- Details

- By Kelsey Turner

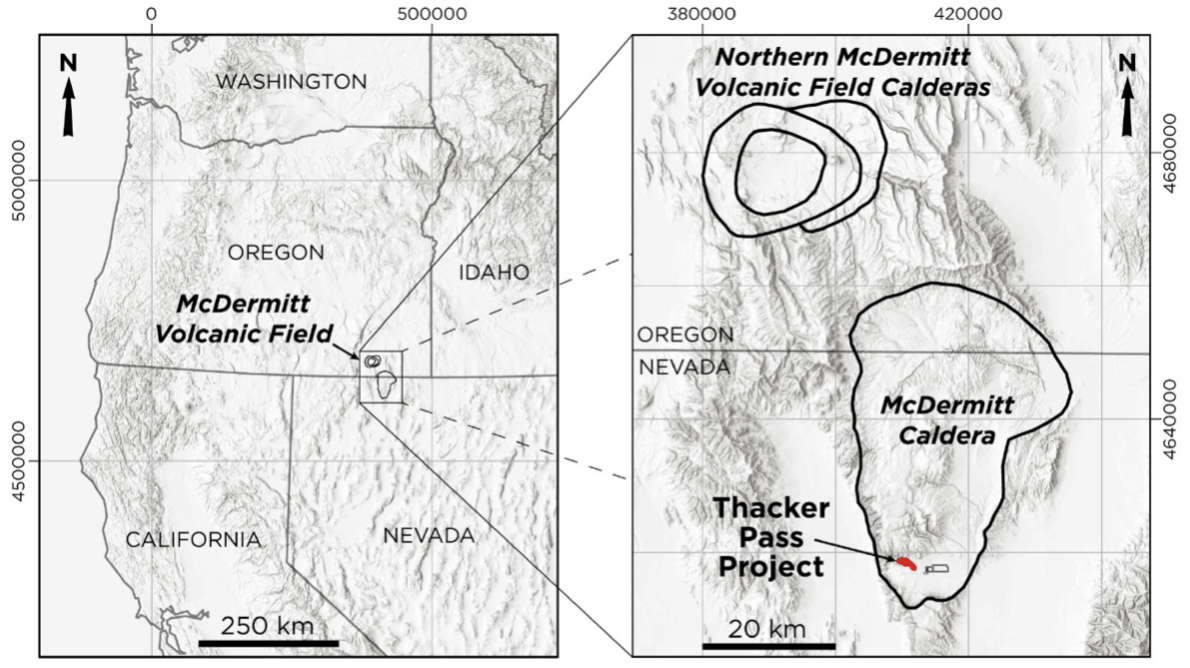

On Nov. 29, the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony (RSIC) and Northern Paiute group Atsa Koodakuh wyh Nuwu (People of Red Mountain) filed a first amended complaint against the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The complaint, part of a lawsuit filed against BLM in February 2021, alleges that the bureau violated five federal laws when it issued permits to the Lithium Nevada company for a lithium mine in northern Nevada’s Thacker Pass. Lithium Nevada, part of Canada-based Lithium Americas, intends to start mining there next year.

To the RSIC and the People of Red Mountain, Thacker Pass is sacred land, home to traditional foods, medicines, and ceremonies. But to the extractive industry, it’s the U.S.’s largest known source of lithium, an element used in rechargeable electric car batteries.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

“We want to protect that place for the integrity of our people, and the spirits, and things that a lot of people care about with our Native traditions and culture,” said Daranda Hinkey, secretary for the People of Red Mountain. “We want to protect it for not only us right now, but for the people after us.”

The RSIC has members, employees, and residents with direct cultural ties to Thacker Pass, RSIC chairman Arlan Melendez and Cultural Resource Program director Michon Eben said in an emailed statement to Native News Online.

Melendez and Eben said the BLM notified only three of Nevada’s 27 tribes about the mine.

“We were shocked that only three tribes were notified,” their email stated. “If we are going to have this new rush for lithium, it is going to cause the same kind of genocide the gold and silver rush had on Native Peoples in Nevada.”

Thacker Pass is also the site of two massacres involving Native people: The first occurred between Paiute and Pitt River Indians, and is documented only in oral history. The second was on Sept. 12, 1865, when federal troops killed at least 31 and possibly as many as 70 Paiute men, women, and children.

Hinkey said building a lithium mine in Thacker Pass would mean digging up a cemetery.

“Our people are tied to the land, and so when we bury our people, or when our people are massacred like that, it’s different,” she said. “I feel like the rest of society doesn’t truly understand that, because Native people are connected in different ways.”

The amended complaint alleges that in permitting the lithium mine, BLM violated the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), the Archeological Resources Protection Act, the Administrative Procedure Act, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act.

The NHPA requires BLM to identify all historic properties in the project area before approving a permit. The bureau failed to identify at least four historic properties on the Thacker Pass site, despite its General Land Office having records of them, the complaint says. These include records of the 1865 massacre.

“Either they did not adequately search their own General Land Office records, or they did, and they decided to hide what they found,” said Will Falk, an attorney representing the RSIC and the People of Red Mountain. “Either scenario is illegal.”

The BLM has claimed it did not have previous knowledge of Thacker Pass’ historical and cultural significance. But evidence presented in the complaint includes its records of a 2009 telephone conversation in which then-Fort McDermitt Tribal Chairman Dale Barr told BLM archeologist Peggy McGuckian of the area’s significance.

In that conversation, McGuckian notified Barr about a project BLM was permitting in Thacker Pass and Kings River Valley. Barr expressed his concerns about it, telling McGuckian the oral history of the Paiute Pitt River massacre. But BLM’s subsequent environmental assessment for the project noted “Dale Barr stated that the Tribe had no concerns about the Project.”

This conversation shows BLM did have previous knowledge of Thacker Pass’ significance, said Max Wilbert, co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass, a movement protesting the mine.

The NHPA also requires BLM to consult with tribes that may be affected by the project before issuing a permit. In its effort to initiate consultation, BLM sent letters to several regional tribes in December 2019. When the tribes did not respond, the complaint says BLM did not follow up.

The BLM handbook on tribal relations explicitly says, “sending a letter to a Tribe and receiving no response does not constitute a sufficient effort to initiate tribal consultation.”

“BLM, by their own definition, conducted zero consultation with Native tribes,” Wilbert said. “And they’ve been lying about that since they issued the permit.”

Falk said these allegations provide grounds for the judge to place the project on hold while BLM reviews the historical information and consults with tribes that consider the massacre site sacred.

Hinkey said the People of Red Mountain have sent emails to BLM and have never gotten a real response.

“We’re trying to fight as hard as we can from every angle,” she said. “If the Thacker Pass lithium mine was to go through, it feels as if our voices are not being heard.”

More Stories Like This

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement ActivitiesChickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher