- Details

- By Levi Rickert

Opinion. Teague Rutherford (Aaniih and Nakoda) will begin his third year of dental school this fall at the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health. He remembers clearly the moment he decided to become a dentist. He was nine years old and was receiving treatment from an off-reservation dentist. He loved how the dentist treated him with compassion.

It was a sharp contrast to the traumatic experiences at an Indian Health Service (IHS) clinic on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana where he grew up. He’d gone the reservation clinic, but the dentist did not numb him properly. He was in so much pain that his mother snatched him from the dental chair and brought him home.

Still in pain, his father took him back to the same doctor at the same clinic, and the result was, not surprisingly, the same. When Rutherford said he was in pain, the dentist told him to be quiet. His father brought him home without proper relief. Then his grandmother took him back to the same doctor at the reservation clinic, but the result was the same.

Finally, some time later, he visited the off-reservation dentist, who treated him with compassion and understanding. At that moment, Rutherford told me, he decided that he would grow up to become a dentist who would treat Native Americans with compassion and dignity.

He remembers thinking, “When I grow up I’m going to be a dentist and treat my tribal community.”

Rutherford recounted his experiences to me during an interview I conducted this past week. He was among several Native American dental students and dentists studying to receive their licenses to practice dentistry.

The interviews were conducted at the Society of American Dentists (SAID) conference in Albuquerque. Portions of the interviews will be aired on an upcoming Native News Online webinar entitled "The Mouth is the Gateway to Good Health."

Several of the Natives that I interviewed stated that they did not think they were smart enough to become a dentist. However, they overcame self-doubt because they were influenced by someone in their lives who provided guidance.

Beyond the inspiring and compelling interviews I conducted, the SAID conference provided me with a better understanding of the needs in Indian Country for better dental care.

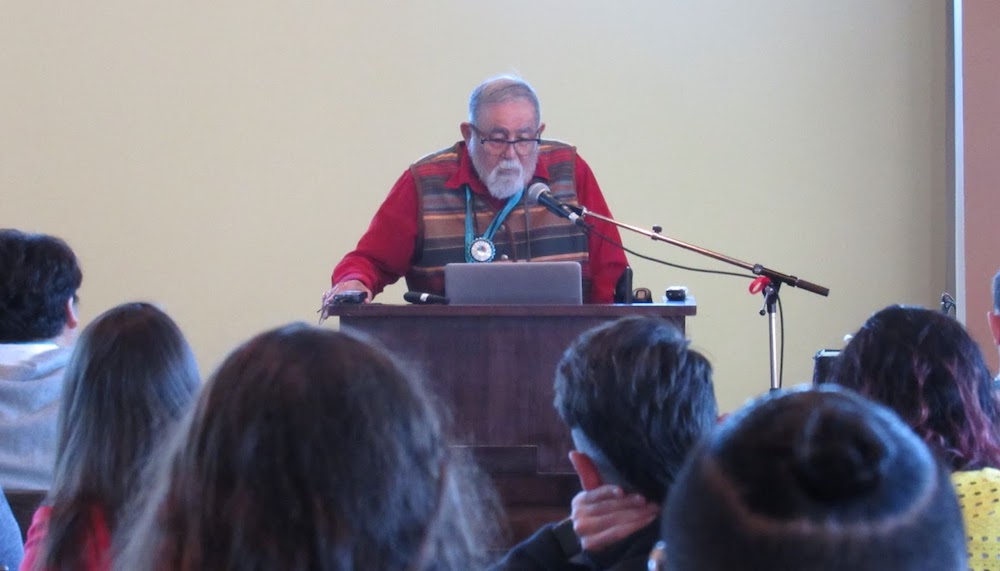

An added treat for me was when I met the most popular person in attendance: Dr. George Blue Spruce (Laguna Pueblo), who became the first Native American dentist in 1956. Dr. Blue Spruce, who is two months shy of his 92nd birthday, was treated with well-deserved respect by fellow Native American dentists and other dental professionals who attended the conference.

It took another 19 years for another Native American to become a dentist, which occurred when Dr. Jessica A. Rickert became a dentist and the first female Native American dentist ever. For the record, Dr. Rickert is my sister — a fact that I’m more than proud to admit.

Doctors Blue Spruce and Rickert were first-of-their kind pioneers in Native dentistry. Decades later, unfortunately, Native American dentists still find themselves in rare company.

Today, there are approximately 400 Native American dentists, which doesn’t even equate to one per tribe because there are 574 federally recognized tribes in the country.

This fall, there will only be 23 Native Americans dental students studying to become dentists.

And here’s the important thing to remember: The need for more Native American dentists is heightened by the fact that in any given year there is a 30 percent vacancy rate to fill dentists’ positions at IHS clinics across Indian Country.

The lack of dentists in Indian Country contributes to poor health among Native Americans. It’s not just about cavities, either. Oral health contributes greatly to the primary health of individuals. Poor oral health can contribute to poor overall health, exacerbating all diseases and illnesses, resulting in high medical bills and a negative impact on the quality of life.

The "Healthy People 2020" report identified oral health as one of the 10 leading health indicators, along with access to knowledge and treatments for nutrition, cancer, HIV, and heart disease. Good oral health contributes to the well-being of an individual that impacts the ability to speak, smile, smell and eat.

In a survey conducted by IHS, Native American children between three and five years old have three times the number of cavities that their White counterparts in the same age group have. Among Native Americans in the 35 to 49 year-old age group, untreated dental care is two-and-half times higher than their White counterparts.

To arrest these dismal rates, more dentists are needed in Indian Country. And not just any dentists who are taking jobs at IHS to pay off student loans.

We need more Native American dentists and dental students like Teague Rutherford — Indigenous people who want to grow up and treat citizens of their tribal communities with compassion, respect and a smile.

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

New Mexico Will Investigate Forced Sterilization of Native American WomenUSDA Expands Aid for Lost Farming Revenue Due to 2025 Policies

Two Feathers Native American Family Services Wins 2026 Irvine Leadership Award

Bill Would Give Federal Marshals Authority to Help Tribes Find Missing Children

Indian Health Service to Phase Out Mercury-Containing Dental Amalgam by 2027