- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

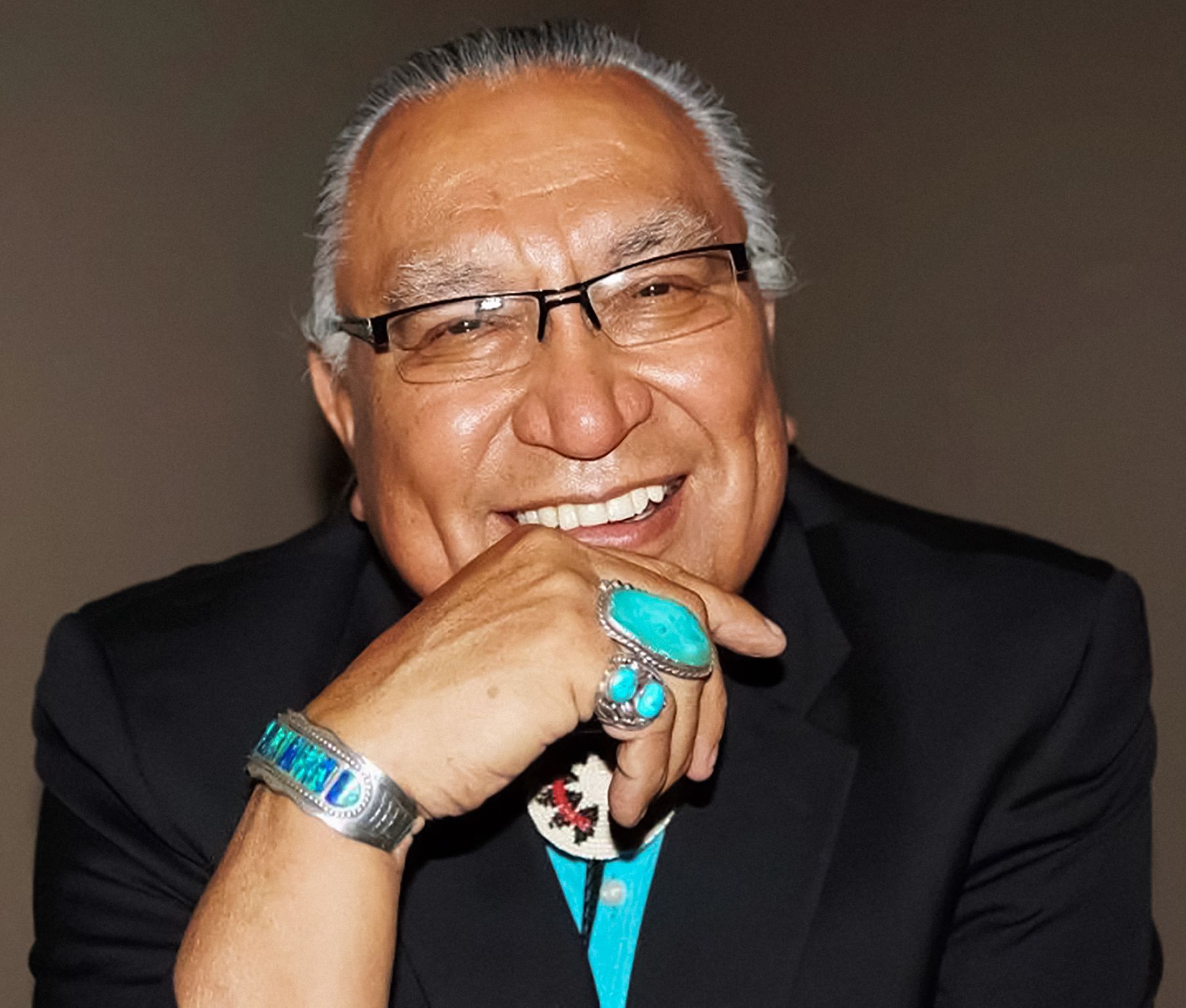

TULSA, Okla.—Negiel Bigpond is a Yuchi elder, an Evangelical pastor, an Indian boarding school survivor and an activist. Since 2003, he’s worked with Sam Brownback—the former U.S. Senator, Kansas Governor and present U.S. Ambassador for Religious Freedom—to pursue a formal apology from the mouth of the United States president for atrocities committed against Native Americans.

His work nearly succeeded in 2009, when President Barack Obama signed a Department of Defense Appropriations Act that admitted to “ill-conceived policies and the breaking of covenants by the Federal Government regarding Indian tribes.”

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

But the bill, which also “urge(d) the President to acknowledge the wrongs of the United States against Indian tribes in the history of the United States in order to bring healing to this land,” never resulted in a spoken apology.

Now, with news of Indian Boarding Schools generating awareness of injustices committed against Native Americans, Bigpond and Brownback’s initiative — called “The Apology” — has released a multiple-part film series on YouTube.

Bigpond spoke with Native News Online on the importance of an apology, his own boarding school experience and his path towards forgiveness, and reconciling his role within a religious institution that had a hand in inflicting some of the harm.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

WARNING: This story contains distressing details about residential and boarding schools for Indigenous children.

NNO: Can you start by introducing yourself and giving us your background?

Bigpond: I'm a fourth generation minister— my great grandfather, my grandfather, and my father before me were Methodist ministers, and my great uncle was the first missionary to the Yuchi people. Bigpond is a kind of a unique name in the sense that on the Trail of Tears — by a town now called Bristol, Oklahoma — they called it Bigpond. That's where they put a lot of the Native people when they came from the Trail of Tears.

I was raised in Mounds, Oklahoma, about 17 miles from Tulsa. I'm a musician. I went to boarding school in 1965 (from) the seventh grade...to twelfth grade. But at the boarding schools, if you were in seventh grade, you were probably doing a fourth-grade curriculum. It just wasn’t the best of the best. I (eventually) got my doctorate in divinity. And also, I went to Oklahoma University to get my education in substance abuse and began to work with the Native kids with substance abuse.

Can you tell us about the project—including the docuseries ‘The Apology’—that you’ve been working on with former Kansas Senator and Governor Sam Brownback?

I've been working on it since 2003, when we met with Senator Brownback in his office and we prayed together with the treaty book. Afterwards...I said ‘Senator, I think it's time that the United States government asked for forgiveness for all the atrocities that took place.”

What I’ve asked is for a president to stand in a place of authority and ask our people for forgiveness.

Even in the apology Senator Brownback wrote and Obama signed in 2010, it was for the purpose of healing our people spiritually. It has nothing to land or money or anything else.

Our people called (that bill) a joke, because he just signed the bill. He didn’t talk about the bill.

What I’m asking is for our government to apologize.

What’s the importance of an apology?

It’s a spiritual healing that we’re after with the apology. That’s all it is. The prophecy is that when the United States’ President releases that apology, he'll look to the east. I thought that was the direction east, but what it is, is Israel.

Israel and our Native tribes are unique in the sense that we never forgot our language, we never forgot how we were raised.

What was your personal experience like in boarding school?

My experience with boarding school wasn't all that good. I went to Chilocco (near) Arkansas City. It was run by the Methodists. A lot of the kids were coming from reservations, very poor situations. So I didn’t have the things that they had, not coming from a reservation. But that didn't bother me so much as that they didn’t want you speaking your language. They wanted you to speak English.

If you did something wrong, they would give you what they called hours, and you had to work those off. You'd scrub the floors, you'd scrub the stairwells. If you were caught speaking your language or being disobedient, they would put you in a small square box and put it in a corner, and you had to have your nose against the wall all night long. I tried to run (away) three or four times.

We just accepted. It didn't really dawn on me or hit me until later in my years that I had to, to put up with things like that.

How have you come to terms with that experience, and reconcile with the fact that religious organizations—including Evangelicals—had a hand in running a large portion of the Indian Boarding Schools across the country, where so many children experienced abuse, neglect, and mistreatment like the punishments you described.

It’s a process. There was some bitterness in me later and I wasn’t the ideal son. But as the years went on, I came to be closer with my parents and closer to God. I went back to boarding school after it was closed down four or five times to try to find forgiveness in my heart for people and what happened to me.

Some can’t forgive because they’re thinking I'm telling them to forget. If we forget, it’s almost like I'm asking them to dishonor what they have gone through. There were a lot of sexual things that happened to kids in those boarding schools, too, that some of those leaders did. You don’t have to forget to forgive. You just forgive. Like I've forgiven this nation for the Trail of Tears, the Removal Act, and all these things. I haven't forgotten.

To forgive is to carry on and to allow love to be a part of your life, to be a part of your family, to be a part of carrying on to better things.

What would you say to Natives that see organized Western religion as just another form of colonization?

I would say that to them: look at history. God is nothing new to us. We knew God before Columbus came. We knew God before there was any bible. We knew God a long time ago. When I pray in my Native language...I say...in other words: ‘Oh great one, I come with a good heart, a clean heart.’

So when I hear (people connecting Western religion to colonization), I say: Do you know your tribal history? Do they mention God in your language? And of course they say yes. It’s just there. There’s no way you can get out of it.

What responsibility do organizations like the Catholic church and the Evangelical churches have on owning up to their roles in assimilative US policies?

All those that were involved need to apologize. It will help our nation, and it will help these Christian organizations that went about it the wrong way. They messed up. They shouldn't have done what they did. They just need to get through that by asking for forgiveness, and then move on. It'll help our people for certain.

What’s the status of the campaign? Any response from President Biden?

I think I think the apology is coming. I think it’s real close. I think this president will do it.

Interview conducted and condensed by Jenna Kunze. Photo courtesy of Negiel Bigpond.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story has been updated to reflect the proper location of the Chilocco boarding school and the year (2003) when Dr. Bigpond first met with former Sen. Brownback.

More Stories Like This

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement ActivitiesChickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher