- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

Esteemed Native leaders, experts, journalists, and those who have worked to repatriate relatives buried at boarding schools, shared their stories in Native News Online’s Monday webinar, Indian Boarding School Discussion: Dealing with the Trauma Today.

The panel was divided into three segments each featuring two speakers: the history of boarding schools in the context of the oppression of Indigneous people; the current discussion around truth and healing; and the ongoing work to bring ancestors buried at boarding schools home.

Help us tell Native stories that get overlooked by other media.

The event was moderated by Native News Online managing editor Valerie Vande Panne and publisher Levi Rickert (Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation). It was supported by the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana, as well as a major sponsorship contribution from global media company Yahoo.

Assistant Secretary of the Interior Bryan Newland (Bay Mills Indian Community) introduced the discussion by highlighting the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative announced by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) in June.

Sparked by the discovery of a mass grave containing 215 Native children at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, the U.S. was forced to reckon with its own ugly past

“Since then, we've been working to identify federal records relating to the operation of these boarding schools with a focus on identifying the sites where they operated, the names and tribal affiliations of students and possible burial sites,” Newland said.

For over a century, Native children were taken from their families and placed in the schools as part of a United States federal government policy to eliminate resistance to the taking of Indian lands, and how to remove further obligations to Indian people. Many children endured emotional, physical, and sexual abuses at the schools, and an unknown number of children died in them. The federal government has never before examined its roll in the genocide of Native children.

While Natives inherently understand the importance of the federal initiative’s work, Newland said that many Americans might wonder why this investigation is important today.

“I think it's crucial that people understand that there isn't a single Native person in the United States whose life hasn't been shaped by the operation of these boarding schools, whether they know it or not,” Newland said. “From the breakup of families to changing family names to the last of our languages and religious practices, to physical and sexual abuse and so much more. These boarding schools have a very long tail that reaches our lives today.”

Where we’re at and how we got here

Speaking to the complex histories of boarding schools were CEO of the National Native American Boarding Schools Healing Coalition (NABS) Christine Diindiisi McCleave (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), and NABS co-founder, author and researcher Denise Lajimodiere (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe).

“Probably the most devastating assimilation strategy and tactic that the United States employed was to take the promise of education-- through the treaties in exchange for all the land--and educate our children in a way that eradicated our language or culture,” McCleave said. “Let's not say we lost our language or lost our culture. We didn't set it down somewhere and forget where it was. It was taken from us and in very brutal, inhumane ways.”

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Lajimodiere, who has been working for over a decade to identify how many boarding schools were (and remain) operational--currently she’s at 408--said the schools have left behind a legacy of something called boarding school syndrome.

“It is PTSD, including recurring intrusive memories, nightmares, flashbacks, detachment disorder, deficient knowledge of traditional culture and cultural skills, trouble sleeping, or anger management, deficient parenting skills, tendency to abuse alcohol and drugs,” she said. “There's also the legacy of adverse childhood experiences which disrupts the brain, leading to higher likelihood of negative health outcomes as adults, including heart disease, obesity, diabetes and autoimmune diseases. We suffer from disproportional cycles of violence, abuse, disappearance, health disparities, substance abuse, premature deaths and undocumented psychological trauma.”

According to Lajimodiere, healing must begin within families first. “I had to forgive my parents for the way I was raised after understanding what happened to them at boarding school,” she said. Further, “Each community individually has to look at what healing looks like for them.”

Reporting personal family histories

Journalists Jenni Monet (Laguna Pueblo) and Sierra Clarke (Odawa/Ojibwe) spoke during the second portion of the livestream, dedicated to each of their personal reporting projects that involve studying their own family histories through the lens of boarding schools.

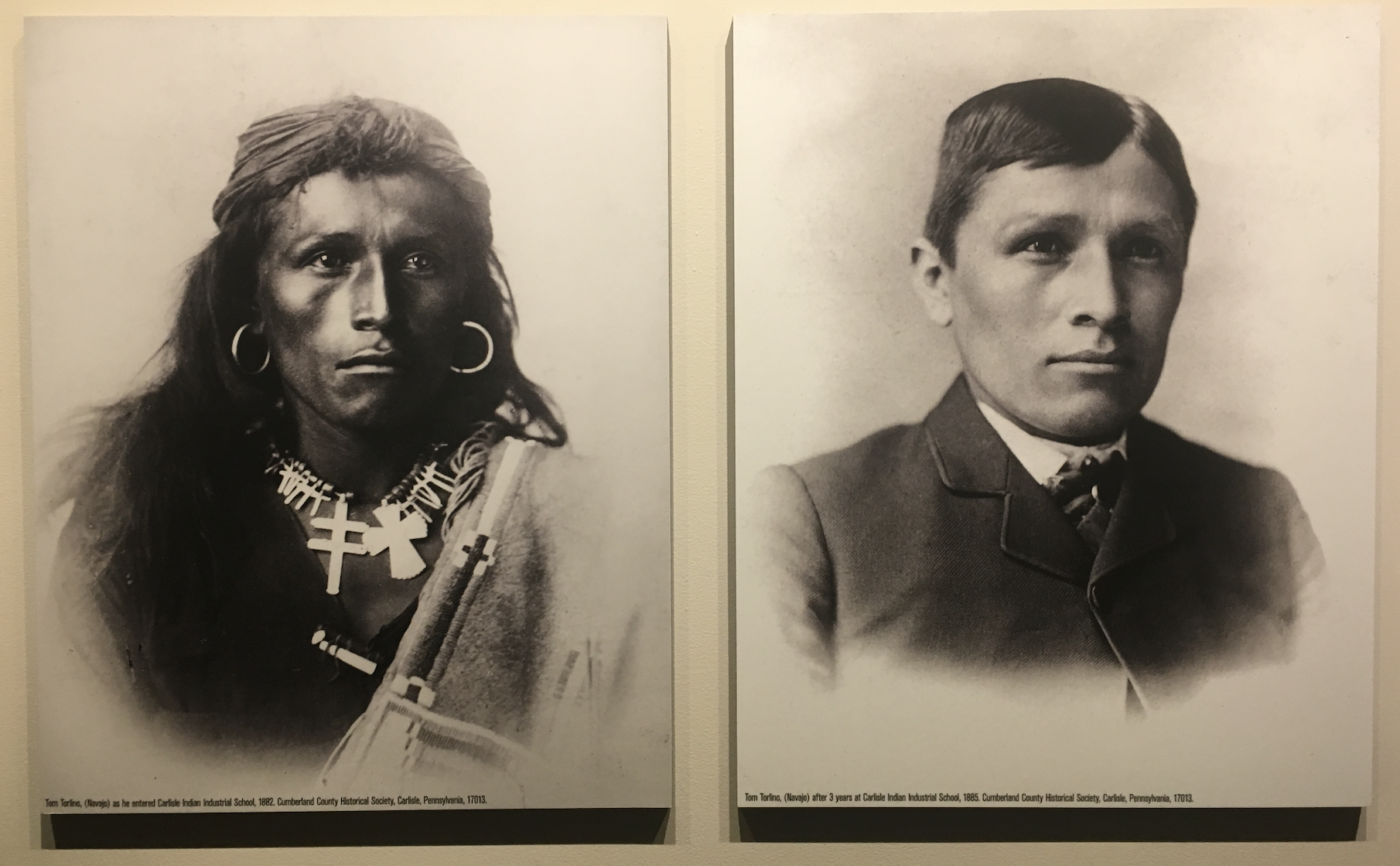

Monet is working to trace her great grandfather’s experience at Carlisle Indian Boarding School and its Outing Program. Outing Programs were set up for students to stay with local families during their summer breaks, under the guise of learning a trade, in an effort to keep them from returning to their culture and languages the school was working to eradicate from them. She is working with a reporting residency program to encourage descendants of Carlisle to reclaim their narrative by sharing it first hand.

Clarke got into reporting on her own family history by accident. Growing up, Clarke said she was devoid of her Odawa traditions and culture.

“While I was looking over records of student names that had attended the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School, I came across my great-grandfather's name and my heart sank,” she said. “There were rumors that swirled around my family throughout my upbringing that we had a relative in a boarding school, but the rumors summed up to just being of something that happened maybe a long time ago. We thought that we just became assimilated into a colonial ...world over the years, and it was far from the truth.”

The magnitude of residential boarding schools is a thread that ties every living Native American together, Clarke said, and the histories of these schools are still alive today through living survivors and generational survivors.

Where we are now and where we’re going

Two tribal members who led their own communities in repatriation efforts for their respective ancestors buried at Carlisle, Youth Council member Christopher Eagle Bear (Sicangu Lakota) and PhD scholar at UC Davis in Native American studies with a designation in human rights Lauren Peters (Agdaagux Tribe) led the final segment of Monday’s webinar.

Eagle Bear was just a teenager when he and other Youth Council members travelling to Washington D.C. stopped at Carlisle Boarding School and asked the question “why are our ancestors buried here?” Six years later, the same youth council, now young adults, traveled back to Carlisle to bring home nine of their ancestors.

“It was very, very eye opening for me,” Eagle Bear said. “Whenever I first started this program, I was very very shy. I didn't know very much about boarding schools and what it meant... and (came) to find out my grandparents were both products of a boarding school here on the Rosewood Indian Reservation. It's something that they never talked about.”

After returning home with their ancestors this past summer, Eagle Bear said he noticed more boarding school survivors were willing to talk about their experiences because they felt like they finally had the space to do so.

“Even my own grandmother started sharing with me some of the things that she went through,” he said. “All I can say is it's very horrific.”

Lauren Peters (Agdaagux Tribe) individually repatriated her great aunt Sophia from Carlisle Boarding School back to her home community St. Paul Island, in the middle of the Bering Sea.

“As for what comes next,” Peters said. “To think about what Denise said about 408 boarding schools... 85% of our people (were) at one time in a boring school, and each one of these boarding schools had their own cemetery full of our children.”

She said bringing children home will help the collective healing.

“We are in the process of finding these lost children,” she said. “And that is a sense of justice. And it's a sense of healing and it is saying that the government can no longer do these things to us. That's a big sense of power that we're bringing back to the community.”

Native News Online will host its second webinar in part of its three part series on Indian Boarding Schools in February 2022. If you missed the webinar, you can watch it here.

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsDeb Haaland Rolls Out Affordability Agenda in Albuquerque

Boys & Girls Clubs and BIE MOU Signing at National Days of Advocacy

National Congress of American Indians Mourns the Passing of Former Executive Director JoAnn K. Chase

Navajo Nation Mourns the Passing of Former Vice President Rex Lee Jim

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher