- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

More than 116,000 Native American ancestors are in limbo—their remains not yet laid to rest, but instead kept in storage at museums and institutions across the country.

That’s despite a 30-year-old federal law Congress passed to ensure institutional return of human remains and sacred objects, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Back in 1990, NAGPRA required all federal agencies and museums receiving federal funding (excluding the Smithsonian Institute which follows its own repatriation process and includes nearly two dozen museums and research facilities) to catalogue the Native American remains and cultural items held in their collections within five years. The law then required museums and agencies to notify tribes on its specific holdings affiliated to the tribe.

But a loophole in the law allowed the majority of the total human remains catalogued —those without documented tribal affiliation, deemed “culturally unidentifiable”—to fall through the cracks. Though museums and agencies still had to report those remains, they didn’t have to return them—yet.

“The law itself is written to make it pretty simple to affiliate, it’s just that institutions are choosing not to,” said Veronica Pasfield, a NAGPRA officer for her own tribe, Bay Mills Indian Community. Since 2010, she was a part of an intertribal group that will return approximately 2,200 ancestors back to their Michigan tribes. She said that institutional control within the law, a lack of real consequences and selfish motivations disincentive museums from returning the human remains they have in their inventory.

Now, the branch of government that administers NAGPRA compliance, the Department of the Interior — with weigh-in from tribal communities— hopes to right that wrong by revising NAGPRA rules for the first time ever.

“We know where they’re from”

Since 2010, NAGPRA regulations have provided a process for museums and institutions to return culturally unidentifiable Native American human remains, but the vast majority of museums have chosen not to.

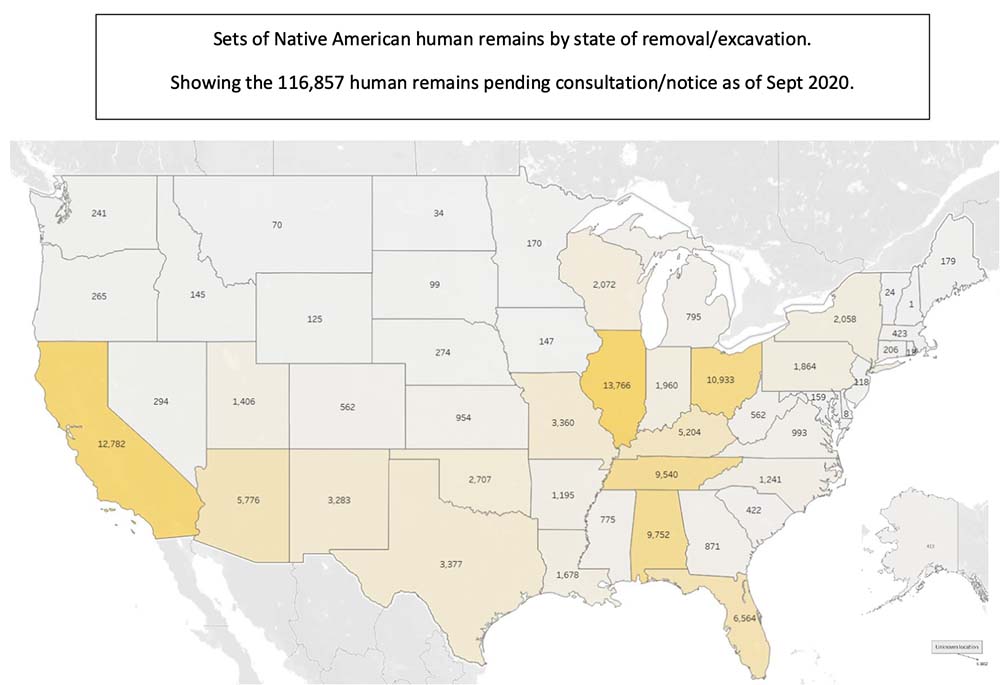

For the last five years, national NAGPRA program manager Melanie O’Brien has been organizing and visualizing the departments’ data on the remaining 116,857 human remains kept in museums and institutions across the country, not including the Smithsonian Institute’s museums and research facilities.

For the majority—90 percent —O’Brien said records show where the ancestors originally came from, “at least by state, if not by specific county or site.” Only 5% of the human remains were reported as coming from an “unknown” geographic location. The remaining 5% of the human remains are culturally affiliated, but institutions have not yet published a Notice of Inventory Completion that would effectively allow affiliated tribes to claim their ancestors.

Among the proposed changes to the regulations, the one with the largest impact swaps out “culturally unidentifiable” for “geographically affiliated,” matching the known geographic origins of each set of human remains to a present day tribe.

“I think it’s pretty simple,” Melanie O’Brien told Native News Online. “For most of these (human) remains we know where they're from. And... I think that most tribes have pretty specific territories of ancestral occupation.” The geographic information isn’t new, she said. It was reported by museums and agencies in 1995. They just weren’t required to repatriate the human remains previously.

Now, museums and institutions will have a ticking clock to complete their work.

“What the revisions do is say that a museum has to make updates in two years, and publish a notice six months later,” O’Brien said. “So that all of the human remains that come from known geographic locations would be available for tribes to request repatriation. There's no timeline or schedule for the tribes to make those requests. That would be dependent on the tribes.”

72 percent

Despite the absence of a mandate to geographically affiliate, 28 percent of museums and federal agencies with Native American remains in their collections have finished their repatriation work voluntarily by geographically affiliating the human remains left in their inventory. The Denver Museum of Nature and Science is one of them, O’Brien noted.

But the remaining 72 percent of institutions have lengthier regulatory processes and extensive consultation processes. Some Native leaders say there’s even more sinister reasons for holding onto human remains, such as monetary incentives and status tied to research.

The Association on American Indian Affairs, a nonprofit founded in 1922 to protect Native American sovereignty and culture, publicly criticized the Harvard Peabody Museum (the institution with the second largest Native human remain inventory in the country) for its repatriation practices this year when Harvard announced it found the remains of 15 possibly formerly enslaved African Americans in its collection.

In a letter to the museum, AAIA director and attorney Shannon O’Loughlin (Choctaw) noted the Peabody only completed repatriation for 18.4% of the ancestors in its collection. “That means there are still 6,586 of our Ancestors and 13,610 of their burial belongings in boxes on shelves,” she wrote. “You have significantly more deceased Native people in boxes on your campus than the number of live Native students that you allow to attend your institution.”

O'Loughlin also demanded the museum stop research on the Native American human remains in its collection.

In response, Museum director Jane Pickering and Harvard history professor Phil Deloria (Standing Rock Sioux) wrote to O’Loughlin that the Peabody does “not allow destructive research on culturally affiliated human remains or items without permission from the tribe.”

“So the omission there is that they are researching culturally unidentifiable ancestors,” O’Loughlin said. “Research ...is absolutely going on. It helps promote the marbled floors and the high ceilings of academia. It helps create peoples’ careers and their dissertations and their published works. And there's still people that very much believe that their unilateral exploration and research without any tribal involvement is absolutely their right.”

Deloria did not respond to Native News Online’s request for an interview.

NAGPRA compliance “is the floor”

Leaders and staff from two of the museums with the largest holdings of Native remains—the Ohio History Connection in Columbus, Ohio, and the Illinois State Museum in Springfield, Illinois—told Native News Online that lack of Native representation among staff, understaffing, and a Western read of the law have all led to institutions like theirs meeting the bear minimum NAGPRA requirements.

“The spirit of the law is really what’s important, and it's supposed to have ongoing (tribal) consultation, and that became quite irregular here...as a result of ...institutional priorities just weren't aligned,” said Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, Illinois State Museum director. The institution she runs has the fifth largest collection of Native ancestors in the country at 7,587 human remains (94 percent of which are linked to tribes within the state’s borders, Catlin-Legutko said). The director previously worked to decolonize the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, Maine—where she served as president—by developing protocols to engage the local Wabanaki tribes. “There was compliance happening here with NAGPRA, but compliance with NAGPRA is quite frankly minimal. It’s the floor or what we need to do.”

Over the last 30 years , the National Parks Program collected a total of $59,111 in civil penalties from institutions failing to comply with NAGPRA, though O’Brien said the dollar amount doesn’t reflect enforcement.

Alex Wesaw (Pokagon Potawatomi) is the Director of American Indian Relations at the Ohio History Connection. The museum has 7,166 Native American remains, and 110,276 associated funerary objects, according to the updated inventory listing on the National Park Service’s website. It is number three on the list of entities that hold the largest number of ancestral human remains, behind Berkely and the Peabody Museum.

Wesaw said that, until about five years ago, the Ohio History Connection (previously the Ohio Historical Society) did not have an American Indian staff position.

“The institution was frankly doing the best that it could at the time...but I don't know that there were any Native staff members to have their voice heard in this process,” he said. “Having Indigenous people on staff, we're able to understand the importance of culturally affiliating the ancestors we’re caring for.”

In the last two years, the museum hired Ben Garcia to lead as the Deputy Executive Director and Chief Learning Officer at the Ohio History Connection. Garcia came from the San Diego Museum of Man, where he helped the organization “turn towards its NAGPRA work” and rethink its displays of human remains. He said he came to Ohio to help the Ohio History Connection do the same.

Garcia pointed to narrow, western western interpretations of the law as a reason institutions have been slow to repatriate culturally unaffiliated ancestors.

In order for a museum to make a cultural affiliation determination between a tribe and human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects or objects of cultural patrimony, all of the following requirements must be met: an identifiable present-day federally recognized tribe; an identifiable earlier group; and a shared group identity that can be reasonably traced between the present-day Indian tribe and the earlier group.

If museums prioritized tribal consultation and indigenous knowledge in doing this work, repatriation of all human remains could have happened a lot quicker, Garcia said.

“But because most of these institutions were looking for evidence that didnt come from sources of Indignous knowledge, they were looking for evidence that came from western ways of understanding these concepts, it went slowly,” Garcia said. “The slowness has been about the academy, the scientific world, the political world, coming around to understand that traditional scientific ways of building knowledge or identifying evidence don’t ... make sense for all communities and all situations.”

The Ohio History Connection has begun its work to decolonize by hiring a full time employee dedicated to NAGPRA, developing an American Indians Relations policy outlining how it will interact with tribes moving forward, and engaging the 45 tribes that are geographically affiliated with the human remains in the museum’s collection.

Garcia said he hopes the new NAGPRA regulations come with a funding mechanism, not just for museums to hire more staff, but for tribes, too.

“Part of the challenge timewise can get addressed with new staff, but then another part of it is really about the fact that it's not just museums that are under-resourced in this area, but tribes, as well,” he said. “You have a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer who is usually just inundated with many different functions at work. So, what I would hope to see are federal resources going to tribes directly, to help increase capacity within tribes to do this work.”

Planning for a new process

As for the path forward with NAGPRA, the Department of Interior received final comments from tribes and advocates on Sept. 30.

The process from there will depend on the feedback they’ve received, O’Brien said.

”The department is committed to taking that input and the comments from Indian tribes and Native Hawaiians and then making the next decision,” O’Brien said.

O’Loughlin told Native News Online that AAIA has proposed a different process entirely.

“I don't think the changes are where they need to be,” O’Loughlin said. “But the idea that we can eliminate this CUI [culturally unidentifiable] category and actually do the work of what Congress intended, which was to repatriate, not to allow museums a huge loophole to deny tribes...it’s a much better system.”

Still, she said, museums have too much decision making power and not enough follow through.

“We want to take the current CUI inventories and not let the museum make any determinations on them, and hand them over to the committee and the Secretary for repatriation,” she said. “The museums had a chance to do the right thing and consult properly and repatriate, and we want to propose something that takes that decision making out of their hands in order to fulfill congressional intent with the statute

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsColusa Indian Energy Participates in Port of Quincy Town Hall on Columbia Basin Power Project

Q&A: Jingle Dress Dancer Answered Call to Ceremony in Face of ICE Violence

Haaland Gets First Hand Look at Efforts to Address Homelessness in Albuquerque

Navajo Nation Secures $285 Million in Federal Broadband Funding to Connect Thousands of Homes

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher