- Details

- By Levi Rickert

Opinion. Last year, about a week after news broke about the buried remains of 215 innocent school children at the Kamloops Industrial Residential School in Canada’s British Columbia province, I reported on a rally in my hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The crowd of about 200 included many members of our local Native American community. Some proudly carried their tribal flags, one man waved the American Indian Movement flag, and others carried homemade signs. One sign read: “Residential Genocide — 215 Native Children Murdered!”

As the month of June unfolded, more stories emerged from Canada about additional graves that had been discovered at other closed-down residential boarding schools. On the last Saturday of the month, I attended a talking circle, which provided a safe space for the Native community to talk openly about the revelations and share their feelings about the terrible truths associated with Indian boarding schools.

More than a dozen people at the talking circle — mostly young Native women — expressed their hurt and anger over the horrific treatment of Native children at Indian boarding schools. Several wept openly as they talked about what they were feeling and how they were coping with news of Native children who died so far from their familial homes. One woman said the news had caused her to break out with dry heaves.

During the talking circle, it occurred to me that I was witnessing an awakening of a new generation. I realized some may have had a cursory knowledge of Indian boarding schools, but now they were being confronted with a fully formed picture of this horrific and dark chapter of our Indigenous history.

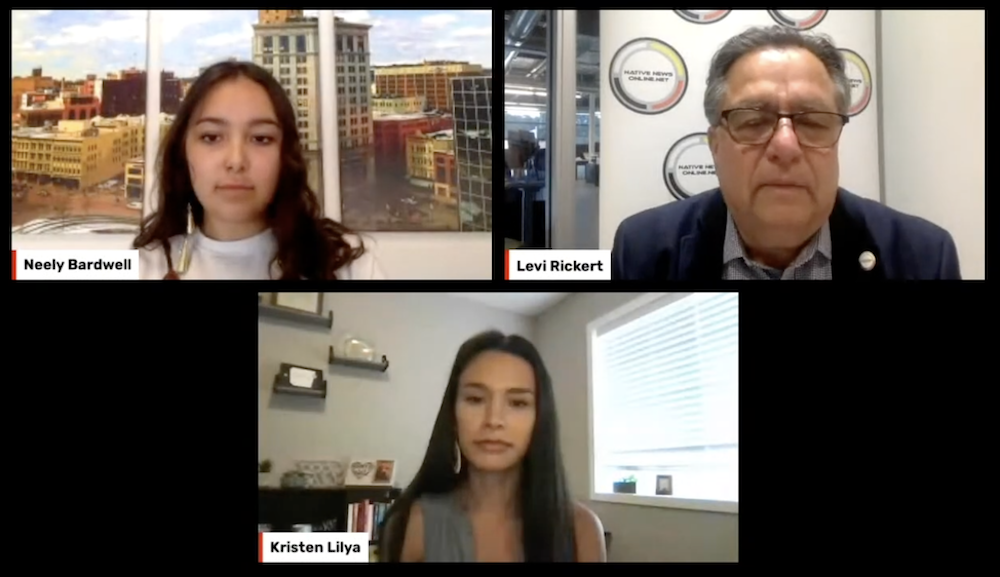

Last month, that picture became more detailed with the release of the Interior Department’s Indian Boarding School report. As our newsroom discussed the report and the intergenerational impact of boarding schools on Native communities, two of the youngest members of our staff joined the conversation. After hearing what they had to say, we decided to interview these two bright young Gen-Z women for our weekly Native Bidaské show to share with our viewers.

Kristen Lilya (Ojibwe) and Neely Bardwell (Odawa) are two young Anishinaabe kwewok (women) who bring a lot of talent and youthful perspective to our Native news organization.

Lilya, a citizen of the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, is a marketing and sponsorship representative for Native News Online’s parent company, Indian Country Media. She also produces our live streams.

Bardwell, a descendant of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indian, began as an intern with Native News Online during the summer of 2021 and is now a freelance writer and policy researcher.

During Friday’s episode, Lilya and Bardwell expressed how heartbroken they were last year when the Kamloops story broke.

For Lilya, who said she learned a little about boarding schools when she was growing up on the Bois Forte Indian Reservation, the Kamloops discovery spurred her to ask her grandmother about their family history with Indian boarding schools.

“I went home and I asked my grandma if she knew anything about Indian boarding schools,” Lilya said. “She told me last year that her brothers and sisters—who were quite a few years older than her—attended boarding schools in South Dakota. They went to Flandreau. But that was a new realization to me because I never knew that before,” Lilya said.

Bardwell recalled growing up in a home where she heard her mother, a former tribal council member, talking about Indian boarding schools. But it was not until her second year at Michigan State University that she heard anything about Indian boarding schools in an educational setting.

So, she knew some of the history of boarding schools before the Kamloops announcement.

“I think that (the Kamloops) discovery was the first time non-Natives finally started to wake up to the boarding school history and the trauma,” Bardwell said. “And I honestly think that that discovery kind of started this bigger movement of (people) finally starting to recognize the trauma and the pain that these boarding schools have caused and continue to cause in our communities.”

Bardwell talked about visiting her grandma this year during spring break and learning something that even her mother didn’t know: that her grandma’s parents had attended Indian boarding schools.

“She shared with me that her parents actually had gone to boarding schools. And so that was new information. And it was very interesting to hear that the boarding school experience isn't as disconnected as we thought,” Bardwell said.

Lilya and Bardwell both spoke about how talking openly about Indian boarding schools is a way to heal.

Bardwell said she knows Native Americans are resilient, but her generation must confront the truths of boarding schools to help the community heal.

“For Gen Z, my generation, we are the future, right? And so for me, that also means a cycle breaker … breaking the cycle of trauma that boarding schools (caused), breaking that cycle of historical and intergenerational trauma,” Bardwell said.

Lilya says it is hard to process all of the lessons of the Indian boarding school system at this point, but she is hopeful that her generation can play a role in helping Native families and communities heal.

“I look at it as a staircase,” Lilya said, “and in my eyes, we're on maybe step two or three and we still have the whole staircase to climb. I hope with our generation — Gen Z — that we can take a few more steps in the right direction.”

WATCH the episode here:

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

Tribal Economic Development Programs in the Federal Contracting Environment: What They Are, and What They Are NotWhy Redefining Public Health Degrees Would Harm Native and Rural Communities

The SAVE America Act Threatens Native Voting Rights — We Must Fight Back

The Presidential Election of 1789

Cherokee Nation: Telling the Full Story During Black History Month

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher