- Details

- By Monica Whitepigeon

CHICAGO – Art reflects and interprets the world at specific periods of time, which is all the more reason for contemporary Native art to be showcased and documented. As the Indigenous Futurism movement gains momentum, Native visual artists search for broader outlets and platforms to appropriately present their artwork.

Most well-known art museums and galleries that cater to Native arts are located in the Southwest or New York. Indigenous artists from the Midwest rely on major art venues outside Chicago, such as All My Relations in Minneapolis and Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis. Limited accessibility to mainstream institutions creates a disservice to urban Native experiences and audiences are not given opportunities to connect with those stories in public settings.

Three Chicago-based Indigenous Futurists, Debra Yepa-Pappan (Jemez Pueblo, Korean), Andrea Carlson (Grand Portage Ojibwe) and Santiago X (Koasati, Indigenous Chamoru from Guam) are actively working with and challenging institutions throughout the city to be more proactive when it comes to contemporary Native art.

“For those of us who know history and how colonizers have tried to exterminate us while convincing others that we’re only relevant in history, it’s important to change that narrative,” says Yepa-Pappan, Native Community Engagement Coordinator at the Field Museum.

Yepa-Pappan has made it her mission to connect as many Native voices as possible to the museum while its Native North American Hall undergoes renovations.

Having grown up in the city, Yepa-Pappan knows first hand the discriminatory practices, intentional or not, of Chicago institutions and has often had to showcase her work at national and international venues instead.

Her piece “Live Long and Prosper (Spock was a Half-Breed)” was created several years before the term Indigenous Futurism was coined, but it is now considered synonymous with the movement. Originally intended to be a fun sci-fi piece, Yepa-Pappan juxtaposed imagery from Edward S. Curtis and Star Trek while interjecting her dual identity. She believes the iconic Vulcan phrase “live long and prosper” is very encouraging and speaks to the Native experience.

“We’ve always done this,” says Yepa-Pappan. “We’ve always been thinking of the future. When talking about the future [nowadays], it’s all about space travel, but was that what our ancestors were thinking? Think about our present to ensure a better future.”

For Carlson, Chicago is a prime example of the necessity for Indigenous Futurism. As a highly segregated city, the city’s monuments and other memoriam often celebrate white settlers and restrict Natives to only historical contexts or as mascots.

“The erasure of Native people isn't just in our perceived absence, but in how we are represented and maligned,” Carlson explains. “Some people think that sports mascots, or romantic monuments of a historic Native person are equivalent to presence. But we are not in those images. Chicago, with all of its fantasies that lament us as a ‘disappeared race,’ is primed for a major shock with Indigenous Futurism, and it is the artists who are going to get us there.”

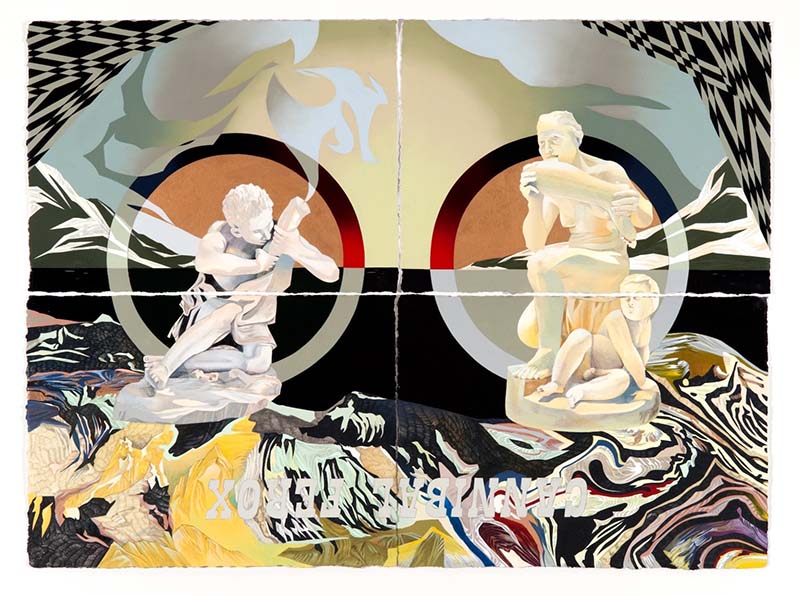

Cannibal Holocaust (2008)

Cannibal Holocaust (2008)  Cannibal Ferox (2009)

Cannibal Ferox (2009)

Calson’s “Cannibal Holocaust” and “Cannibal Ferox” purposefully reference cultural consumption within museum settings and act as metaphors for the relationships between collector and collected.

In 2019, the Art Institute of Chicago was under fire for its mishandling of extremely sensitive Native pottery and its lack of engagement with Native advisors. Since then, the museum made a gesture of good faith with a land acknowledgement event and reached out to Native community leaders.

“The Art Institute needs to wake up,” says Santiago X, a multidisciplinary artist who uses his architectural background to create innovative installations. “Indigenous art is like an action. I didn’t come into this to be an activist or protester, but here we are.”

Recently, Santiago X was commissioned by the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial, which focused on themes such as “No Land Beyond,” “Appearances and Erasures,” “Rights and Reclamations” and “Common Ground.” For his installation “HAYO TIKBA,” he created a traditional hut made of invasive non-indigenous plant species harvested from Chicago city streets, earth from sovereign tribal lands, projection mapping and spherical video.

HAYO TIKBA (THE FIRE INSIDE)

HAYO TIKBA (THE FIRE INSIDE)

Despite these efforts, Chicago institutions still have a long way to go when it comes to diversity and inclusion.

Ithaka S+R, a nonprofit organization that helps cultural and academic communities better serve the public, undertook a series of projects to devise a demographic breakdown of diversity data in professional museum roles. In its recent case study of the Museum of Contemporary Art, it found the museum is actively taking steps to diversify its collection. As well, 32 percent of its staff are people of color and POCs represent 26 percent of leadership roles. The museum partners with grassroots art organizations but has had trouble funding its internship programs, and there is a strong need for proper investments to grow and sustain these partnerships.

The study also revealed that “Chicago has the third largest creative economy in the U.S., generating an economic impact of over $2 billion a year, and employing over 150,000 people.”

In 2017, MCA unveiled its 50th anniversary exhibition titled “We Are Here,” a three-part collection of twentieth- and twenty-first-century art.

“The contemporary art market has become explosively expensive,” said MCA director Madeleine Grynsztejn. “And that is just one reason why we’ve widened our scope… to actively search out and acquire the work of artists in the Middle East, Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America.”

That same year at Arkansas’s Crystal Bridges Museum, Carlson participated in a Sotheby award-winning exhibition called “Art for a New Understanding,” which was billed as “the first ever survey of Native American artists of the 20th century.”

Yepa-Pappan believes there is a lot of work still to be done. “Until they change their exhibition and collective practices, they still treat us like we’re in the past,” she says.

In a publication for the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts called “The Earth is Our Mothership,” Carlson wrote, “Indigenous Futurisms are as much about healing in the present time and a process of truth telling found in reexamining our pasts, as it is about reimagining the future.”

Her feelings about the movement remain the same, now more than ever. “The work of Santiago X is so inspiring to me now,” she says. “I can't wait to see the spark of this movement grow into a fire, even if for transformative purposes alone.”

More Stories Like This

Vision Maker Media Honors MacDonald Siblings With 2025 Frank Blythe AwardFirst Tribally Owned Gallery in Tulsa Debuts ‘Mvskokvlke: Road of Strength’

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project and Partners at Ho’n A:wan Productions Launch 8th Annual Delapna:we Project

Chickasaw Holiday Art Market Returns to Sulphur on Dec. 6

Center for Native Futures Hosts Third Mound Summit on Contemporary Native Arts

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher