- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

LOS ANGELES — On the 76th anniversary of the liberation of Nazi Germany’s Dachau Concentration Camp, a Jewish human rights center based in Los Angeles is celebrating a Native American soldier of Chikasaw and Choctaw descent for his assistance.

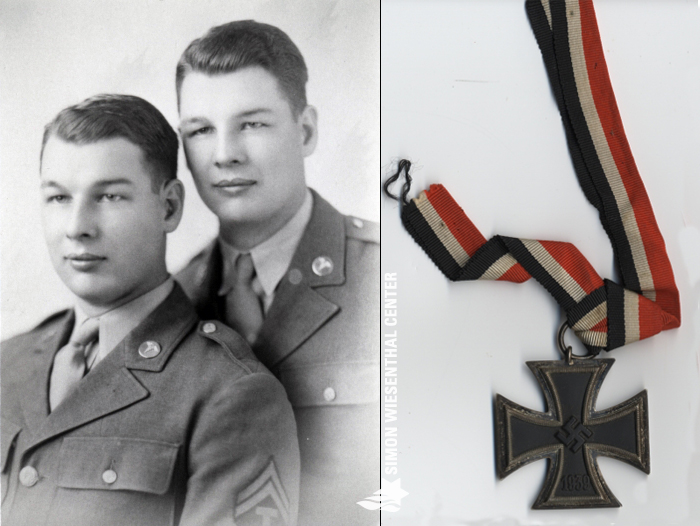

Twin brothers Bennett Freeny and Benjamin Freeny—born in 1922 in Caddo, Okla.—enrolled in the U.S. Army as 18-year-olds, both serving as combat medics, according to information provided by the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

The boys were enrolled in the 45th Infantry Division, a regiment of the United States Army's National Guard also known as the Thunderbird Division, consisting of 14,500 troops, including more than 1,500 Native Americans. The group was composed of soldiers from the American Southwest, and thus bore the symbol of a Native American Thunderbird, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

The Thunderbirds fought battles in North Africa, Italy and France between 1943 and 1944. In 1945, the final year of World War II, the Thunderbird Division captured the German cities of Nuremberg and Munich.

Bennett Feeny was part of one of the first units to enter Dachau Concentration Camp on April 29, 1945, where they helped liberate tens of thousands of prisoners. His brother, Benjamin Freeny, was killed in combat in Italy two years earlier, according to the Center’s archivist.

More than 11,000 Jews were killed at Dachau—the first Nazi concentration camp established in March 1933, shortly after Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany—through starvation.

According to the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s press release, Bennett Freeny stripped a German officer of an iron cross, or military decoration, after the liberation.

A fellow soldier, Ace Caldwell, detailed the account in a letter sent to Freeny’s daughter, a copy of which she later gave to the Center to keep in their archives.

“Bennett and I were both medics with the 45th and we encountered a great many prisoners who had contracted Typhoid and other ailments, and even more who had been starved,” the letter, quoted by the Center, reads. “We were very disheartened by the condition of these poor souls and still enraged by the evil and carnage we had encountered liberating the camp.”

He goes on to say that a German SS officer walked through the camp with “a sort of sneer on his face.”

“Your dad stood, walked up to him and pulled out his knife,” Caldwell wrote. “A couple of our boys stood by and prevented the officer from moving. Your father, one at a time, cut his medals and insignias off his uniform – Death Head, Edelweiss insignia, various patches and came to the Iron Cross hanging around his neck. Bennett grabbed it, cut the ribbon, and said ‘this is the sign of a hero – there are no heroes here’ and stuffed all the medals and patches in his pocket. A few of the prisoners who were able, clapped. We were young men who had a lifetime of horror and violence visited upon us by age 23. None of us would ever be the same, but that day your father was bigger than life.”

Three of the handful of Congressional Medals of Honor that American Indians received in World War II were awarded to soldiers in the 45th: Ernest Childers, Jack Montgomery, an Oklahoma Cherokee and classmate of Childers at Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, and Van T. Barfoot, a Mississippi Choctaw, according to American Indian Magazine.

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsNavajo Nation Mourns the Passing of Former Vice President Rex Lee Jim

Deb Haaland Earns Endorsement From Communications Workers of America Local 7076

University Soccer Standout Leads by Example

Two Native Americans Named to Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee's“Red to Blue” Program

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher