On July 9, the Supreme Court issued one of the most important decisions for Native land and treaty rights in the history of the United States. In McGirt v. Oklahoma, the nation’s highest court upheld that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation still has a reservation. Justice Neil Gorsuch, who authored the majority opinion, concluded that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s land rights were guaranteed by treaty, never reversed by Congress, and that the court would “hold the government to its word.”

On the ground in Oklahoma, the decision was immediately applied to the reservations of four other tribes—Cherokees, Seminoles, Choctaws, and Chickasaws—affirming that much of eastern Oklahoma, which encompasses about 40 percent of the state, is indeed a reservation. For more than a century, Oklahoma had brushed the treaty rights of these five tribes aside. In McGirt, the Supreme Court said these treaty violations must stop.

Many tribal citizens and advocates are worried, however, that the historic victory may be undercut by an “Agreement-in-Principle” released last week. Last Thursday, Oklahoma released an agreement between the Oklahoma Attorney General's office and the five tribes, outlining the principles of a law the tribes and the state would ask Congress to pass. But by the end of the day, Seminole Nation Chief Greg P. Chilcoat said his tribe “has not been involved with discussions,” and removed his support. On Friday, via Facebook, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Principal Chief David Hill announced the tribe “does not agree that legislation is necessary.” It appears that at least the Cherokee Nation and Chickasaw Nation still support the proposed legislation, but its future remains uncertain.

Between the impact of the Supreme Court ruling, existing laws that govern reservations, and the changes outlined in the Agreement-in-Principle, there is a lot for tribal citizens to unpack. Lauren King is an Indian law professor, attorney at Foster Garvey PC and citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. She spoke with Rebecca Nagle over email for Native News Online about what the agreement means for tribal citizens and eastern Oklahoma.

First off, what changes in eastern Oklahoma after the McGirt decision without this Agreement-in-Principle? Basically, how would life move forward in eastern Oklahoma if Congress does nothing?

That is a great question, because one of the biggest issues I’ve observed since the McGirt decision was released is misinformation being spread in the press and on social media due to a lack of understanding of jurisdiction in Indian Country. And that’s completely understandable, because jurisdiction generally is not an easy thing, but this confusion is not an excuse for misguided legislation.

In a fundamental sense, nothing has changed in Oklahoma following the Supreme Court’s decision in McGirt. These tribal reservations have always existed. The Supreme Court held in McGirt that Oklahoma has been illegally exercising criminal jurisdiction over crimes involving Indians on the Muscogee (Creek) reservation. Because the treaties and history of four other tribes—the Cherokee Nation, Seminole Nation, Chickasaw Nation, and Choctaw Nation—are similar, the implication of the McGirt ruling is that those four tribes’ reservations still exist as well. This map shows where in Oklahoma these reservations are located:

Following the decision in McGirt, the normal jurisdictional framework that governs reservations will govern here.

It’s important to know that when a court rules that a reservation still exists, it doesn’t change any land ownership within the reservation. Private landowners continue to own their lands, and any trust or restricted parcels owned by the tribes or tribal members also continue in that trust or restricted status.

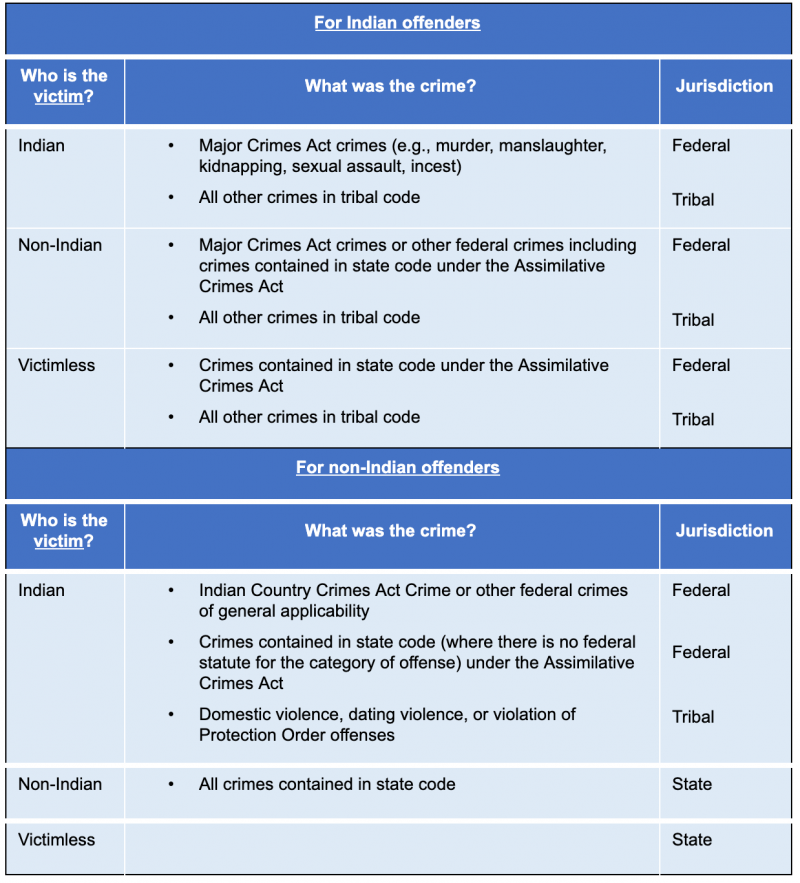

Criminal jurisdiction simply means who has jurisdiction to prosecute crimes committed within a reservation. Here, it does not matter who owns the land upon which the crime is committed. The following simplified version of a chart created by the Department of Justice gives a simple overview of criminal jurisdiction on reservations:

In the simplest terms, tribes and the federal government have jurisdiction over crimes involving Indians, and the state has jurisdiction over crimes committed by non-Indians against non-Indians. (I use the term “Indian” here because that is the term used in the law. For those who wonder what term Natives prefer, ask the tribes. I personally usually use the term “Native.”)

Civil jurisdiction simply means who has jurisdiction over non-criminal matters that arise on a reservation—like taxation, regulating businesses, lawsuits and even protective orders. Here, it does matter who owns the land. Tribes generally have civil jurisdiction over tribal members and non-members on trust and restricted lands. Tribes generally do not have regulatory jurisdiction over non-members on non-member-owned lands unless (1) that non-member consents to the tribe’s jurisdiction or (2) the non-member’s conduct is threatening the political integrity, economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe. This rule generally applies to taxation as well.

So given the way criminal jurisdiction typically works on reservations, what does the Agreement-in-Principle change?

Normally, tribes have criminal jurisdiction over all crimes involving Indians that occur on reservations, and the state has criminal jurisdiction over crimes by non-Indians against non-Indians. The Agreement-in-Principle would change that by giving Oklahoma criminal jurisdiction over all crimes involving Indians throughout the reservations, except on the tiny percent of the land within the reservations that is trust or restricted land. For example, within the Cherokee Nation that would be less than 2 percent of the reservation. In other words, the Agreement-in-Principle expands Oklahoma’s jurisdiction on the five tribes’ reservations by giving the state jurisdiction over crimes involving Indians that it would not otherwise have.

If this Agreement-in-Principle were to become law, then every time law enforcement responds to a crime, they would have to evaluate the status of the individual parcel of land where the crime was committed. Requiring this will burden law enforcement and certainly make it more difficult to figure out who has jurisdiction.

That sounds like a pretty big shift. Would civil jurisdiction under the Agreement-in-Principle change too?

Like with criminal jurisdiction, the Agreement-in-Principle expands Oklahoma’s civil jurisdiction. As I explained, normally tribes have civil jurisdiction (including taxation authority) within their reservations over (1) tribal members, (2) non-members doing business or residing on tribal trust and restricted lands, and (3) non-members outside trust and restricted lands (but within the reservation) whose conduct threatens the political integrity, economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe. States may not tax the activities, income, or property of tribes or tribal members on their reservations absent a clear statement from Congress.

The Agreement-in-Principle gives Oklahoma civil jurisdiction over everyone within the reservation except on the tiny percent of the land within the reservations that is Indian trust or restricted land. Additionally, although the Agreement-in-Principle does not allow Oklahoma to tax tribes, tribal officials, or tribal entities, it does not include any tax exemption for tribal members.

Another important note about civil jurisdiction in the Agreement-in-Principle is that it codifies a Supreme Court decision—Montana v. United States—that many believe is based on a prejudiced, mistaken and limited view of tribal sovereignty. Many tribal advocates have criticized Montana because it has been used by corporations and non-Indian domestic abusers to insulate themselves from liability for their conduct on tribal lands that harm Native people. This codification also poses serious potential risks for Indian women abused by non-Indian men because under current law, tribal courts can issue protective orders for non-Indian men who abuse Indian women on tribal lands. But if Congress passes a law limiting that civil jurisdiction, it is unclear what would happen to Indian women who need a protective order from an abusive non-Indian man in a tribal court.

The problem with agreeing, even if in principle, to relinquishments of tribal sovereignty is that once you agree to give it up, there is no guarantee that you can get it back. And, we have no control over how much Congress, if encouraged to do so, would elect to take.

One of the reasons I am hearing for why tribes should make these concessions to Oklahoma is that they are necessary. After a court rules a tribe still has a reservation is it necessary or normal for Congress to get involved?

No. I am not aware of any case where Congress enacted legislation after a court affirmed a reservation’s status. The most recent Supreme Court decision on this subject matter was Nebraska v. Parker in 2016, where the court ruled that the Omaha Tribe’s reservation still existed. No legislation was passed in reaction to that ruling. Instead, the parties assumed the jurisdictional authority that they were supposed to have had all along, without chaos or disruption.

Any issues related to criminal jurisdiction can be addressed through intergovernmental agreements between federal, state, and tribal authorities—a practice that is commonplace in tribal communities and reservations in various states across the United States. The Creek Nation alone has cross-deputization agreements with 40 out of the 44 county and municipal jurisdictions in the Creek Nation reservation. And, immediately following the Supreme Court’s decision, all United States’ Attorneys within Oklahoma issued a statement confirming that the United States would utilize all resources necessary to arrest and prosecute Indians who commit crimes within reservation borders, and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation has promised to do the same. In short, there is nothing that requires Congress to get involved.

It is true that Congress can choose to disestablish a reservation even after a court affirms its continued existence. However, to make such a choice in 2020 would be a shocking and reprehensible breach of the solemn promises made to the tribes.

There was a time in history when our ancestors were forced to cede our ancestral homelands—the southeastern United States—in the face of the threat of death and involuntary removal. But this enormous cession was made in exchange for a promise that we would have a new home, forever. The 1866 Treaty states that the Muscogee (Creek) reservation shall “be forever set apart as a home” for us. In this day and age, tribes should no longer have to live in fear that the government that promised this land to us will break its word.

The tribes too have an obligation—one we owe to our ancestors. They trusted that we would protect for future generations this new homeland for which they gave up so much—this new home upon which we rebuilt our ceremonial grounds, our governments, our way of life. And I would hope that the trust they placed in us would compel our tribal leaders to honor our ancestors and the sacrifices they made by standing strong and protecting our sovereignty.

There have been reports that Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter is working with Senator Lankford on a bill that would include principles from the Agreement-in-Principle that Attorney General Hunter released Thursday morning. Do you know if any of the Five Tribes’ elected leadership or citizens have been able to review the draft language of this bill or provide any input on what it should say?

I have not been involved in any communications that may have taken place regarding the bill language, but given the timing of these reports, I am confident that there has not been an opportunity for all five tribes’ elected leadership and citizens to review the draft language of this bill and provide input. I certainly have not seen any Tribal Council resolutions approving any such bill. On July 10, Seminole Nation Chief Chilcoat responded to Attorney General Hunter’s release of the proposed agreement, stating that: “To be clear, the Seminole Nation has not been involved with discussions regarding proposed legislation between the other four tribes and the State of Oklahoma.” Also on July 10, Muscogee (Creek) Nation Chief David Hill stated that the “Muscogee (Creek) Nation is not in agreement with the proposed Agreement-in-Principle released by the State of Oklahoma yesterday.” Notably, there are no signatures on the Agreement-in-Principle.

More Stories Like This

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection RequirementsAmerican Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Northern Cheyenne Push Back Against Trump Administration’s Effort to Alter Little Bighorn History

Florida Man Sentenced for Falsely Selling Imported Jewelry as Pueblo Indian–Made

Navajo Nation Declares State Of Emergency As Winter Storm Threatens Region

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher