- Details

- By Kelsey Turner

On an October morning in Washington state in 1999, Puyallup tribal member Carolyn DeFord woke up and started to cry. DeFord, then 25, didn’t know why she was crying.

“I cried about everything,” DeFord told Native News Online. “For the red light, for having to get gas, it’s cold outside, I have to go to work.”

When she got to work, however, a coworker shared news that changed her life forever. Her mom’s friend had called – DeFord’s mom, Leona LeClair Kinsey, was missing.

Kinsey lived in La Grande, Ore., about a seven-hour drive from DeFord. Deford, living paycheck to paycheck with three small children, couldn’t afford to leave right away. In the meantime, she filed a missing person report with the La Grande Police Department and had a family member make posters to hang around town. She drove to La Grande as soon as she could, about a week and a half after her mom’s disappearance.

“I remember driving there and thinking – I guess, knowing – that I wasn’t going to see her again,” DeFord said. “I knew that day I was crying, that it was her. I knew when she left, that she prayed for me. That’s what I was feeling that day. And there’s no doubt in my mind that that was her with me. I was grieving her, not knowing that she was gone.”

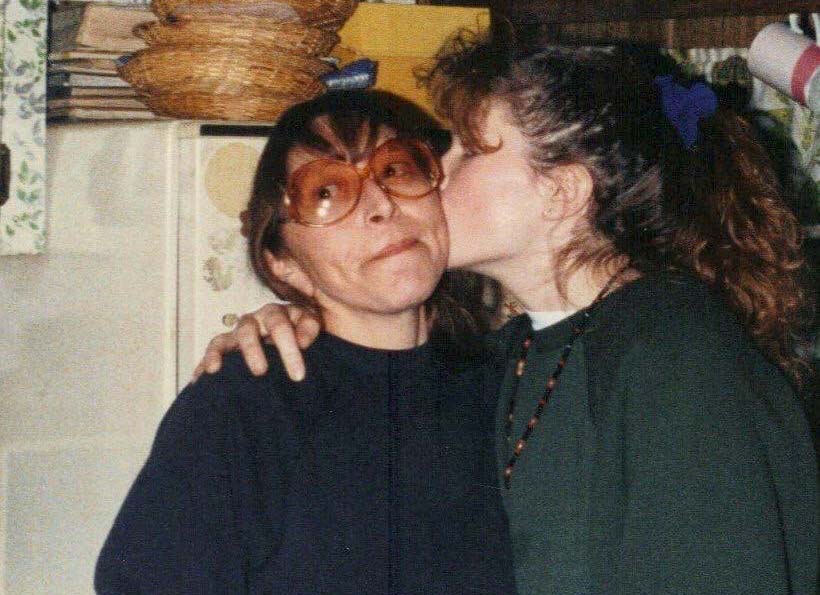

Carolyn DeFord (right) and her mom, Leona LeClair Kinsey, in La Grande, Ore. in 1992. (Photo courtesy of Carolyn DeFord)

Carolyn DeFord (right) and her mom, Leona LeClair Kinsey, in La Grande, Ore. in 1992. (Photo courtesy of Carolyn DeFord)

Several years later, with still no trace of her mom, DeFord went back to the La Grande police seeking answers. Instead, she learned law enforcement had done little to search for Kinsey, she said.

“I was really naive, and thought that the police would do all these things,” DeFord said. “I thought they questioned the neighbors, I thought they fingerprinted her doorknobs, I thought that they did these things.”

She also thought the police had looked for Juan Pena-Llamas, a Mexican man who went by many aliases and who DeFord believes was involved in her mom’s disappearance. Kinsey had planned to meet Pena-Llamas, who she called John, the night she went missing. But when DeFord asked the police about him, the officers told her that, though they had interviewed him, they did not have much information about him.

“It’s a small town, and my mom had a small circle. It wouldn’t have been hard for them to find John in her circle. But I feel like they didn’t try,” DeFord said. “I feel like they dropped the ball in a hundred different places.”

La Grande Police Lt. Jason Hays says he is still working on Kinsey’s case. When Kinsey went missing, the department immediately got her listed as a missing person and started interviewing family and friends, Hays told Native News Online. Pena-Llamas continues to be a person of interest.

Hays said a lack of evidence makes Kinsey’s case especially difficult to solve. “Throughout the course of the last 20 years or so, we’re just not getting any tangible clues or information,” he said. “She just kind of vaporized.”

Another barrier to solving her case is the difficulty of tracking down Pena-Llamas, Hays added. He was arrested for theft in 2006 and subsequently deported to Mexico for being undocumented. “I don’t have the resources to contact anybody in Mexico and find out the status of a citizen down there,” Hays said.

Before being deported, Pena-Llamas had previously been convicted of various crimes, including physical assault, rape in the third degree, and sodomy in the third degree. Hays also said he has reason to believe Pena-Llamas is connected to a Mexican drug cartel, though he cannot verify it. “Everybody that was interviewed who knew him told me he was connected,” he said. “If you hear it from enough places, from a bunch of different people, I don’t have reason to doubt.”

Hays recently posted about Kinsey’s disappearance on the La Grande Police Department Facebook page, asking people to contact the department with information. The post has been shared over 300 times in the past three weeks.

“I want this case to be solved,” Hays said. “I want answers for Carolyn. I have not lost hope. I do what I can. It’s just, we’re not receiving information.”

DeFord added that the Puyallup Tribe has always been supportive of her family. “But most families don’t get that, ever. And if law enforcement isn’t actively working the case, media generally won’t cover it either.”

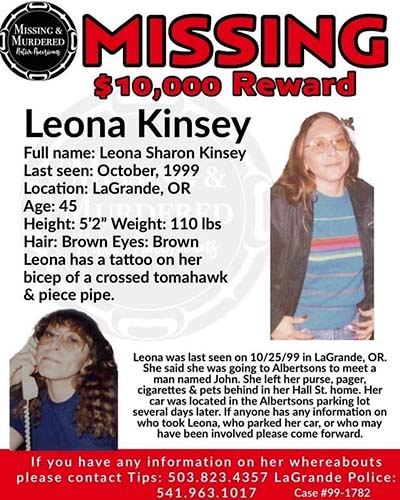

A missing person flyer for Leona LeClair Kinsey, who disappeared from La Grande Ore. over 22 years ago. (Photo courtesy of Carolyn DeFord)The Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Services cold case team has recently begun looking into Kinsey’s disappearance. It took 21 years for them to review the case, DeFord noted.

A missing person flyer for Leona LeClair Kinsey, who disappeared from La Grande Ore. over 22 years ago. (Photo courtesy of Carolyn DeFord)The Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Services cold case team has recently begun looking into Kinsey’s disappearance. It took 21 years for them to review the case, DeFord noted.

DeFord and Kinsey are just two among thousands of Native people affected by the nationwide Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) crisis, an epidemic of violence dating back to colonization.

According to the National Crime Information Center, there were 5,712 reports of missing and murdered American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) women and girls in 2016. Only 116 of these cases were logged in the Department of Justice’s federal missing persons database. A 2018 Urban Indian Health Institute study of 71 U.S. cities found 506 cases of missing and murdered AI/AN women and girls, most from the previous eight years. This is likely an undercount due to limited resources and cities’ poor data collection, the study notes.

In many cases, MMIP family members like DeFord are still not receiving the federal, state, or tribal support they need to find justice for their missing and murdered. But families searching for loved ones do not have time to wait. To support these families, Indigenous survivors across Washington state are leading the work themselves, helping those affected by MMIP to survive, feel heard and, eventually, to heal.

‘It’s still genocide’: A history of disappearance

DeFord is now a member of Washington’s recently created Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People Task Force, which aims to assess causes behind the state’s high MMIP rates. DeFord also serves as Trafficking Project Coordinator for the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, working to educate the community and address human trafficking.

Though a lack of data makes it difficult to know how many MMIP cases are related to trafficking, DeFord said she thinks trafficking and domestic violence play large roles in the disappearances and murders. Indian reservations are the “perfect hunting ground” for traffickers, she said. “Who’s gonna look for you if they don’t have resources?”

More than four in five AI/AN people have experienced violence in their lifetime, including sexual violence, intimate partner violence, and stalking, a 2016 National Institute of Justice study found. These high rates of violence are tied to the nation’s history of genocide against Indigenous people, said Sarah Colleen Sotomish, the Pierce County executive’s senior counsel for Tribal Relations. Sotomish is a citizen of the Quinault Nation and a member of one of Quinault’s five traditional leadership families.

“There’s a lot of history where it was okay to kill Indian men, women, and children,” Sotomish told Native News Online. “And to me, it’s still here today with this problem of missing and murdered Indigenous women. It’s still genocide.”

Disappearance isn’t new – Native people have been made invisible since colonization, Sotomish said.

Sarah Colleen Sotomish, Quinault Nation citizen and Pierce County Executive’s Senior Counsel for Tribal Relations. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Colleen Sotomish)Government-funded Indian boarding schools in the 19th and 20th centuries, for example, stripped Native people of their languages, cultures, and traditions. Some boarding schools are still open today. According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, 73 of those schools remained open as of 2020, and 15 still boarded students.

Sarah Colleen Sotomish, Quinault Nation citizen and Pierce County Executive’s Senior Counsel for Tribal Relations. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Colleen Sotomish)Government-funded Indian boarding schools in the 19th and 20th centuries, for example, stripped Native people of their languages, cultures, and traditions. Some boarding schools are still open today. According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, 73 of those schools remained open as of 2020, and 15 still boarded students.

Assimilation of Native children also continued through other avenues, like the foster-care system. Today, Native families are four times more likely than white families to have their children removed and placed in foster care, according to the National Indian Child Welfare Association.

“That’s a way to make them invisible,” Sotomish said. “Again, that’s a way to strip them of their cultural identity.”

DeFord said the intersections of intergenerational trauma and its effects–including substance use, homelessness, poverty, and the foster-care system–are all risk factors for domestic violence and trafficking. “The things that cause intergenerational trauma are deeply, deeply rooted in our culture, in our country, in colonization. And they’re still happening,” she said. “We’re still carrying this trauma.”

Sotomish remembers a Native middle-school girl she once tutored in Seattle who was adopted by a non-Native family. The girl’s grades were low and she’d begun acting out in school. “I was sitting there thinking, what am I going to do?” Sotomish recalled. “I mean, I can tutor in math and science and things like that. But I realized that wasn’t the problem."

Instead, Sotomish shared literature, pictures, and stories from the girl’s tribe.

“Without spending a lot of time on the curriculum, she started turning her life around, she started getting better grades,” Sotomish said. “And I got that feeling, how many other young girls go through this, or boys? And they’re confused, and they’re conflicted, and they may not like themselves and they don’t have the confidence?”

Sotomish thinks these types of “pipelines” that cause Native children to feel invisible can lead to them experiencing sexual and physical abuse. “Those are some of the ones that these traffickers prey on,” she said.

Disconnection from culture and community can be especially dangerous for Native children who age out of the foster system, Earth-Feather Sovereign, a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes and an Okanogan descendant from Canada, told Native News Online. Sovereign, a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, rape, and domestic violence, is founder and director of the nonprofit Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Washington.

Sovereign noted that many Native people who leave the foster system do not have a place to go. “So a lot of them are on the streets, and this leaves some vulnerable for trafficking and for people to prey on them.” Some Native youth also cope using drugs and alcohol, making them easier prey for domestic violence, sexual assault, and trafficking, she added.

“Sex trafficking has been going on for decades, for generations and generations,” Sovereign said. “Christopher Columbus was one of the first sex traffickers for Indigenous people.”

Centering MMIP families in the fight for justice

Roxanne White, founder of MMIP and Families, human trafficking survivor, MMIP family member, grassroots activist and organizer. (Photo courtesy of Roxanne White)To address this ongoing trauma, Indigenous survivors across Washington work tirelessly to support families affected by MMIP. One of these survivors is Roxanne White, Nimiipuu, Yakama, Nooksack, and Aaniiih.

Roxanne White, founder of MMIP and Families, human trafficking survivor, MMIP family member, grassroots activist and organizer. (Photo courtesy of Roxanne White)To address this ongoing trauma, Indigenous survivors across Washington work tirelessly to support families affected by MMIP. One of these survivors is Roxanne White, Nimiipuu, Yakama, Nooksack, and Aaniiih.

White is the founder of MMIP and Families, a grass-roots organization “centered by families, for families, with families” that is in the process of becoming a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization. An MMIP family member, advocate, activist, and sex-trafficking survivor, White began her grassroots work organizing searches, marches, prayer walks, and vigils, making flyers for the missing, and holding conversations with law enforcement for families that may not feel safe speaking directly to the police.

The most important aspect of her work, she said, is centering families’ voices in the MMIP movement.

“Families are experiencing the most tragic, most horrifying time in their lives,” White told Native News Online. “And there’s this movement that’s occurring all around them. They hear about it, but where are the resources in their reach? For their own needs, for their support? This is exactly why the work needs to be led by families.”

Cheyenne descendant Annita Lucchesi agrees survivors need to be centered in efforts for change. Lucchesi is executive director of the Sovereign Bodies Institute (SBI), an organization that uses Indigenous traditions of data-gathering to create research on violence against Indigenous people. SBI’s MMIWG2 Database uses ongoing consultation with Indigenous communities to log information about missing and murdered relatives.

MMIP and Families missing person flyers bring attention to Destiny Saenz-Santos, an Eastern Shoshone woman who disappeared from Seattle last November, and Mary Ellen Johnson-Davis, who disappeared from the Tulalip Indian Reservation in November 2020. “This is why I do what I do,” White said. (Photos courtesy of Roxanne White)

MMIP and Families missing person flyers bring attention to Destiny Saenz-Santos, an Eastern Shoshone woman who disappeared from Seattle last November, and Mary Ellen Johnson-Davis, who disappeared from the Tulalip Indian Reservation in November 2020. “This is why I do what I do,” White said. (Photos courtesy of Roxanne White)

Lucchesi said her work at SBI is based around the fact that people who have experienced violence know it best. Yet despite this fact, survivors have not historically been involved in MMIP data collection. Lucchesi herself is an MMIP family member, as well as a survivor of trafficking, intimate partner violence, sexual assault, homelessness, and police violence.

In addition to data, SBI offers various services to meet the needs of survivors and families, including a 24/7 crisis-support line that Lucchesi said is constantly busy.

“There’s really no direct services for MMIP families anywhere,” Lucchesi told Native News Online. “A few tribes have started programs, and certainly there’s lots of amazing grass-roots advocates like Roxanne, but there’s no consistent comprehensive system of support. And for most families, there’s no support at all.”

Programs that do exist are often “under-resourced, understaffed, inaccessible, and ineffective,” she added. For the nation’s 574 federally recognized tribes, there are less than 60 tribally created or Native-centered domestic violence shelters.

SBI helps provide necessities to survivors that would otherwise not be available. “Sometimes it’s housing support,” Lucchesi said. “Rental assistance, utility bills, phone bills, car repairs, car insurance, car payments, clothing, groceries, hygiene items, medical bills, emergency transportation to get away from an abuser, bus passes. Pretty much any kind of basic need you can think of, it’s something we’ve covered before.”

One of the biggest issues Lucchesi said she sees in her work is police negligence. “Most of the time, for murder cases, families do know or have an idea of who did it. Sometimes it’s very obvious, sometimes the evidence is there, and the police literally won’t take statements. And even worse, sometimes there’s just a failure to prosecute.”

This is the reason so many MMIP cases occur, she said. “People know they can get away with it. People know that nothing’s going to happen.”

Patti Gosch, tribal liaison for the Washington State Patrol (WSP), said the state’s law enforcement is taking steps to address MMIP. The agency works with families to properly report missing persons and help them understand the investigation process, Gosch said. WSP also publishes a missing persons list, updated monthly, on its website to let people know what the agency is investigating.

“People are being looked for,” Gosch told Native News Online. “There are a lot of dedicated officers that really are looking. But when you’re in crisis and in trauma, it’s never going to be fast enough.”

The federal government has taken steps to address MMIP on a national level as well. In 2021, the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Services launched a Missing and Murdered Unit that investigates MMIP cases and works to connect law enforcement resources across federal agencies. There are now 17 BIA offices throughout the nation that have at least one agent dedicated to solving MMIP cases.

Indigenous activists in Washington are also advocating for legislative change. Several Washington state legislators, such as Tlingit and Aleut Rep. Debra Lekanoff (D-Burlington), are sponsoring bills addressing aspects of the MMIP crisis. House Bill 1725, if enacted, would create a missing Indigenous women and persons alert system that would send missing person alerts to radio and TV stations, social media, and electronic highway signs. The bill passed the House and Senate with bipartisan support and now awaits the governor’s approval.

Another bill awaiting the governor’s signature, House Bill 1571, addresses how the remains of an Indigenous person are handled in Washington. It would require law enforcement and the county coroner, upon knowledge that the remains are of an Indigenous person, to contact family members and tribes immediately, before moving the remains from where they were found. This allows families to visit the remains for spiritual practices or ceremonies.

“I think this step is really important, because I have heard stories with families that say that it was years until their family member was finally returned,” said Earth-Feather Sovereign, who testified for the bill on Feb. 3.

Ceremonial practices and grieving processes are often vital for families to be able to let their loved ones go and put them to rest, Sovereign added. “Our focus is the healing part, and bringing our people home.”

‘Healing is a daily practice’

More than 20 years after Leona LeClair Kinsey’s disappearance, DeFord still has not been able to bring her mom home. But DeFord feels that Kinsey is at peace in the mountains, where her body likely lies.

“When I was little, my mom said that she just wanted to go out into the woods and die, and let the beetles and the bugs and the coyotes feed their families – the circle of life,” DeFord said. “I found comfort in that. That she did get to go out into the woods, and the beetles and the bugs did get to feed their families.”

Even as MMIP advocates like DeFord help other families heal, they are still healing through their own pain as well. Each person’s healing process is unique. DeFord heals by sharing her story with other survivors.

“My story is my sacred item, my one sacred thing that nobody can take away,” she said. “We’re storytellers by nature. When you put it out there, I think it’s its own act of justice.”

Quinault Nation citizen Sotomish, a survivor of childhood and adult violence, finds healing in her connection to her family and tribe. She looks up to her grandmother, a medicine woman who Sotomish described as the “shooting star” she has always been reaching for.

Sarah Colleen Sotomish (right) with her grandmother, Sarah Sam Sotomish, at the Queets Shaker Church in Wash. in 1974. Sarah Colleen is named after her grandmother. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Colleen Sotomish)

Sarah Colleen Sotomish (right) with her grandmother, Sarah Sam Sotomish, at the Queets Shaker Church in Wash. in 1974. Sarah Colleen is named after her grandmother. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Colleen Sotomish)

Sotomish also finds healing in her work giving back to Indian Country. Last October, she launched a Pierce County media campaign to raise MMIW awareness. “Doing what I do is probably as significant of a healing process as I can ever share with you,” she said. “That doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt or I don’t think about it. But I just feel like if I can make a difference in one little way, if I could save one Native woman with this campaign we’re having, I’ve done my job.”

MMIP grass-roots advocate and trafficking survivor White similarly used to view her work as her healing. But White recently hit a point where the weight of this work, which is so personal to her, became too heavy to carry.

“Because of the intensity of trauma, and how heavy it is to do direct services and be directly working with families, the level of healing that I have to do now is not just that,” White said. “I need to work on healing in a whole new transformative way, a way that’s going to bring sustainability for the work ahead.”

One way White is healing is by allowing herself to cry.

“I feel like crying is a ceremony for me. Like it’s a healing ceremony with my own spirit, my body and my mind,” she said. “It’s a prayer that you don’t even have to say anything, because Creator knows what’s in your heart.”

Roxanne White leads her first annual MMIP and Families Prayer Walk on Rainier Ave. South in Seattle, Wash. on May 15, 2021. (Photo courtesy of Roxanne White)

Roxanne White leads her first annual MMIP and Families Prayer Walk on Rainier Ave. South in Seattle, Wash. on May 15, 2021. (Photo courtesy of Roxanne White)

Like White, Lucchesi has found that working directly with MMIP families – though a vital part of her healing process – can be physically and emotionally draining.

“I feel like our kids are being eaten alive by the world,” Lucchesi said. “It’ll mentally kill you if you let it. And the only thing that keeps me from that space is daily victories. Okay, I made sure this kid got fed today. Okay, I made sure this kid had diapers today.”

Lucchesi also finds healing in her sisterhood with other survivors, like White and DeFord.

“Healing is a daily practice, not a destination,” Lucchesi said. “I don’t know that there is a healing where you just feel better one day. You learn to live with it, you learn to carry it.”

Through her work, Lucchesi has seen how current federal, state, and tribal systems are failing MMIP families. But she believes there is one crucial way to do it better: Listen to survivors.

“Get the money in the hands of the people who know how to stretch it and make it work to serve our communities. Give the leadership opportunities to the people who are doing the work,” Lucchesi said. “We have the dedication, we have the commitment, we have the knowledge and the skills, and we have the relationships to do this work right.”

Last winter, DeFord helped a family find their missing daughter. When the family asked how they could repay her, DeFord said they did not owe her anything. “My mom was the kind of person that if she knew somebody was in danger, she would step in and put her life on the line for other people.”

Helping other MMIP families gives her mom’s disappearance a sort of purpose, she said. “It’s doing something. It’s not just sitting there making me feel ugly. It’s allowing me to do something good with it.”

More Stories Like This

This National Cancer Prevention Month, Reduce Your RiskNew Mexico Will Investigate Forced Sterilization of Native American Women

USDA Expands Aid for Lost Farming Revenue Due to 2025 Policies

Two Feathers Native American Family Services Wins 2026 Irvine Leadership Award

Bill Would Give Federal Marshals Authority to Help Tribes Find Missing Children