- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

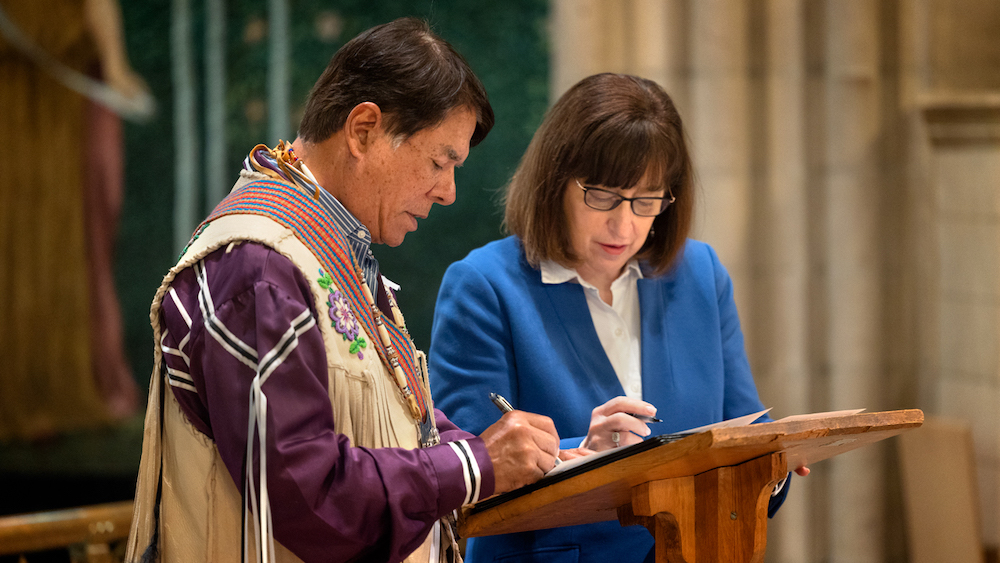

Dean Lyons, an Oneida Nation Turtle Clan member, spoke to three of his ancestors during a transfer ceremony at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, on Feb. 21.

“You will be back in Mother Earth. You will hear the waters again,” Lyons said. “You will hear the animals again. You will hear the thunders again. You will remain here undisturbed amongst your relations.”

After nearly 60 years, university staff returned the human remains of three Oneida ancestors who were dug out of the ground and kept by Cornell’s anthropology department in the campus archive. This week, the ancestors have finally returned home for reburial.

In August of 1964, a property owner digging a waterline ditch in upstate New York’s Broome County, unearthed the human remains of at least three people, according to a Federal Register notice. The property was near the site of Onaquaga, a large multinational settlement on the banks of the Susquehanna River that was occupied by the Oneida people for centuries, according to the tribe. The property owner called the local police, who brought the ancestors to a Cornell anthropologist, professor Kenneth A. R. Kennedy, for identification. When Kennedy died in 2014, the ancestors were transferred to Cornell’s Department of Anthropology, where they have remained ever since, the federal register notice details.

In addition to three ancestors—identified as one “young adult male of Native American ancestry” and two children—Cornell also returned the 22 funerary objects that were unearthed with the individuals.

Although the ancestors came to Cornell more than two decades before the passage of Congressional legislation that requires all institutions and museums receiving federal funds catalog and return all Native American ancestors and belongings in their possession, the university has dragged its feet on returning ancestors for the last 30 years.

Cornell University reported to the federal government in the ‘90s—as required by federal law— that it was in possession of four Native American remains. This year marks the first time it has made any of those ancestors available for repatriation to tribal nations. According to the government’s public database, Cornell still holds one Alaska Native ancestor from Nome, Alaska.

According to Matthew Velasco, an assistant professor of anthropology at Cornell, Matthew, the one individual from Alaska is likely ‘culturally unaffiliated’ — a term that describes a loophole in the federal law. Since 2010, regulations detailed in the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) have provided a process for museums and institutions to return culturally unidentifiable Native American human remains, but the vast majority of museums have chosen not to. Recent proposed changes to the law will swap out “culturally unidentifiable” for “geographically affiliated,” matching the known geographic origins of each set of human remains to a present day tribe.

“To date, no claims have been made to these remains under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act,” Velasco said in a statement to Native News Online. “Nonetheless, the ongoing audit in the Department of Anthropology will be reviewing their provenience to determine if an Alaska Native group(s) with cultural or geographical affiliation can be reasonably identified.”

In 2001, the university returned a totem pole to an Alaska Native corporation, Cape Fox Corporation, according to federal records. The totem pole was gifted to the university in 1899 by the former dean of forestry who was involved in the expedition that removed the totem pole and other objects from Cape Fox Village, Alaska, in 1899.

When an ancestor's remains and cultural artifacts are returned to a tribe, that tribe takes “another step forward in a long journey toward recognition of our sovereignty as a Nation and our dignity as people.,” Oneida Indian Nation Representative, Ray Halbritter, said at the Feb. 21 transfer ceremony in remarks provided to Native News Online.

In November 2022, Colgate University returned 1,520 stolen Oneida funerary objects that were excavated by an amateur archeologist from burial sites within the Oneida Territory in upstate New York between 1924 and 1957. It took 27 years for Colgate to return every Oneida ancestor and burial object it held.

Today, universities and institutions across the country still hold more than 108,000 ancestors, based on their reports. At least 825 of those ancestors and 4,624 of their belongings were removed from burial sites and locations across New York, the federal database shows.

“Some say the repatriation process is too complex, time-consuming and costly. Events like this do not happen overnight,” Halbritter said in his remarks. “Still, universities, museums and other cultural institutions cannot claim these challenges as a reason to avoid doing what is right – what is required in a just society that acknowledges the sovereignty and dignity of Native people and our long fight for this acknowledgment.

“The return of our ancestors to our sacred homelands is a basic human right. It is about our dignity. To delay their repatriation to us – presumably because admitting the wrongs was uncomfortable – is a continuation of the violations.”

Cornell’s Velasco said on Tuesday that, while the university commemorates the return of the ancestors to their homelands, it’s important to ask why they were taken to Cornell to begin with.

“Confronting this painful history is the first step to acknowledge that the pursuit of knowledge and education never again displace respect for the dead, and the rights of their descendants,” Velasco said. “As a biological anthropologist, I am an inheritor of this troubled legacy, and I feel shame acknowledging it.”

On behalf of the Oneida Nation, Halbritter commended Cornell University for finally working with the Oneida Indian Nation to right its historic wrong.

“You are confirming that the complexities of this process are worth solving and that the outcome is worth the time and cost required,” said Halbritter, speaking to university staff. “Yes, it can be uncomfortable. Yet, in taking this major and courageous step today, you are recognizing that the Oneida people are so much more than relics of the past.”

More Stories Like This

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement ActivitiesChickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher