- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

This is the second in a three-part series following intergenerational impacts the United States’ nearly 200 year policy of Indian boarding schools had, and continues to have, on some tribal members on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota today. This story was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 Data Fellowship.

ROSEBUD INDIAN RESERVATION—In scrolling black ink, LeToy “Toy” Lunderman illustrates intergenerational trauma like this: three big circles represent three generations, the first circle nearly empty but for a sliver of solid—representing all that was taken from survivors of boarding school—and the subsequent circles gradually filling with solid until the last circle is whole again.

She’s the middle circle, the conduit between hardship and healing, among the generation of children born in the mid ‘70s who grew up in the years immediately after the federal government abandoned its Indian Boarding School policy.

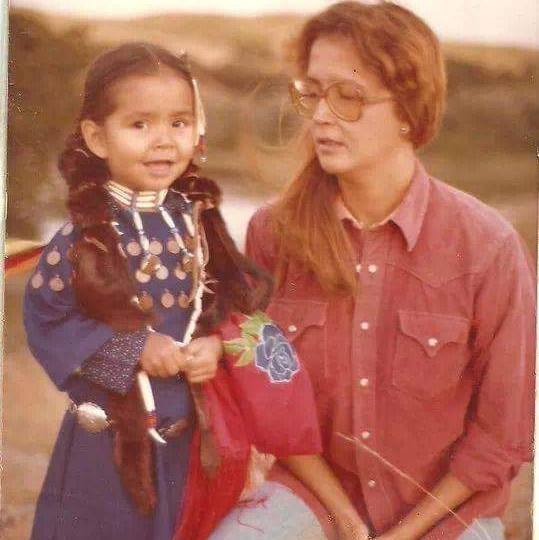

Two year old Toy with her mother, Rosemary Lafferty, whom she always maintained relationship with and became closer to later in her life. (Photo/Courtesy)But it would take her a while to recognize how deeply she’s been impacted by a school system she didn’t directly experience, though she was educated in the same buildings where many in the generations before her experienced abuse: Saint Francis Indian School, formerly Saint Francis Mission, on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Two year old Toy with her mother, Rosemary Lafferty, whom she always maintained relationship with and became closer to later in her life. (Photo/Courtesy)But it would take her a while to recognize how deeply she’s been impacted by a school system she didn’t directly experience, though she was educated in the same buildings where many in the generations before her experienced abuse: Saint Francis Indian School, formerly Saint Francis Mission, on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

When she went to school at Saint Francis, the history of boarding schools–including the abuse that happened there– “wasn’t talked about,” Lunderman told Native News Online, recalling that around sixth grade in 1987 was the first time her school implemented the Indian Education Act that allowed Native culture to be taught in schools. Even then, she says, the extent of the education was grandmas coming in and telling little Lakota stories. “I made no connection between boarding schools and how my family was growing up, which wasn’t very much different than other families—a lot of alcoholism, a lot of violence, unhealthy relationships, poverty. Boarding school created that. But we didn't know that back then.”

At 46, Lunderman’s work now revolves around making those connections, and helping to heal some of the severe trauma inflicted on her community.

Skin Deep

‘Historical trauma’ is a term that came of age alongside Lunderman. First coined in the 1980s by Native American social worker and mental health expert, Maria Yellow Horse Braveheart (Hunkpapa/Oglala Lakota), the term conceptualized historical trauma as the “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding, over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma.”

When historical trauma is not resolved and instead is subsequently internalized, Brave Heart surmised, it begets ‘‘intergenerational trauma,’ which is then passed on to a traumatized person’s descendants—often subconsciously.

In a burgeoning field of study called epigenetics, researchers are connecting historical trauma to altered gene expressions, or the ‘turning off’ or ‘on’ of certain genes based on experiences, that may be passed on through generations.

In some cases, gene alteration can be adaptive, but in others it can be maladaptive and negatively impact a person’s ability to cope with stress. Once those epigenetic changes occur, a person can become more risk-averse, more susceptible to mental illness, and more vulnerable to certain diseases.

At least three prominent studies have tied children of traumatic events that happened before their lifetimes to a modification in the action of genes.

In 2015, a team of researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York studied the genes of 32 Jewish men and women who had survived the Holocaust, as well as 22 of their children born after the war. The study found that Holocaust survivors and their children had that same changes in a stress-related gene, impacting their stress hormones, and possibly making them more vulnerable to stressors.

In 2018, researchers published a study in Science Advances that examined 442 Dutch individuals who were exposed to famine in utero during a 6-month famine at the end of World War II. That research gave a possible explanation why the children of starving mothers tended to be a few pounds heavier on average–from a disruption to the gene responsible for burning the body’s fat.

The following year, researchers surveyed 235 people, a mix of whom were exposed as a fetus to famine in China, and those who were not exposed. The study, published in Scientific Reports, found that those who were exposed had higher waist circumference and drinking rate than those who were not exposed.

Hymie Anisman is a neuroscientist and a professor in Ottawa, Canada, whose work focuses on how psychosocial stressors, such as trauma, relate to the brain.

He’s currently involved in a project with a group, including his former PhD student Amy Bombay from Rainy River First Nation in Ontario, that will be the first of its kind to study the epigenetic impact of Indian residential schools on Indigenous peoples in Canada, where education for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children was modeled after the US boarding school system.

Without that biological data, Anisman said that researchers can only guess at the epigenetic impact to Indigenous People in North America, although studies on children of Holocaust and famine survivors foreshadow what they may find.

“Since the data has not been collected [from an Indigenous population], we don't know what epigenetic changes are there, if any,” Anisman told Native News Online. “I expect there will be. If changes occur as we believe they occur, then there's a high likelihood that epigenetic changes will occur in…Indigenous people as they do with other groups.”

He added that epigenetic changes are often not permanent. “Even if they are embedded, they can be altered by diet and other experiences,” he said. “So you can sort of unring the bell…presumably, if somebody with an epigenetic change was raised in a very good environment with good parenting, good nutrition and so forth, some of these epigenetic changes may be undone.”

State of reality

The Sicangu Lakota Oyate, or Burnt Thigh People–renamed The Rosebud Sioux Tribe by the U.S. government. The tribe was torn from the other six Lakota Nations when the government forced them all onto separate reservations in 1904. They are known as warriors and buffalo-hunters, and were among the last to face off with the U.S. government in the American Indian Wars. Many tribal citizens still carry the last name of prominent chiefs, and ceremony remains a large part of everyday life.

Also part of everyday life on Rosebud are the jarringly high rates of physical and mental health conditions, and cycles of poverty, addiction, and violence.

Todd County, an unincorporated county of South Dakota that lies entirely within the Rosebud Indian Reservation, is the third poorest county in the United States, where more than half the population lives in poverty and a median household income of $22,884, according to 2020 Census data. Unemployment rates on Rosebud are just below 70%, U.S. census records show.

Rosebud tribal members have a life expectancy of about 10 years less than the national average, according to Todd County’s 2021 County Health Ranking. Native Americans across South Dakota face: higher rates of diabetes, asthma, high blood pressure, heart disease, and high cholesterol compared to their white South Dakotan counterparts, according to a 2015 report of the South Dakota Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, in partnership with the South Dakota Department of Health.

In 2007, the Rosebud Sioux Tribal Council President declared a state of emergency due to the number of the suicides. Nationwide, suicide is the second leading cause of death among Native Americans and Alaska Natives between 10 and 34 years old, according to 2019 data from the Office of Minority Health within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

It’s a grim reality that persists, particularly among tribal youth today, Lunderman said. Her 20-year-old son has 11 prayer cards of classmates that have died throughout his schooling. Her 10-year-old daughter has seven prayer cards, representing almost one person lost a year throughout her life.

“It’s hard to not be overwhelmed. But I made a conscious decision to bring my kids back here to raise them in their culture, so that they would know who they are. We have all of that,” Lunderman said, gesturing to the poor health statistics she just rattled off by memory, “but at the same time, when I think about it, [Rosebud] is the most beautiful place in the world.I cannot imagine being anywhere else.”

Indoctrination

Lunderman grew up in the town of He Dog on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. She had a happy childhood surrounded by animals— especially horses—and competed in rodeos around the state. As was common with many boarding school descendants, Lunderman was primarily raised by her grandparents.

Some Native grandparents today are more likely to choose to raise their grandchildren in an effort to stop the cycle of loss initiated by the boarding schools, research from the Native American Rights Fund published in 2019 found.

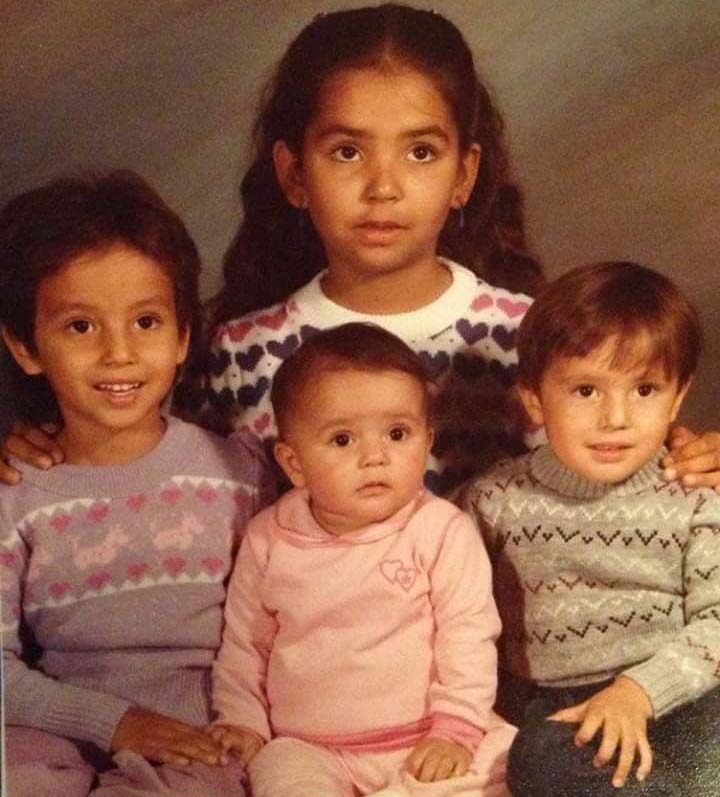

Toy at 8, with the siblings she grew up with. (Photo/Courtesy)“Our grandparents were the first survivors [of boarding school], so their loving wasn't really there, either,” Lunderman said, adding that her grandparents weren’t physically affectionate and never said ‘I love you’ to her or one another. “But I think in the eyes of a lot of our grandparents, they realized they didn't do such a great job with their kids, but they had a chance with us. “

Toy at 8, with the siblings she grew up with. (Photo/Courtesy)“Our grandparents were the first survivors [of boarding school], so their loving wasn't really there, either,” Lunderman said, adding that her grandparents weren’t physically affectionate and never said ‘I love you’ to her or one another. “But I think in the eyes of a lot of our grandparents, they realized they didn't do such a great job with their kids, but they had a chance with us. “

Prerogatives for grandparents raising their grandchildren varies, the report noted: “While some grandparents take on care-giving roles to stop cultural loss, some try to fully immerse their children in Eurocentric ways in order to reduce experiences of marginalization.”

For Lunderman, her experience of her upbringing was largely the latter.

Because Lunderman’s grandparents–particularly her grandmother— had been successfully indoctrinated by the priests and nuns at boarding school to reject their Lakota identities and embrace Catholicism and a “white” way of being, Lunderman remembers growing up feeling like something was missing: her cultural identity.

“We were strict Catholics,” Lunderman said. She re-emphasizes the point. “Strict Catholics. Like, we knelt by the bed and said our nighttime prayers. Christmas and Easter were really big holidays for us.”

Her grandparents were prejudiced against other Natives, and forbade Lunderman and her siblings from playing with “full blood” Native kids or speaking so much as a single Lakota word.

“I mean, they didn't even say ‘Lakota’, they said ‘We don’t talk Indian around here.’ Or they would say, ‘It’s bath time. You’re not going to be a dirty Indian.’” Those are comments like that I grew up with.”

In retrospect, Lunderman can see how the disownment of Indian identity taught in boarding schools seeped into her, as well. As a young adult, she was proud of her middle-class standing, and her separation from the “Indian” part of her.

It wasn’t until she stood at her grandfather’s wake that she learned the man she grew up with not only had spoken Lakota, but that he also had a Lakota name given to him in ceremony. She realized that the fierce rejection of Lakota came from protection, not judgment.

“That's when it clicked, in my own healing,” she said. “That's why they said (Lakota) was such horrible stuff, because in their experience, those that knew, those that spoke, those that practiced were the ones that had the most taken away.”

It was illegal to practice Native American ceremonies and prayer until 1978, when Lunderman was eight years old. Up until that time, Native who were caught practicing their religion.

Prior to this, Lakota elder Duane Hollow Horn Bear told Native News Online, priests would listen outside of the doors of Lakota homes for the sound of drumbeats and ceremony, and withhold government rations from anyone they heard practicing.

Toy's illustration of intergenerational trauma. The top circle represents her grandparent's generation, and the orange represents their culture and all that was taken from them. Toy's mother, the middle circle, began life without much connection to her culture, but gradually re-connected and was able to pass more on to Toy, who is gradually filling up her circle. Her children's circles are nearly full, she imagines, and her grandson's is full.(Photo/Courtesy)Healing by example

Toy's illustration of intergenerational trauma. The top circle represents her grandparent's generation, and the orange represents their culture and all that was taken from them. Toy's mother, the middle circle, began life without much connection to her culture, but gradually re-connected and was able to pass more on to Toy, who is gradually filling up her circle. Her children's circles are nearly full, she imagines, and her grandson's is full.(Photo/Courtesy)Healing by example

Lunderman didn’t get into the healing business intentionally. She simply needed a job and found one at White Buffalo Calf Women's Society, a shelter for victims of violent crimes on Rosebud.

It was 2008, and Lunderman had recently moved back to the rez from out of state to raise her first daughter in their culture. At this point in her life, she had lived through abuse by an intimate partner, deaths of close family members, and substance abuse.

“I can look back and see how there were still aspects—not being able to have healthy relationships, not being able to express your emotions—from the beginning of my life until I had that epiphany, those same skills were being instilled in me.”

At the shelter, Lunderman worked with the project director, her peer, Sunrise BlackBull, to educate tribal members and school children about domestic violence and sexual assault. It was in presenting information about rates of violence of the reservation that the women began asking themselves where such extreme violence originated.

“‘How did we get here? Why do we have these huge rates of violence, and how come we’re so busy at the shelter?’” Lunderman says she remembered asking. “That’s when we started researching the history of violence in Rosebud, and reaching out to [tribal elders like] the Duanes and the Iones. The biggest theme we heard was ‘Well these kids don’t have identity. They don’t know where they come from.’”

Separately, BlackBull, who Lunderman describes as a “research nut,” began coming to work with academic studies she found online that offered a new lens to look at their communities’ experience through.

It started with a TED Talk: The Adverse Childhood Experience Study. In 2018, Nadine Burke Harris, a California-based pediatrician working in the poorest area of San Francisco, had a breakthrough. She began implementing findings from the Adverse Childhood Experience Study, one of the largest investigations of childhood abuse and neglect that connected such experiences to later-life health and well-being.

In the study, two doctors asked 17,000 mostly white, mostly well-off respondents a set of 10 yes/no questions about their history of exposure to what they called “adverse childhood experiences” (ACE), including physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; physical or emotional neglect; parental mental illness; drug or alcohol dependence; incarceration; parental separation or divorce; and domestic violence.

For every yes answer, individuals got a point on their ACE score. By correlating respondents’ answers to their present-day health, research showed that, while more than half of the sampled Americans had at least one such experience, those with four or more were almost eight times more likely to be alcoholics and 12 times more likely to attempt suicide. Children with high ACE scores who did not receive mental-health treatment faced a 20-year decrease in life expectancy.

Lunderman counted up her ACEs: six. Then she counted her daughter’s, and the answer was not good.

“I was like, holy shit. What does that mean?” she remembers. She felt like she was in a movie, being teleported back to look at her life experiences—and her family’s— that led her here.

“I instantly looked at my oldest relatives: the women on my grandma’s side of the family, there's not very many of them that lived past 60. I was like, ‘how many of them have diabetes? Cancer?’”

Another moment of reckoning Lunderman remembers came from a study presented to her by Blackbull, conducted by MIT in 2012 that followed 236 children over a period of five years and found that those exposed to violence early in their life experienced cellular aging at quicker rates than children who did not.

She said that, for the first three years of her daughter’s life, they were in a home with “extreme violence and volatility.”

“It made me realize that I altered my child at that level, and by the time I realized she was 11-years old already. When you’re a mom, it’s hard to imagine yourself not being the best mom. And this [study] was a reality check that I wasn’t.”

“It was like the clouds opened up,” Lunderman remembers. “You could hear the angels singing, because it got me to be able to look at myself in ways that I never knew how to.”

The self-reflection got her to start taking better care of herself, and to slowly begin spreading the work of healing to her community.

The buffer

In the beginning of their work together, Lunderman describes her and BlackBull running around their community like messengers, trying to educate other tribal members about the revolutionary way of conceptualizing their life experiences as collective, rather than isolated. In the years since, she said, the healing work has begun spreading more naturally.

“It’s snowballed in some ways,” Lunderman said. In 2010, on a youth leaders trip back from Washington D.C., a group of teenagers from Rosebud made a last minute stop at the Carlisle Barracks, the grounds of the nation’s first off-reservation boarding school where many Lakota children were sent until it closed in 1918.

On that trip, the youth saw marked graves belonging to nine of their ancestors, and launched a council-backed effort to bring them home in July 2022, six years later. Throughout that process, and especially since their ancestors homecoming last year, Lunderman said, the national attention on boarding schools has inspired more local conversations about the institutions.

In her 40s, Lunderman also began connecting with elders to go to sweat ceremonies, learn her language, and connect with her identity in a way she was never permitted to as a child.

“I think [identity] is such a huge component, because for so many of us that was lost, too. Not only the ability to love or parent, but they took away who we were. They made sure we didn’t remember who we were.”

Slowly, slowly, she can see her circle filling back up again. In her own wholeness, she’s able to be a better parent. Lunderman has made a conscious effort to reduce her youngest daughter's ACE score. By preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences, the Center for Disease Control found, up to 1.9 million heart disease cases and 21 million depression cases could potentially be avoided. That reduction would likely result in savings to Indian Health Services. For example, a 10% reduction in ACEs in North America could equate to an annual medical savings of $56 billion.

Toy and her grandson, Landon Horse Looking, 2 years old. (Photo/Courtesy)“I can't change what happened to my oldest and how she was raised those years, but I made the change where my youngest daughter has never been in a home where there's violence,” Lunderman said. “She's got a sober home. My youngest grew up in her identity. I can see my success, or my growth [as a parent] there.”

Toy and her grandson, Landon Horse Looking, 2 years old. (Photo/Courtesy)“I can't change what happened to my oldest and how she was raised those years, but I made the change where my youngest daughter has never been in a home where there's violence,” Lunderman said. “She's got a sober home. My youngest grew up in her identity. I can see my success, or my growth [as a parent] there.”

She hopes that her healing, and her generation’s healing, has a trickle-down effect.

“My hope is that I can take what I learned—even though it was later in life—and pass it on to my kids to develop healthier habits sooner.”

With her two-year-old grandson who can already beat on a traditional Lakota drum, smudge, and speak Lakota words, she says, maybe the healing will come even sooner.

“[Children today] still need to understand that boarding school impacted them, but [my generation] is trying to be that buffer, so it doesn't hurt so much.”

READ: How Indian Boarding Schools have Impacted Generations | Part One: Survivors

More Stories Like This

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement ActivitiesChickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher