- Details

- By Elyse Wild

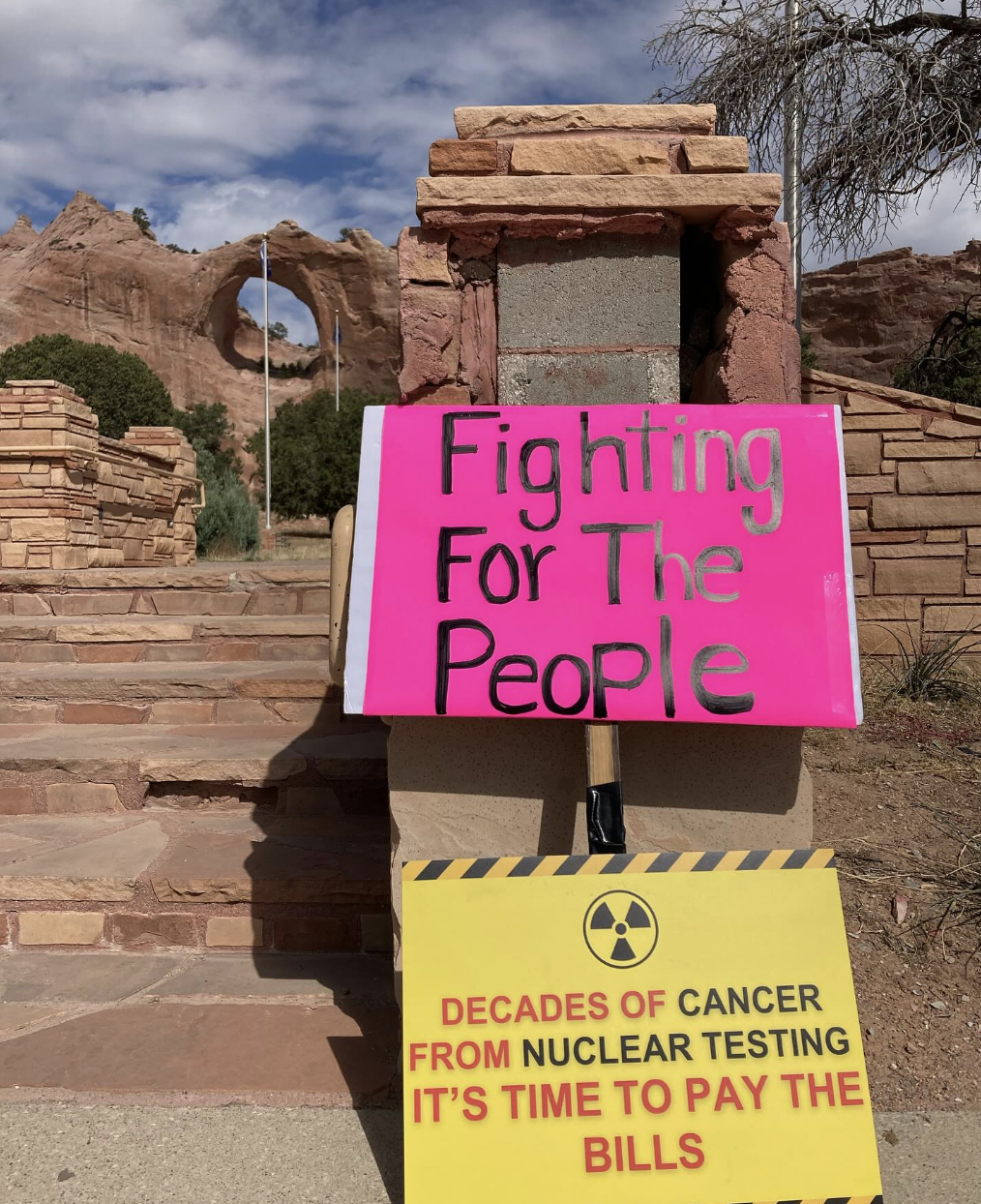

Victims of radiation exposure from federal uranium mining and nuclear testing on tribal lands in the Southwest could receive increased compensation under an expanded version of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act included in a major congressional spending bill.

The expanded RECA, sponsored by Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), was wrapped into the base text of "The Big Beautiful Bill" last week, offering hope to Native Americans who have sought broader coverage and higher payments for radiation-related illnesses.

For advocates in the Navajo Nation, where radiation exposure has driven high rates of cancer and terminal illness, the announcement was an emotional victory. But they say the path to justice remains long.

Lorie Sekayumptewa (Diné, Sac&Fox, Hopi), a member of the Diné RECA Sawmill Warriors, a grassroots advocacy group made up of radiation survivors in the Navajo Nation, learned of the expanded act being included in the spending bill during a call with Hawley the day before it was made public on Thursday, June 12.

"I cried on Zoom, but at the same time, we've heard that before, so we didn't get too excited," Sekayumptewa told Native News Online. "We still have tasks ahead of us because a lot of our Indigenous people here do not even know and do not connect their illnesses to this uranium history and legacy, and yet we're continuing to see our loved ones pass away."

For 40 years, the federal government mined uranium, a naturally occurring radioactive metal that fuels nuclear power, on the Navajo Nation. Nearly 30 million tons of uranium were mined on the reservation from 1944 to 1986, according to the Environmental Protection Agency — enough to fill the Empire State Building 12,000 times. The United States also conducted nearly 200 atmospheric nuclear weapons development tests in the Southwest from 1945 to 1962. Radiation exposure is linked to a range of serious illnesses, including kidney disease, various cancers and respiratory disease.

Congress approved RECA in 1990. The law provided compensation from $50,000 to $100,000 per individual for a range of illnesses, depending on which category applicants fell under — miners, on-site workers or downwinders. A bill that would have renewed and expanded RECA passed the Senate last March with a vote of 69-30. It then “went dark a year ago due to congressional inaction,” according to a statement from Hawley, who had called out Speaker Mike Johnson for the House’s failure to reauthorize and expand compensation funds.

Native communities and advocates continued to work in an effort to get RECA restored. The program paid out more than $370 million to Native people over three decades — around 13% of its total payout as of July 2024 — but according to some recipients and applicants, its limitations proved a burden, rather than relief.

And financial compensation under the program fell short of actual costs. Medical bills related to cancer treatment can exceed $150,000.

Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren called the list of diseases covered by RECA "woefully incomplete" in a public statement last June. Claimants had to prove that their disease could be directly linked to uranium exposure from mining or nuclear testing activities.

Sekayumptewa said that could mean searching through years of medical records, which might be sparse for remote Native communities in the Southwest, where access to care is a persistent barrier. If someone manages to collect sufficient proof, they typically did so under the duress of serious illness.

The revised act increases compensation amounts, expands coverage areas, covers a wider range of illnesses associated with radiation poisoning and extends the act until 2028.

Maggie Billman (Dinè) grew up in Sawmill, Ariz., a region located downwind of uranium mines and testing sites. Her father, a Navajo Code Talker who served in WWII, worked in the uranium mines and died of stomach cancer. She and her nine siblings have suffered various debilitating illnesses, from cancers to kidney disease.

“We're still losing family, relatives, neighbors all across the Navajo Nation from people being exposed,” Billman told Native News Online.

Sekayumptewa and Billman praise the improvements in the new legislation, but want the government to focus resources on providing healthcare to survivors.

Tribal members living on the Navajo Nation have few options for cancer treatment. The Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation opened a cancer center in 2019 — the first and currently only cancer treatment center on any Indian reservation. A community-based board of directors representing eight Navajo chapters, the Moenkopi Village on the Hopi Reservation and the San Juan Southern Paiutes governs the facility. For people living across the vast reservations, the drive to treatment might be 3 hours one way.

“The health part is the main thing,” Billman said. “My family doesn’t care about the money. They’re worried about their health. I've been saying that for a year, for a few years now, that we need better health care. “

More Stories Like This

Indian Health Service Reflects on 2025; Touts Facility Expansions, Workforce DevelopmentSenate Committee on Indian Affairs to Host Hearng in Bills to Beneift Tribal Health Programs

Cherokee Nation Plans Reentry Housing Using Opioid Settlement Money

Bipartisan Bill Seeks to Address Health Disparities in Tribal Communities

After Funding Whiplash, Feds Invest $100M to Fight Addiction