- Details

- By Kaili Berg

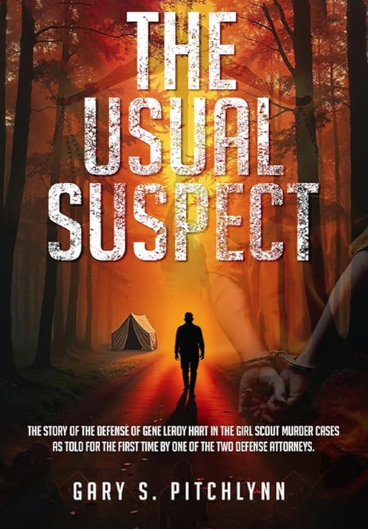

In his book "The Usual Suspect," Oklahoma attorney Gary Pitchlynn (Choctaw) shares his story from one of the state's most shocking murder trials, the 1977 Girl Scout murders at Camp Scott.

The book gives an inside look at Pitchlynn's role defending Gene Leroy Hart, a Cherokee man accused of killing three young girls. It also shines a light on flaws in the justice system.

In 1977, the quiet of Camp Scott was shattered when Lori Farmer, Doris Milner, and Michele Guse were found murdered. The public was horrified, and investigators quickly focused on Hart.

Though he had prior convictions and had escaped prison, many Cherokee people felt he was unfairly targeted due to prejudice against Native Americans.

Pitchlynn, fresh out of law school, and experienced attorney Garvin Isaacs were chosen to defend Hart. The trial became intense, filled with media attention and questions about police work and fairness.

Pitchlynn writes about moments in court that showed problems with the case, including weak evidence and a judge who seemed to favor the prosecution.

Pitchlynn also describes visiting Cherokee Medicine Men during the trial for support and clarity. Eventually, the jury found Hart not guilty, but he returned to prison for past crimes and died there two years later. The Camp Scott murders remain unsolved.

Now a veteran lawyer, Pitchlynn serves as Attorney General for the Absentee Shawnee Tribe and Associate Judge for the Quapaw Nation Tribal Court. He has spent over 45 years fighting for tribal nations and Native rights in Oklahoma.

In a recent interview with Native News Online, Pitchlynn reflects on his early career and his role defending Gene Leroy Hart in the infamous 1977 Girl Scout murders case. Pitchlynn details major flaws, including planted evidence and prosecutorial bias, and the spiritual guidance provided by Cherokee medicine men during the trial.

Editor's Note: This article has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Can you tell me a little about yourself and what drew you into practicing law?

I went to the University of Oklahoma for journalism, did graduate work there too, then went to law school at Oklahoma City University. For almost 47 years, I’ve primarily practiced federal Indian law, working for tribes, tribal organizations, and Native people. I started as a criminal defense lawyer.

This book is about my first murder case, which came less than a year after finishing law school

It was a huge regional story with lots of publicity. Several generations now aren't familiar with it.

I wrote the book to tell the story of how we handled the case and got an acquittal for our client despite public doubt.

What were your first impressions of the case, and did you realize then how big it would become?

I knew right away it had a lot of publicity, three little Girl Scouts were killed. But I didn’t realize just how big it would become nationally.

I got involved through a nonprofit that gave legal advice to Native people. I brought a friend, thinking we’d just advise the guy and he’d get a high-profile lawyer. We knew it would be big, but didn’t expect it to explode like it did.

Even early on, we were skeptical. They were talking about our client within an hour of finding the bodies. That raised red flags. As we got to know him and his family, our skepticism only grew.

You detail major flaws in the investigation and trial? what stood out the most to you as unjust?

Catching law enforcement planting evidence was probably the most shocking. We also believe the forensic chemist manipulated slides to falsely tie our client to the crime scene. The overt cheating and lying by investigators was the worst.

The judge also favored the prosecution, letting in improper testimony. But the manipulation of evidence was the most egregious.

What role did Cherokee Medicine Men and cultural guidance play in your defense approach?

I didn’t grow up with much traditional medicine knowledge, I was raised more like a white kid by my mom. But we met with a medicine man who warned us that evil medicine was being used against us and our client.

He gave us cigarettes and instructions to protect ourselves spiritually. One even smoked the courthouse during trial to keep evil out. Our client’s family believed deeply in these medicine men, who they’d relied on for generations.

What does this case say about how the justice system treats Native defendants, then and now?

Not much has changed. If you're a person of color, tribal, Black, Latino, the system tends to swallow you up. It takes money and resources to defend properly.

Mr. Hart got lucky because two young, idealistic lawyers (us) saw injustice and fought back. We had volunteers who believed in the case. Without them, we couldn’t have done it. The system can work, but only when pushed hard by bold, aggressive advocacy.

Why did you decide it was time to share this story through "The Usual Suspect"?

My friend Garvin and I talked for years about telling our side. Other books and documentaries always told it from law enforcement’s view, often blaming the jury for getting it wrong.

Seeing recent documentaries recycle that version pushed me to write. During the pandemic, I started outlining and writing. I wanted to make sure our perspective, the defense story, was finally told.

What do you hope readers take away from this case and your experiences?

For young Native lawyers, I hope they take away the need to be bold and aggressive in criminal defense work. Sometimes you have to toe the line between proper conduct and contempt to fight for your client.

For general readers, I want them to understand this system isn’t perfect. It requires aggressive advocacy to make it work fairly.\

How did this case shape your career and worldview going forward?

Winning this case opened many doors. I had offers to take on big cases nationwide, but I stayed local because of family.

After about 10 years, I shifted to federal Indian law so I could help tribes in a bigger way. I played a big role in tribal gaming expansion from the late 1980s through the 2000s. That work aimed to raise the standard of living for tribal communities.

What advice would you offer to young Native attorneys today facing tough or controversial cases?

Fight for your client, even if it puts your career at risk. Be bold. Judges may threaten contempt, wear that as a badge of honor. Don’t be afraid of the system. It only works fairly when lawyers push it to.

More Stories Like This

Watermark Art Center to Host “Minwaajimowinan — Good Stories” ExhibitionMuseums Alaska Awards More Than $200,000 to 12 Cultural Organizations Statewide

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Takes Top Emerging Artist Apprentices to Phoenix for Artistic Exploration and Cultural Immersion

From Dishwasher to Award-Winning Chef: Laguna Pueblo's Josh Aragon Serves Up Albuquerque's Best Green Chile Stew

Rob Reiner's Final Work as Producer Appears to Address MMIP Crisis

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher