- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

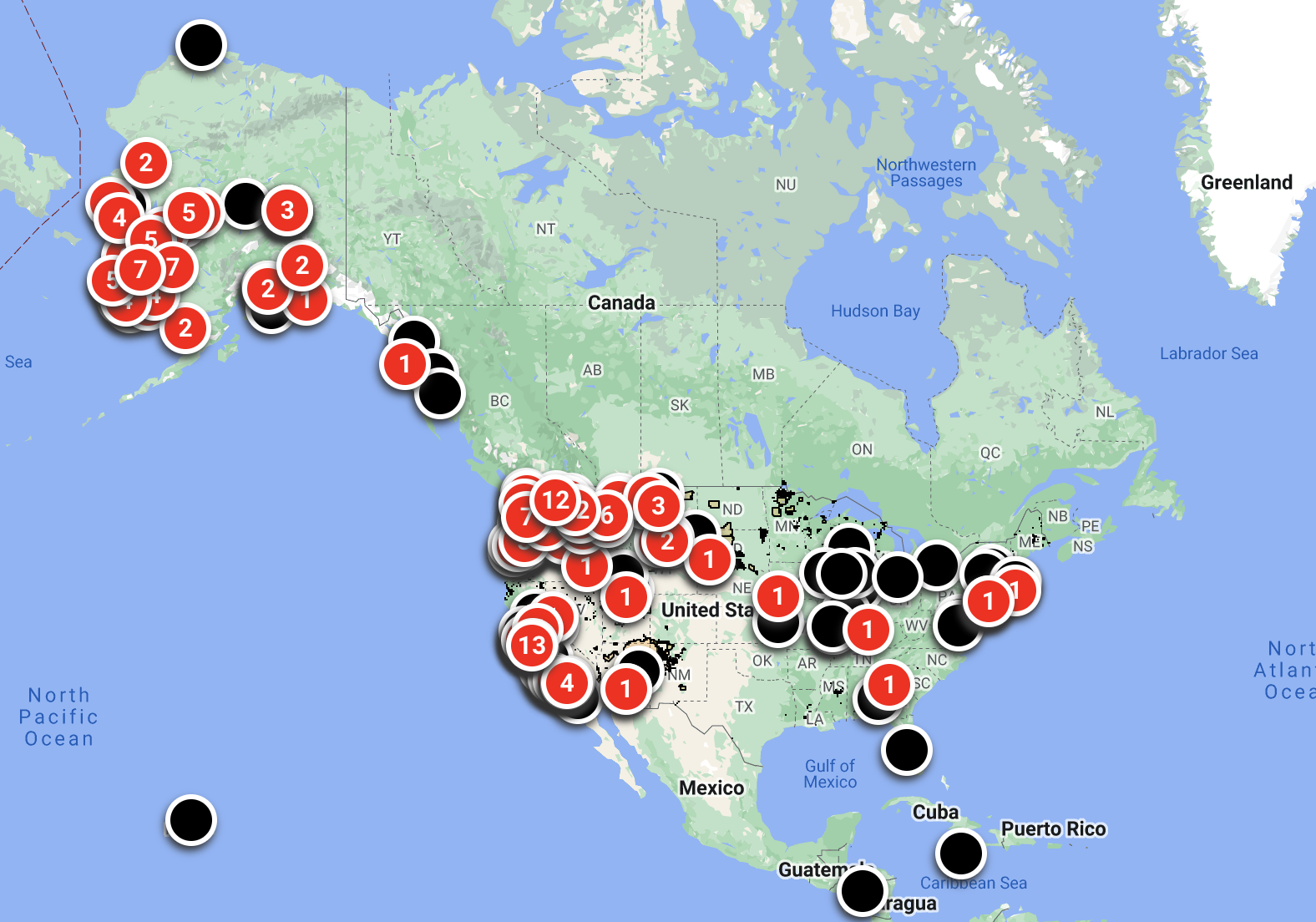

That’s what’s depicted by Desolate Country: Mapping Catholic Sex Abuse in Native America, an interactive map that plots the years and locations of 99 priests and 13 brothers of the Jesuits West Province. Of them, 47 of the men with credible allegations of abuse against them spent time working at Native missions.

The Jesuits West Province—which includes Arizona, Alaska, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, and Washington—formed in July 2017 as a merger between the former California and Oregon Provinces after the Oregon Province paid close to $200 million in settlement claims to Indigenous survivors of sexual abuse, leading to bankruptcy.

The map’s creators— religious studies scholars Katie Holscher and Jack Downey—used the information published by the Jesuits West Province as a requirement of the bankruptcy settlement.

The sexual abuse disclosure list is one of almost 200 published by US Catholic dioceses and religious orders, but it stood out to Holscher and Downey for its unusual inclusion of details often left out, such as information about where each priest worked and the dates of the abuse they committed. The provincial of Jesuits West leader at the time of the list’s publication, Fr. Scott Santarosa, said the order released information on where the priests and brothers worked and abused since 1950 “because the People of God demand and deserve transparency” and in hopes “that this act of accountability will help victims and their families in the healing process.”

THE PROJECT

Downey and Holscher decided to illustrate the disclosure list to make clear what is not immediately apparent to a person scrolling through a 26-page spreadsheet: that a significant number of abusers worked within Indian Country.

“The list itself is really opaque,” Downey, an associate professor of Religion and Classics at the University of Rochester, told Native News Online. “It’s just an excel spreadsheet with a bunch of [names and] places. Unless you have a really impeccable memory, there’s no way of taking page one and comparing it to page 20.”

Downey and Holscher received funding from the Religion & Sexual Abuse Project and spent two years piecing together the map.

“Oftentimes disclosure lists just include the names of priests, and the Jesuits had actually given us this level of information that would allow somebody to be pretty systematic about thinking where these guys were over the course of their careers, from the day they were ordained to the day they died,” said Holscher, an associate professor of American Studies and Religious Studies at the University of New Mexico. “It almost felt like it was intended to translate into a map; otherwise, why line up years and locations together?”

The public map allows users to search for a priest or brother by individual names to see the institutions where they spent time working and to read more about each priest or brother at BishopAccountability.org. The map has a function to “watch this Jesuit move,” which illustrates the migration of each clergy member throughout their career and the time periods where they were credibly accused of abuse. According to Jesuits West Province spokesperson Tracey Primrose, claims were deemed credible based on internal investigations conducted by the Jesuit provinces. The provinces determined a claim’s credibility “based on the facts and circumstances of each case where it is reasonably plausible that the sexual abuse of a minor or vulnerable adult occurred,” Primrose told Native News Online. Jesuits West also listed the names of deceased Jesuits with claims “although the Jesuit was unable to defend himself” and those whose names were already made public in diocesan listings or bankruptcy settlements.

THE LIMITATIONS

While the map does show the number of credibly accused priests, it doesn’t show the number of victims, and it doesn’t prove that abusers were specifically being sent to Native missions, Holscher pointed out.

“The list doesn’t show intent,” she said. “Just because men ended up clustering at particular locations, it doesn’t demonstrate that the men were dumped there. We know from the archival work that sometimes bad priests were dumped on reservations, and we have anecdotal evidence that this sometimes happens. But it’s also the case that sometimes priests who had no previous records of trouble began to abuse once they were at these locations.”

The Jesuits West list also named 16 men without their dates of abuse, which made it impossible to accurately display abuse with red dots across the map.

“For those men, there are no red dots on the map. They’ll show up as black dots, but we couldn’t actually create a red dot if we didn’t have the dates, and without the dates, we also couldn’t pinpoint where the abuse occurred for them,” Holscher said.

Still, the current map does give shape to certain narratives. Clusters of abuse appear on St. Mary’s Mission on the Colville Reservation in central Washington, evidencing a boarding school where priests abused Native children while acting as foster parents. The Pacific Northwest Indian Center in Spokane, Washington, also had 12 credible accounts of abuse.

Sacred Heart Jesuit Center in Los Gatos, California—where many Jesuits get sent to retire—hosted 13 abusers. But it’s likely that the abuse didn’t happen at the retirement home, Holscher said, but rather that the priests were immediately sent there as a result.

THE FUTURE OF TRUTH TELLING

Below their map, Holscher and Downey write a few paragraphs explaining the background of the disclosure list and how the map can be used. They told Native News Online that they intentionally left out their “takes” on the information to keep it simple and accessible. Instead, they invite viewers to consider what the map’s clusters suggest about the causes and the character—as well as the consequences—of clerical sexual abuse.

“The answer is: it’s complicated, and there are so many layers,” Holscher said. “That’s where the archival digging becomes necessary because that’s where you have to understand the motivations of superiors that sent them there. That’s where you have to start to understand the structures of institutional life that made it an easy place for priests to abuse kids because those are all pieces of the answer. None of them is the entire answer.”

Downey echoed that there is a “constellation of factors” that have contributed to clerical sexual abuse in Native communities. They said that they hope their map works in conversation with survivor-centered approaches and boarding school accounts and serve as an “information distribution vehicle.”

“It’s still such early days, at least from the Catholic side of things in terms of public awareness of the breadth and depth of the problem,” Downey said. “It’s only been a couple of years that even scholars of Catholicism have started thinking about abuse as a norm rather than an exception.”

More Stories Like This

Navajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement PlanNCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher