- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

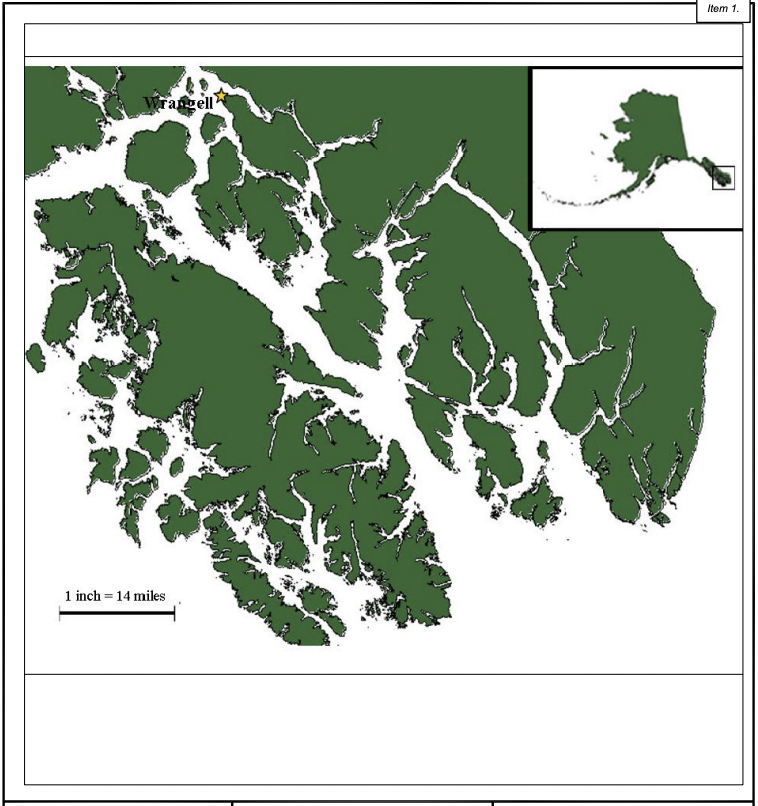

The City and Borough of Wrangell in Southeast Alaska may soon reckon with its Indian boarding school history.

Sometime before spring, the City and Borough of Wrangell intends to conduct archeological surveying over a portion of its property that was once the site of a former boarding school, the Wrangell Institute. That’s according to Wrangell’s economic development director, Carol Rushmore, who said the city needs to conduct the surveying in order to develop on a portion of the former school grounds.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

“Unfortunately, there's a lot of snow on the ground right now, so we don't know when that's going to take place,” Rushmore told Native News Online. “But we’re going to keep moving forward on it so that we know whether we can develop on the site or not. So we're moving forward—I won’t say as quick as we can— but as we can.”

‘High potential to find human remains’

In May, Wrangell applied for a wetlands fill permit to subdivide a portion of the property into single family residential lots. To fulfill the requirements of the federal permit, Wrangell has to prove to the Army Corps of Engineers that there aren’t “cultural resources” that would be disturbed in development.

The State Historic Preservation Office— the state agency providing oversight on the permit otherwise led by the Army Corps of Engineers—recommended ground penetrating radar given “the high potential to find human remains at the Wrangell Institute location.”

Wrangell Institute was a government-run school in the state from 1932-1975 that re-educated Alaska Native students into the dominant western society. Students came from villages across the state that didn’t have schools in their communities.

At Wrangell—much like at other boarding schools across the state and the country—there was widespread sickness and abuse. An unknown number of students died while attending boarding schools, but poor record keeping failed to indicate who the children were, how many passed, and where they were buried.

“Every boarding school had someone pass away in it,” graves protector and sacred site caretaker in Southeast Alaska, Bob Sam (Tlingit), told Native News Online. Sam has spent years researching boarding school histories in and out of the state, and most recently has identified nine of the 14 Alaska Native children buried at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in order to bring their remains home for reburial.

Yet, when he searches for documents on student deaths at Wrangell Institute, he comes up empty.

“I've looked and looked and haven't found any information at all of any (deaths),” Sam said. “I often wonder if it's a cover up. Wrangell Institute has a pretty shady history.”

According to Rushmore, the terrain of the area—forested with thick underbrush— might make it hard for ground penetrating radar or cadaver dogs to effectively locate potential unmarked burial sites.

“We are moving forward with sort of a phase one archaeological survey… as soon as the snow clears,” she said. “From that, we will determine where we will go next.”

Wrangell —formally incorporated as the “City and Borough of Wrangell” in 2008—is in contact with the Department of Interior representative for the State of Alaska, Rushmore said, to consult on records the department might be reviewing in their own national review of unmarked Indian boarding school burial sites throughout the country.

Both the Army Corps of Engineers project leads and Rushmore said the tribal consultation will happen at every level of this proposed work. In May, the Army sent a letter to all 229 tribes in the state informing them of the upcoming survey work and opening themselves up for consultation. According to Army Corps of Engineer tribal liaison, Kendall Campbell, none of the tribes have responded yet.

But the tribal administrator for the local tribe—Wrangell Cooperative Association—Esther Reese (Tlingit) told Native News Online that the tribe will partner with the City and Borough of Wrangell to “play an active role” in any surveying work that takes place.

“We have met with [Wrangell] a couple of times on this and they’re keeping us up to date,” Reese told Native News Online. “We even have plans of doing a memorial there once the search is complete, just to recognize the people that came from all over Alaska.”

Reese said the work has a great impact for her personally.

“My grandfather was shipped off to boarding school in Chemawa, Oregon,” she said. “He definitely suffered trauma there. That trauma sort of worked its way through my family and it’s one of the reasons I'm in my current position, because I would like to play a proactive role in healing that trauma of my people.”

Long Term Healing

Sam, whose mother is a survivor of Wrangell Institute who then refused to send her own kids to boarding school, said this surveying work in Wrangell is just the beginning of reckoning for the state of Alaska.

In Alaska, there were more than 33 boarding schools, each with its own cemetery. The very first, Mt. Edgecumbe boarding school in Sitka, is still open today and run by the Alaska Department of Education and Early Development.

“It’s the tip of the iceberg,” Sam said of the surveying work. “I think Alaska has more bodies than Canada does. I'm hoping that this publicity will identify all of (the schools), and do what it takes to find the bodies.”

In 2022, the Indigenous peoples of Southeast Alaska and their Canadian relatives plan to host their biennial conference in Wrangell to focus on healing from the trauma of boarding schools. “We’ll meet with Wrangell Institute survivors and have a ceremony with them so that they can be free from Wrangell Institute. It seems like Wrangell Institute has a grip on every single one of the survivors.”

More Stories Like This

Committee Advances 20% Increase to Navajo Child Support GuidelinesNavajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement Plan

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher