- Details

- By Darren Thompson

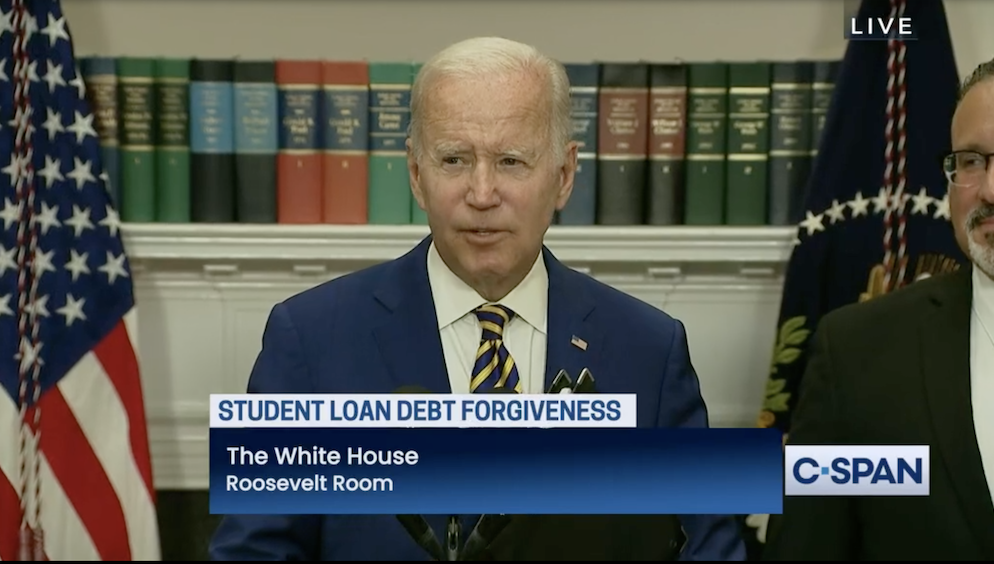

President Biden announced this week that the federal government would cancel up to $20,000 each for millions of borrowers who have federal student loans. That’s welcome news for many Native Americans saddled with student loan debt — a reality despite the widely believed misconception that all Indigenous students can earn a post-secondary degree for free.

Student debt is a reality in Indian Country, especially for Native women. While the average borrower has more than $30,000 in student loan debt, the number is much higher for women of color, according to this report in The 19th. On average, Native American women owe $36,184 a year after college graduation compared to White women, who owe $33,851, according to the American Association of University Women.

Biden’s plan offers debt relief for students with loans from the U.S. Department of Education. Individual borrowers who are single and earn less than $125,000 annually will qualify for $10,000 in debt cancellation; borrowers who are married and file taxes jointly, or head of household, qualify for the debt cancellation if combined annual income is under $250,000.

Borrowers who received a Pell Grant and meet the income requirements can qualify for an extra $10,000 in debt cancellation. Students who didn’t graduate, but still borrowed for the DOE, may still qualify for debt cancellation. Biden’s plan also decreases the debt burden for certain borrowers, such as those involved in public service loan forgiveness programs or repayment plans based on annual income, capping repayment at 5 percent of monthly earnings.

"President Biden’s announcement bolsters their efforts to ensure that every Native student who wants a higher education can get one,” Cheryl Crazy Bull, president and CEO of the American Indian College Fund, said in a statement. “We appreciate the student loan relief program on behalf of our students and their families.”

While appreciative of the student-debt relief program, it doesn’t fill the funding and repayment gap that still exists for Indigenous students, according to Crazy Bull and other advocacy groups for Native education.

“Sufficient financial resources are still unavailable for Native students, according to the National Study on College Affordability for Indigenous Students, released by the College Fund and three other National Native Scholarship Providers,” Crazy Bull said. “It is clear college loans are a deterrent to the financial health and well-being of Native students and graduates.”

According to the National Study on College Affordability for Indigenous Students, researchers found the primary obstacle for Indigenous students to complete college is affordability, causing overall college student attrition. The study found that only 36 percent of Indigenous students entering four-year colleges and universities in 2014 completed their academic degrees in six years, as compared to 60 percent of all other students.

“The incredible data produced by this national study will shed a more direct light on our Indigenous students and the financial barriers that they face along their educational journeys,” said Sarah EchoHawk, chief executive officer of the American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES), in a statement.

Biden’s plan also extends the pause on monthly student loan payments that started during the pandemic until at least January 2023. The announcement also comes with a proposal for the U.S. Dept. of Education to create a more affordable repayment plan that is based on income.

“Deferring repayments through the end of 2022 gives our students more time to recover from the devastations of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Crazy Bull said. “And the forgiveness of student loans combined with state tuition waivers for Indigenous students and scholarships from the American Indian College Fund and other Native scholarship providers work together to make higher education more accessible for Native students.”

Native students share the main reason they pursue a college education is to give back to their families and their Tribal communities, according to Crazy Bull. “If graduates cannot afford to return home to work, they cannot give back. If student loans are a burden, graduates cannot build their families’ cultural and financial wealth.

“We want our people to be able to own homes, have retirement funds, and support cultural and social activities, such as name-giving and celebrations.”

To see if you qualify for student loan cancellation, go to https://studentaid.gov/manage-loans/repayment/servicers for more information.

More Stories Like This

Bard College Center for Indigenous Studies (CfIS) Hosts Annual Symposium With Keynote Speaker Miranda Belarde-Lewis on March 9–10American Indian College Fund Announces Spring 2026 Faculty Fellow Cohort

Navajo Nation Signs $19 Million Diné Higher Education Grant Fund Act into Law

Dr. Shelly C. Lowe to Be Inaugurated as IAIA President March 26–27

Tlingit Language Courses Expand for Students to Learn With Families At-Home

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher