- Details

- By Monica Whitepigeon

CHICAGO—What would this country be like if Native people were never colonized? What if Native people weren’t always portrayed in the past or thought of as non-existent? How would future generations uphold Indigenous teachings and culture? These are only a few examples of themes that Native creatives and scholars explore through Indigenous Futurism.

Indigenous Futurism is a growing movement in—but not limited to—Indian Country, where Native peoples dare to reimagine societal tropes, alternative histories and futures through the exploration of science fiction and its sub-genres. This comes in a variety of mediums consisting of comics, fine arts, literature, games and other forms of media.

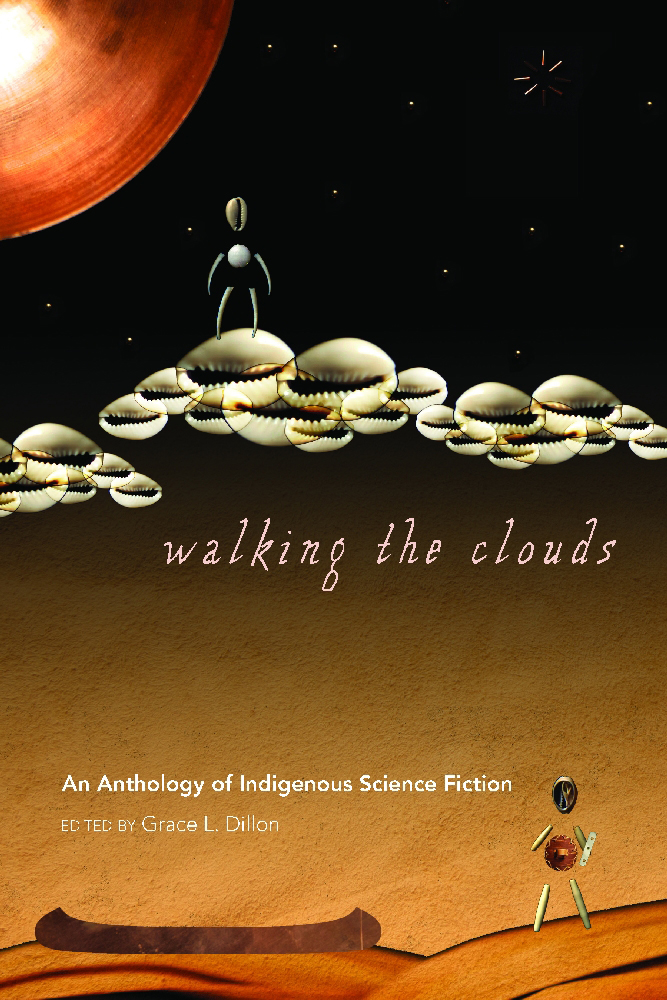

The concept was coined by Anishinaabe scholar Grace L. Dillon in her anthology of Indigenous writers from across the globe entitled “Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction.”

In the book’s introduction, she writes, “All forms of Indigenous futurisms are narratives of biskaabiiyang, an Anishinaabemowin word connoting the process of ‘returning to ourselves,’ which involves discovering how personally one is affected by colonization, discarding the emotional and psychological baggage carried from its impact, and recovering ancestral traditions in order to adapt in our post-Native Apocalypse world.”

The book features authors such as Leslie Marmon Silko (Laguna Pueblo), Gerald Vizenor, William Sanders and Stephen Graham Jones (Blackfeet).

Anishinaabe scholar Grace L. Dillon coined the term “Indigenous Futurism” in her anthology of Indigenous writers. Mainstream science fiction is sorely lacking when it comes to diversity, and more often than not, Native perspectives receive little to no inclusion.

Anishinaabe scholar Grace L. Dillon coined the term “Indigenous Futurism” in her anthology of Indigenous writers. Mainstream science fiction is sorely lacking when it comes to diversity, and more often than not, Native perspectives receive little to no inclusion.

In 2014, Vox interviewed University of California English professor Rob Latham and author Nalo Hopkinson, who criticized the sci-fi genre for its exclusivity.

“The standard excuse in science fiction is that in the future, there won't be any racism or classism, or we won't have any races because we'll all interbreed,” Hopkinson argued. “Those are really excuses for lazy characterization that erases ethnocultural specificities and differences in experience.”

Science fiction was developed in the 1930s by white men with scientific backgrounds, many of whom wrote for pulp magazines. This narrowed the definition of science fiction and left little room for non-white voices and women within the genre, despite the fact that some of sci-fi’s most common themes involve exploration and conquering.

“To the writers of the 1930s and 1940s, conquering a new world was a doctrine of manifest destiny. Conquering a new world means something different to people who were brought to the country in chains or were displaced or subject to genocide,” Latham told Vox.

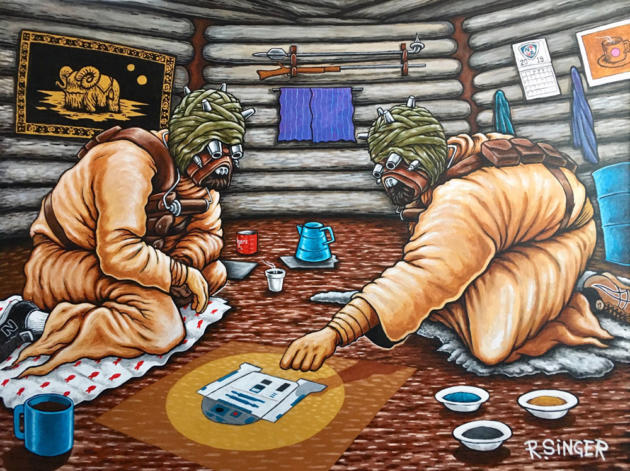

Diné artist Ryan Singer’s “Sand People, Sand Painting”depicts characters from the “Star Wars” movies inside a Navajo hogan, taking part in a traditional healing ceremony. The work is part of an online exhibit called“Indigenous Futurisms: Transcending Past/Present/Future” at The IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. (Photo via Facebook).The realities and rejection of Native history still affect people today. Native people often find themselves in reactive positions of social injustice while Indigenous Futurism gives power back to their voices and how they view the world.

Diné artist Ryan Singer’s “Sand People, Sand Painting”depicts characters from the “Star Wars” movies inside a Navajo hogan, taking part in a traditional healing ceremony. The work is part of an online exhibit called“Indigenous Futurisms: Transcending Past/Present/Future” at The IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. (Photo via Facebook).The realities and rejection of Native history still affect people today. Native people often find themselves in reactive positions of social injustice while Indigenous Futurism gives power back to their voices and how they view the world.

Recently, America was forced to reexamine what it considers to be normal behavior and how to be more socially conscious or “woke.” This country was born out of oppression and racism, which silenced millions of Native and African-American perspectives for centuries but could never fully extinguish them. This year, there were many successful solidarity protests and boycotts that caused significant changes for Native people, such as the renaming of sports teams, removal of oppressive statues, and other retired racist imagery.

Skeptics of this woke movement believe this to be an erasure of American culture and heritage, instead of viewing this as a correction of one-sided histories –– history that was never complete. Representation matters, especially in relation to pop culture. Stereotypical imagery only adds to misconceptions and furthers racist overtones.

In 2018, Marvel’s box office hit “Black Panther” proved that the world was ready to see strong Black superheroes in a fictional country known as Wakanda, a land untouched by colonialism and where fantastic, futuristic technology flourishes. It is the most successful example of Afrofuturism, a movement that has inspired Indigenous Futurism, and lays the ground work for other non-white cultures and alternative realities to be showcased to a broader audience.

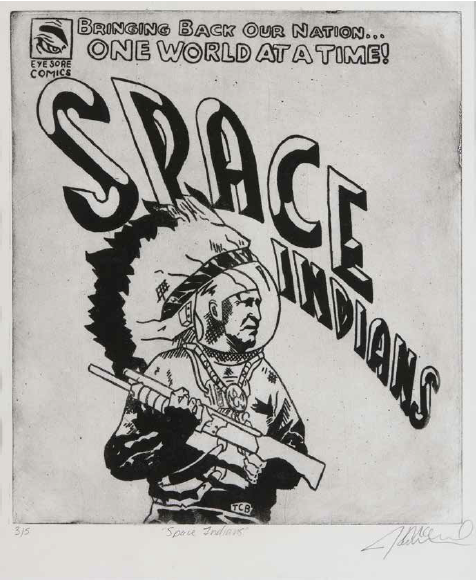

Paiute artist James McCloud’s “Space Indians” stems from his love of movies, comics, pop culture and family. The work is based on a photo of his great grandfather “sans space suit” he writes in a description of the piece, which is part of the IAIA’s online exhibit. (Via Facebook)Conversations around Indigenous Futurism continue to gain momentum through various platforms and more acts of social justice solidarity.

Paiute artist James McCloud’s “Space Indians” stems from his love of movies, comics, pop culture and family. The work is based on a photo of his great grandfather “sans space suit” he writes in a description of the piece, which is part of the IAIA’s online exhibit. (Via Facebook)Conversations around Indigenous Futurism continue to gain momentum through various platforms and more acts of social justice solidarity.

Detroit’s annual Allied Media Conference, which caters to social justice issues and community activists, says the “2020 edition will be a space for engaging with the ideas and practices our world needs most right now: media for liberation, collective care, abolition, Black and Indigenous futurism, and more.”

The IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts currently features the exhibit “Indigenous Futurisms: Transcending Past/Present/Future.” Artworks focus on science, Indigenous cosmology and how tribal oral history can be used to emphasize the importance of Native futurism, as well as ways to heal from trauma.

The exhibition runs until Jan. 2021, with a 3D virtual tour option and features contemporary artists such as Ryan Singer (Diné), Elizabeth LaPensée (Anishinaabe/Métis), Skawennati (Mohawk) and Santiago X (Coushatta/Chamoru).

More Stories Like This

Watermark Art Center to Host “Minwaajimowinan — Good Stories” ExhibitionMuseums Alaska Awards More Than $200,000 to 12 Cultural Organizations Statewide

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Takes Top Emerging Artist Apprentices to Phoenix for Artistic Exploration and Cultural Immersion

From Dishwasher to Award-Winning Chef: Laguna Pueblo's Josh Aragon Serves Up Albuquerque's Best Green Chile Stew

Rob Reiner's Final Work as Producer Appears to Address MMIP Crisis

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher