- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

SAN DIEGO, Calif. — Distance learning is the new normal for students in the age of COVID-19. And for many, clicking into a Zoom class or another online meeting space is as easy as one, two, three.

But for Native Americans living on reservations in San Diego County and throughout the country, simply getting a good enough signal to attend online classes can require an epic effort difficult enough to discourage even the most dedicated students.

This is what Rose and Scott Nunes, who live on the San Ysabel Reservation in northern San Diego County, have rigged up to get their cell phones to work. “[This is] our cell tower," Rose said. "We use this old satellite dish with a cell phone antenna attached to it to sometimes get cell service. This is not a Direct TV service. We use the dish to ‘scoop’ the cell signal and even sometimes connect." (Rose Nunes)“These reservations were put out away from good signals and cell phone service,” said Kumeyaay Community College student Rose Nunes (Santa Ysabel Band of Diegueno Mission Indians). “We’re out here because it’s where the reservation is. It’s frustrating, and it’s hard.”

This is what Rose and Scott Nunes, who live on the San Ysabel Reservation in northern San Diego County, have rigged up to get their cell phones to work. “[This is] our cell tower," Rose said. "We use this old satellite dish with a cell phone antenna attached to it to sometimes get cell service. This is not a Direct TV service. We use the dish to ‘scoop’ the cell signal and even sometimes connect." (Rose Nunes)“These reservations were put out away from good signals and cell phone service,” said Kumeyaay Community College student Rose Nunes (Santa Ysabel Band of Diegueno Mission Indians). “We’re out here because it’s where the reservation is. It’s frustrating, and it’s hard.”

In March, Nunes and her fiancé Scott, who is Mexican-American, were one unit away from completing their Kumeyaay Studies degrees when COVID-19 forced them to take classes from their trailer on the Santa Ysabel Reservation in northern San Diego County. With no decent signal, they drove miles through forest and mountains to a store offering enough bars to suffice, and resumed their studies on the side of the road.

Books balanced on the dashboard, crammed into a three-seat truck with their energetic toddler, the couple struggled to concentrate on the Zoom lessons broadcast through their cell phone.

“We drove there just to get cell phone service,” Nunes said. “It was pretty stressful, especially with a preschooler in the back, bouncing around.”

The Nuneses managed to power through the obstacles, but Rose is worried that due to the internet access issues, “other natives are not going to want to pursue their education. We can totally understand because we were strongly thinking about [pausing, too]. We thought maybe it wasn’t the time or we had to wait.”

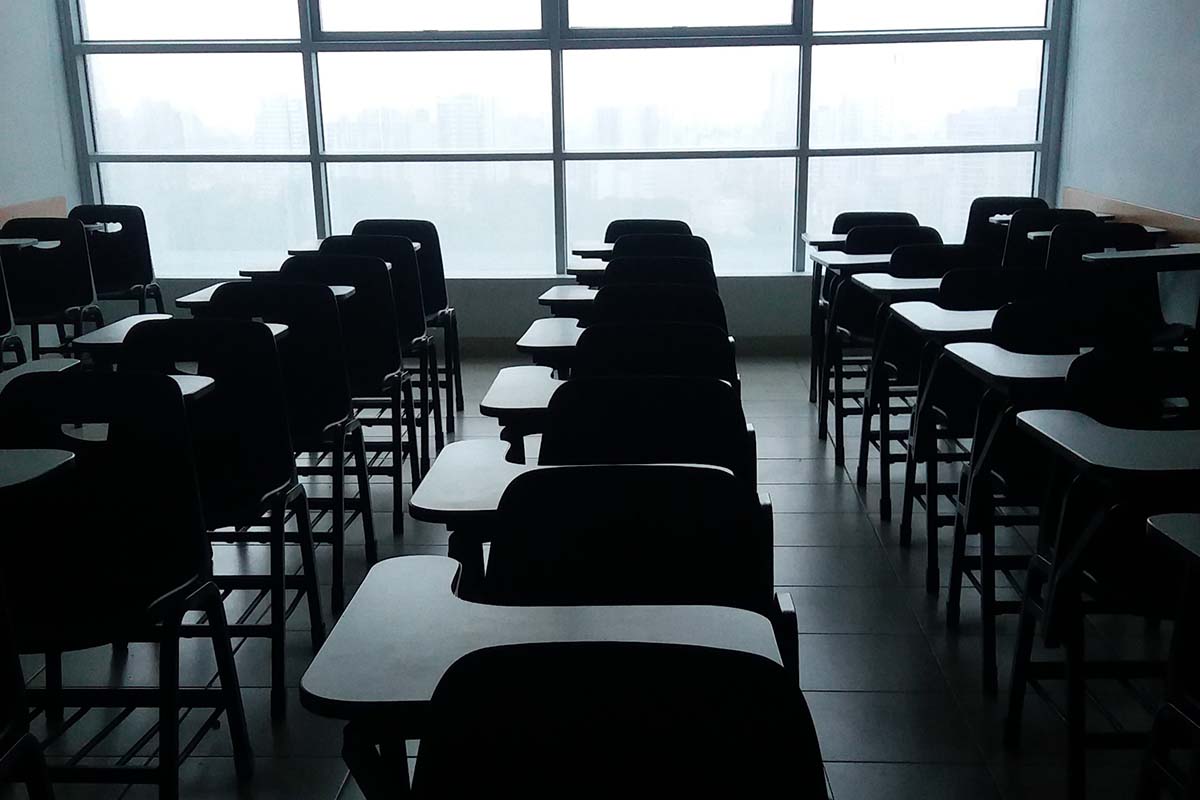

Rose said she noticed classrooms shrinking, as more and more students realized that earning their education from a distance was no longer viable.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey, only 53 percent of Native Americans living on reservations or tribal lands have access to high-speed internet. And even if they do have access, it’s often so spotty it may not even be worth the effort. Like access to healthcare and clean drinking water, this potentially disastrous academic disadvantage is one of the many existing inequities in Indian Country being magnified by the pandemic.

“It’s almost a lost semester, because most of the students don’t have broadband and won’t sign up. I’m really depressed that our people are not going to take these courses just because they don’t have a strong enough internet,” said Kumeyaay Community College history instructor Ethan Banegas (Barona Band of Mission Indians). “It’s going to be a lost year for Native America in education, and imagine what the repercussions will be –– really bad, because we’re already behind.”

The situation in San Diego County is dire, as demonstrated by the recent drop in Native attendance in the Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community College District. Banegas said nearly half of Native American students at Grossmont Community College have either dropped out or suspended their studies.

Kumeyaay Community College history instructor Ethan Banegas (second from left) and his family on the San Diego State University campus. (Ethan Banegas)

Kumeyaay Community College history instructor Ethan Banegas (second from left) and his family on the San Diego State University campus. (Ethan Banegas)

Benegas’ students at Kumeyaay Community College, which has a partnership with Cuyamaca Community College, are following the same sad pattern.

“All my courses went to Zoom immediately in mid-March and almost none of my Native students can do it. They would get dropped from the internet, it would freeze,” Banegas said. “They cannot do it. It doesn’t work. I would only have non-Native students and maybe one Native. It just shows the disparity.”

Banegas interviewed students on several Kumeyaay reservations about the quality of their service. Some said the internet doesn’t work when it gets dark, and others have told him they have to turn off everything else in the house to get the Wi-Fi to work at all.

“We've got a Third World internet,” Banegas said. “It’s like living in a city 10 or 20 years ago.”

Efforts have been made to increase and improve access during the pandemic, but those measures aren’t solving the underlying issues.

Part of the funds designated to the CARES Act went to Native schools. That money allowed San Diego County’s Cuyamaca College, which partners with Kumeyaay Community College, to distribute Chromebooks and mobile hotspots to Native students.

“So they tried to give hotspots to Natives, but the hotspots don’t matter if the towers aren’t there,” Banegas said.

The Nuneses were very hopeful about the hotspots, until they tried to use them.

“No disrespect about it, and not that I'm ungrateful, but I just felt like they weren't thinking of us. I was just so excited to be disappointed that the hotspots didn’t work out here,” Rose said. “We tried [to make them work] with our booster, and then I felt let down.”

Zooming ahead

Before the COVID-19 shock hit the country, the Kumeyaay community was adapting nicely to distance learning via satellite campuses on reservations. The Kumeyaay reservations are scattered throughout San Diego County, far from most college campuses, and students were already virtually attending classes before the pandemic.

The San Pasqual Reservation (Kumeyaay) in San Diego County has a satellite Kumeyaay Community College campus, where students living on the reservation attend virtual classes. (Krystopher Chaipos)

The San Pasqual Reservation (Kumeyaay) in San Diego County has a satellite Kumeyaay Community College campus, where students living on the reservation attend virtual classes. (Krystopher Chaipos)

Kumeyaay Community College itself is located on the Sycuan Reservation, and Banegas said he can teach there and beam to the satellite campuses on the San Pasqual and Campo reservations simultaneously. The satellite campuses opened in 2018, and another will soon be created on the Santa Ysabel Reservation, where the Nuneses live.

“We were ahead of the game before COVID-19. We were already doing it,” Banegas said. “But what we found during the pandemic is, you can’t go to the classroom because of social distancing, so everyone now has to take the courses at home.”

The satellite classrooms get good internet signals, but the reservations are vast and oftentimes a reliable connection can’t be found everywhere.

“With reservations, houses are spread out all over the place, on mountainsides, in crevices, in valleys… you can’t lay fiber optic cable on that land,” Banegas said. “You have a challenging scenario to begin with.”

Before the satellite campuses shut down, the Nuneses would drive 15 miles to the San Pasqual reservation to take their classes. There, they could benefit from Banegas’s classes and learn from instructors who visit the satellite classrooms to teach in person. They also enrolled their son at the San Pasqual Reservation preschool, so both parents and child could focus on their studies without distraction.

“We were Zooming our classes early on. It worked perfectly. We were happy to travel,” Scott Nunes said. “We also used the library and San Pasqual education center for access, printers and computers. But all that went away as soon as COVID-19 hit. We lost our capacity to print and use a computer terminal. We were down to our phones.”

The cell phone reception at their home on the reservation wasn’t strong or reliable enough to attend their classes, so they were forced to drive miles away from home to a place with a workable signal.

Even though they were ultimately able to connect, they know the quality of their learning suffered as a result of their uncomfortable and complicated situation.

“We were taking ethnobotany at the time. We want to learn as much as we can to make [good] use of the environment,” Scott said. “There was clearly a compromise in our level of retention when it came to the science classes.”

The Nuneses, both of whom already have degrees in different subjects, want to make it clear that they are thankful for the opportunity to get an education, and that they appreciate everything the reservation provides for them.

They also say they recognize the challenges of getting good internet service in an environment most people can’t begin to understand.

“It is difficult to try to break down to somebody who has never experienced it, when you start talking about Bureau of Indian Affairs roads and addresses, or service providers not wanting to come out here, or a waiting list [for internet service],” Scott said. “It’s difficult to envision.”

The digital divide

Kumeyaay Community College. Photo from Yelp.Cuyamaca and Kumeyaay Community College will resume online classes in the fall, and no one knows when social distance learning will come to an end.

Kumeyaay Community College. Photo from Yelp.Cuyamaca and Kumeyaay Community College will resume online classes in the fall, and no one knows when social distance learning will come to an end.

Solving this access problem, which is a symptom of centuries of social and economic deficits in Indian Country, has to become a high priority before too much damage is done, Banegas said.

“It highlights this huge digital divide in Indian Country that has been pervasive for years and years. It’s something I've been zealous about,” said Banegas, who has lived on the Barona Reservation for a large portion of his life. “Our lives are all online now. Our internet is going to either help us or impede us from progressing into a modern economy.”

The impact the digital disparity is having on Native American students is part of a state and country-wide discussion.

During a recent online lecture about digital challenges on reservations, presented by the Idyllwild Arts Native American Studies Summer Program, News From Native California editor Terria Smith addressed the problem.

“I’m pretty concerned, especially for my tribal community, because the majority of them don't have high speed internet access. On our allotment we don't have it,” said Smith (Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla). With students staying home, she added, “I’m wondering what education looks like for families who don’t have the access. How are they going to continue on with their learning?”

Smith mentioned a few programs and services designed to help, including MuralNet, a nonprofit that helps Native communities “affirm their internet sovereignty, and build their own networks,” according to the organization’s website.

Banegas said he has engaged with the Barona Tribal Council and IT department to develop a plan, but they don’t seem to recognize the urgency.

“It’s a generational thing,” Banegas said, adding that the reservation’s Elders primarily use the internet for email. “They don’t even know how far behind we are because they never leave the reservation.”

The Barona reservation’s IT office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“My community is so incredible to me and paid for my education and given me everything I have. All I’ve ever wanted to do was give back and change the negative and focus on the positive,” Banegas said. “I’m frustrated because I just want a solution. I'm not blaming anyone. Let’s just figure this out. I don't care who or what it takes. In the end, what I’m upset about is the students.”

Not everyone has the resilience of the Nuneses, but they’re proof that some Native American students are willing to go to great lengths to continue their education –– even if it means they have to dodge the gear shift and discipline their child while doing it.

“What you have to overcome defines who you are,” Scott said. “Having to fight against that using limited resources somehow made us that much more determined.”

More Stories Like This

Dr. Shelly C. Lowe to Be Inaugurated as IAIA President March 26–27Tlingit Language Courses Expand for Students to Learn With Families At-Home

American Education Has Failed Its First People, But Hope Is On The Horizon

Bipartisan Vote Keeps Institute of American Indian Arts Alive and Funded

New UNLV Executive Certificate Focuses on Tribal Governance, Economic Leadership

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher