students in 1964. (Photo/Jenna Kunze).

Hollow Horn Bear examines the tree on the former grounds of Saint Francis Indian Mission that he and his classmates once carved their initials into as students in 1964. (Photo/Jenna Kunze).

Culture as medicine

Hollow Horn Bear’s road to healing began with an ultimatum to himself in the summer of 1973. He had returned from the Vietnam War the year before “as a drug addict, alcoholic, lost and angry.” It was the height of the American Indian Movement (AIM), protesting against broken treaties and decades of discriminatory federal policies that led to high unemployment rates and inadequate housing.

He was stationed at Fort Carson, Colorado, when AIM staged a 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee—the site roughly 190 miles west of Rosebud where the Army massacred some 300 Lakota people in 1890—to protest corruption within the Bureau of Indian Affairs and demand the government honor its treaties with Indian country. The National Guard and the FBI were sent to remove AIM occupiers, and a standoff began.

Watching the news on television from Colorado, Hollow Horn Bear felt the friction of one army against another.

“I asked myself: Who the hell am I? I'm a part of this man's army, but they’re pointing weapons at my people. Do I belong to my people, Or do I belong to the army? So I said, ‘I belong to my people,’ and I walked out of Fort Carson.”

Once home in South Dakota, Hollow Horn Bear slowly came to realize that he “wasn’t living right,” and eventually sought the help of Leonard Crow Dog, a renowned Sicangu Oyate Lakota medicine man.

“I thought I found happiness, but it wasn’t true happiness. I was numb[ing] my spirit, numb[ing] my body,” Hollow Horn Bear said. “Then I realized I had to forgive myself, and seek forgiveness of [a] man I didn’t even know whose life I took in Vietnam. And I had to forgive that priest.”

He spent four days and four nights with his pipe, protected by a circle of tobacco ties on a hill in the wilderness.

“The sky turned into an IMAX theater one night, and my life was playing up here. Everything played out: Happy times, sad times, hard times in boarding school. I remembered that priest out there on that hill. I said: ‘Father, I’ve been carrying this all these years. But now, I’m going to forgive you. That day will come where you need to go back to your creator and explain to him why you had to beat this little Indian boy for half an apple. It’s yours; I give it back to you. You’re forgiven.’”

At those words, a total calm came over Hollow Horn Bear as he went through his list of people he “used, abused, and confused” in his lifetime, individually forgiving them all and asking for their forgiveness.

“Life has its challenges, but what really saved me was coming back to my spirituality,” he said.

In Hunkpapa/Oglala Sioux psychiatry professor Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart’s research on historical trauma, which focuses heavily on healing modalities, she found that understanding the trauma and releasing pain by “returning to the sacred path” and the strength of traditional culture will lead to transcending the trauma.

A 2016 study in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine echoed Brave Heart’s finding. It asked 332 people to report their levels of forgiveness, stress, and mental and physical health over a period of five weeks. Those who forgave themselves or another, or asked for forgiveness from a divine power, reported greater psychosocial well-being, less stress, and lower mental distress.

In 2001, Dr. Christina Puchalski, founder and director of the George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health at George Washington University, wrote that scientific evidence suggests that individuals who regularly participate in spiritual worship or who are strongly attuned to their spirituality are healthier and possess greater healing capabilities.

“Ceremonies may help in the healing process, changing brain chemistry, calming traumatic brain,” Brave Heart wrote in a presentation.

For Duane Hollow Horn Bear, that was exactly the right path.

“I’ve forgiven, and I belong,” he said, sitting in his office on the former grounds of Saint Francis Indian School. “Now, I’ve got to provide for these little monkeys in this house.”

This year, he spearheaded the first Lakota immersion school at Saint Francis Indian School. He worked with 14 children from kindergarten to second grade, teaching every subject in Lakota, the language he held onto from growing up with his grandparents, despite the government’s best efforts to erase it. It’s his revenge against the priest in training who beat him, he said.

Now, elementary, middle and high schoolers at the school begin each day with a Lakota prayer, led by Hollow Horn Bear. In his classroom, he breaks down Lakota words for his young students and staff, teaching them about traditional Lakota culture.

“I see my role as giving back to the children what’s rightfully theirs,” he said. “My job is to decolonize them, to teach them our culture.”

When he walks into the immersion classroom, he is immediately surrounded by children reaching for hugs. He individually embraces them all, greeting them in their language.

“We’ve been diminished,” he says later, in English. “But we’re coming back.”

READ: How Indian Boarding Schools have Impacted Generations | Part Two: First Generation Descendants

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsInterior Finalizes Major Alaskan Land Transfer to NANA Regional Corporation

Justice Kavanaugh Freezes Key Voting-Rights Case on Tribal Vote Dilution in North Dakota

Chemehuevi Cemetery of Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indians Added to National Register of Historic Places

Las Vegas Man Indicted for Selling Fraudulent Goods Falsely Claimed as Native American-Made

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher