- Details

- By Andrew Kennard

MAUI, Hawaii — For two decades, Donna Sterling has lived on 12 acres of pastoral land in Kahikinui, a remote and mountainous region of the Hawaiian island of Maui. On her farm and ranch, Sterling grows vegetables, keeps cows and sheep, and leads the local homestead association. Her ancestors, who used to live in the area, are buried on a private plot of land nearby.

“My roots are deep here,” Sterling said.

Even so, Sterling’s land may not remain in her family for more than a generation. Like 9,949 other Native Hawaiian families across Hawaii, Sterling holds the lease to her land under the 1920 Hawaiian Homes Commission Act (HHCA), which reserved approximately 200,000 acres on the islands for Native Hawaiians who have at least 50 percent Hawaiian blood. Families who have obtained leases under the program can pass them on to relatives who have at least one-quarter Hawaiian blood.

While all Sterling’s children would qualify to inherit her land lease under the blood quantum requirements, most — possibly, all — of her grandchildren won’t meet them. If her children pass away without an eligible successor, Sterling’s land will be returned to the state trust rather than passed on to her grandchildren.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

According to a 2020 survey, more than half of the 9,949 Native Hawaiian lessees are in Sterling’s situation. If their children don’t marry Native Hawaiians, these families could lose their homes within two generations. This would go against the wishes of nearly 90 percent of the program’s lessees, who want to pass the land on to their children or other relatives, according to the survey.

“They’re going to start moving away if we don’t guarantee this land is going to be theirs,” Sterling told Native News Online. “They’re going to lose it. So, they’re going to start moving away and not learn all of the cultural (knowledge): the forestry, the water, water diversion, the soil samples, the plants that grow here at this elevation. Then what are we teaching our children?”

In 2017, the Hawaii legislature found that fewer Native Hawaiians have the required blood quantum because of interracial marriages and blended families. It concluded that the inability of Native Hawaiians to inherit a lease unnecessarily displaces them from their land and interferes with their ability to maintain the value of their homes.

For some Native Hawaiian lessees, the problem of not being able to pass down their land is imminent. Nearly half of the lessees are over the age of 65 and more than 10 percent do not have heirs with the required blood quantum, according to the survey. And for Native Hawaiians, a home is more than a financial asset.

“It was the connection to the land that was the basis of the local economy for generations,” said Jeff Gilbreath, the executive director of a Hawaiian Community Assets, a financial services nonprofit focused on helping Native Hawaiians. “It was about having a stable foundation under their feet, where they could visit the family, share their spiritual teachings, their cultural traditions, their mana’o, right? Their knowledge.”

‘What all other Americans take for granted’

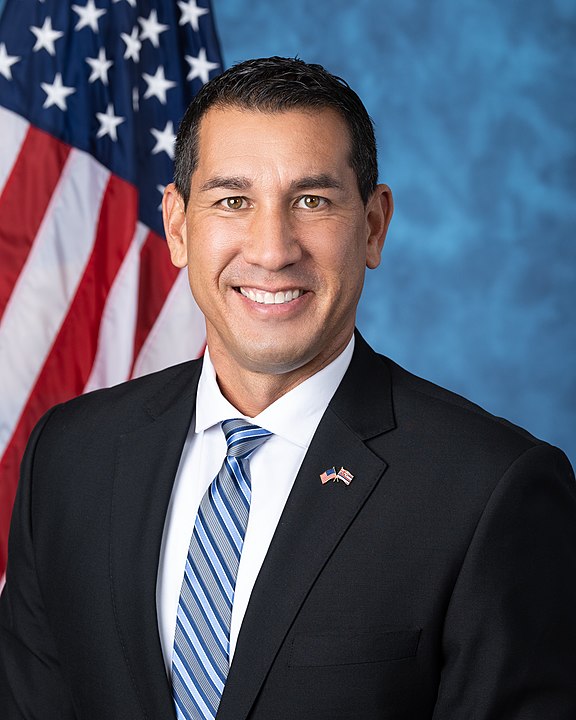

Sterling supports a new bill proposed by U.S. Rep. Kaiali’i Kahele (D-Hawaii) that would allow her grandchildren to inherit her land. Kahele’s federal bill would lower the blood quantum requirement from one quarter to 1/32, or around 3 percent. The legislation is co-sponsored by six Republicans and 10 Democrats, including three American Indian representatives: Tom Cole (R-OK), Markwayne Mullen (R-OK) and Sharice Davids (D-KS).

U.S. Rep Kai Kahele (D-HI)“I think it’s in a great position,” Kahele told Native News Online. “It’s got a lot of bipartisan support, and key members of the Native (American) Caucus … so I think it’s got a great start and has a great chance of getting through this Congress.”

U.S. Rep Kai Kahele (D-HI)“I think it’s in a great position,” Kahele told Native News Online. “It’s got a lot of bipartisan support, and key members of the Native (American) Caucus … so I think it’s got a great start and has a great chance of getting through this Congress.”

Robin Danner, a lessee and the chairwoman of the Sovereign Council of Hawaiian Homestead Associations (SCHHA), said the new bill fulfills an important Native Hawaiian policy goal and would provide “what all other Americans take for granted: the ability to inherit generational wealth.”

The 1/32 requirement was the original vision of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act’s champion, Native Hawaiian prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, a century ago. Kahele introduced his bill, known as the Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole Protecting Family Legacies Act, exactly 100 years to the day after the HHCA was signed into law.

“That was exactly (the prince’s) rationale … that Native Hawaiians would have a permanent land base,” Danner told Native News Online. “That’s also part of the American Dream, of passing on your cultural knowledge, your good ideas about this or that, plus the economic impact of being able to pass on generational wealth.”

‘It’s not a waitlist, it’s a death list’

While the blood quantum requirement keeps some Native Hawaiians from passing their leases to future generations, still more have not received the land they were promised.

Some Native Hawaiians are frustrated to see movement toward changing the blood quantum requirement while they remain stuck waiting for land, according to Patrick Kahawaiolaʻa, president of the Keaukaha Community Association on the island of Hawai’i.

“I haven’t heard this concerted effort from (the waitlist), but I’ve heard people say, ‘What about us?’” Kahawaiolaʻa said.

As of June 30, there were 28,792 Native Hawaiians on the waitlist for land, according to the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands (DHHL), the state agency that manages the land trust. According to DHHL, fewer than 10,000 Native Hawaiians currently hold leases awarded under the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act.

An investigation by ProPublica and the Honolulu Star-Advertiser found that at the rate the department has awarded leases since 1995, it would take nearly 182 years just to get through everyone who is currently on the waitlist. More than 2,000 Native Hawaiians on the waitlist have died without receiving a homestead, according to the investigation.

Robin Danner, Sovereign Council of Hawaiian Homestead Associations “The realities of 2021, the realities of the failure of state government to issue our land — (and) there are available lands like crazy — that is causing death on that waitlist,” Danner said. “It’s not a waitlist, it’s a death list.”

Robin Danner, Sovereign Council of Hawaiian Homestead Associations “The realities of 2021, the realities of the failure of state government to issue our land — (and) there are available lands like crazy — that is causing death on that waitlist,” Danner said. “It’s not a waitlist, it’s a death list.”

The long waitlist is a sore point with Danner and some Native Hawaiians, who say the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands has mismanaged the trust land and funds designated for Native Hawaiians. They take issue with the department for leasing trust land to non-Native Hawaiians to raise money and for not spending more of its funds on developing homesteads for applicants.

“They are a state agency that receives appropriated funds to do a certain job. And that certain job, if they don’t know it, is at crisis levels when you have 28,000 people on a death list,” Danner said of DHHL’s financial management.

DHHL says that it does not receive enough money from the state legislature to meet the demand for land, and a circuit judge agreed in a 2015 decision. However, in June 2020, the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled that the state of Hawaii had “done little to address the ever-lengthening waitlist for lease awards on Hawaiian home lands” over the past 30 years. The court also found that the federal and state governments had mismanaged the trust and had to pay damages to Native Hawaiians for their years on the waitlist.

‘They just stay on the list’

Native Hawaiians also face higher rates of homelessness than the general Hawaiian population, and they live in a state with a high cost of living and the highest median home price in the country. Even if a Native Hawaiian meets the HHCA blood quantum requirements to get a lease, they have to be able to pay the mortgage for the house on the land.

“That right now, in my opinion, is the biggest hindrance to passing (the land) on,” Kahawaiolaʻa said about mortgage payments in Hawaii.

A survey of homeless people in shelters and on the streets of Oahu found that Native Hawaiians were overrepresented by 210 percent, according to Partners in Care, a nonprofit coalition that wants to end Hawaiian homelessness. Oahu is also the island with the greatest demand for homesteads from the waitlist, according to DHHL Director William Aila, Jr.

“I think that the thing in Hawaii is that most people, they don’t qualify (for a lease) income-wise, credit-wise, and so they just stay on the list,” said Kailani Meheula of Kupuna Housed, an organization that is working to raise awareness about Native Hawaiian homelessness on Oahu.

According to a DHHL report on applicants, more than half of waitlist applicants’ first choice for their lease is a turnkey lot: land with a single-family home. However, the report found that 50 percent of applicants are unlikely to qualify for a mortgage for DHHL’s least expensive turnkey lot.

Jeff Gilbreath, Hawaiian Community Assets

Jeff Gilbreath, Hawaiian Community Assets

“Oftentimes, Native Hawaiians we’re working with who are considered ‘houseless’ have jobs, have income,” said Jeff Gilbreath, executive director of Hawaiian Community Assets. “But it’s not enough to afford anything in the private marketplace, which is close to double the cost and price of what’s available on Hawaiian home lands.”

DHHL has moved toward offering more vacant lots where Native Hawaiians can build their own homes, most likely in partnership with a developer or a nonprofit like Honolulu Habitat for Humanity. In 2019, DHHL updated its rules to allow the department to offer multifamily and rental housing, according to its 2020 annual report.

“There’s absolutely need to diversify the product offerings, the sales prices, even do more rental housing,” Gilbreath said. “With housing prices the way they are out here, I think we could benefit from helping Native Hawaiians get out of the private marketplace, get into an affordable rental, and then position themselves for affordable homeownership.”

‘A huge benefit’

Native Hawaiians who do take possession of a lease stand to benefit from the deal offered under the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, namely insignificant land and infrastructure costs and at least seven years free of real property taxes. If Kahele’s bill becomes law, lessees may get to enjoy more of the long-term benefits of homeownership.

According to a 2013 report from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, the “golden rule” of building wealth through a home is keeping ownership over the long run. Gilbreath said passing on a home can potentially help Native Hawaiians send their children to college, start a small business or get through a financial emergency.

“The ability to inherit a home from a parent or a grandparent and bypass the need to come up with a down-payment cost and incur a thirty-year mortgage is just a huge benefit to people,” said Nancy King, a housing program manager and loan specialist for the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement.

Although he thinks DHHL could do better at administering the land trust, the state of Hawaii and also Hawaiian cities and counties need to fund infrastructure and affordable housing for Native Hawaiians, Gilbreath said.

“Again, I’m just going to highlight the need for public dollars to be invested to create equity in Native Hawaiian homeownership in a way that’s just never been done, and has been allowed to not be done,” Gilbreath said.

More Stories Like This

Navajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement PlanNCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher