- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

LOS ANGELES — What would possess a woman to fashion the face of Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, with thousands of tiny seed beads?

“I love the accent. He sounds exactly like my dad. My dad is from Brooklyn,” said Tlingit artist Corey Stein. “My dad was patient and could explain things well like Fauci. The first time I heard Fauci speak, many years ago, his mannerisms were just like my dad’s and they both had the same Brooklyn accent.”

Stein is also mad about Fauci because nothing makes him mad.

“I like how calm he is. I wish I could be like that,” she said. “He never raises his voice. I love people who don’t get mad.“

Tlingit artist Corey Stein used flesh-toned silk strips for the back of her beaded Fauci face mask. (Larry Lytle)

Tlingit artist Corey Stein used flesh-toned silk strips for the back of her beaded Fauci face mask. (Larry Lytle)

Stein’s Fauci infatuation was rekindled in March, when she once again heard the infectious disease specialist’s now-ubiquitous accent and witnessed his dignified demeanor during the White House Coronavirus Task Force briefings. Having found a new muse, Stein felt moved to bead a portrait of the famous doctor.

Within about two weeks of starting her Fauci mask, Stein was done with the rectangular beaded portrait, which she modeled on an image of Fauci she found online.

“It’s like an appetizer instead of a big beaded piece that takes a long time,” Stein said.

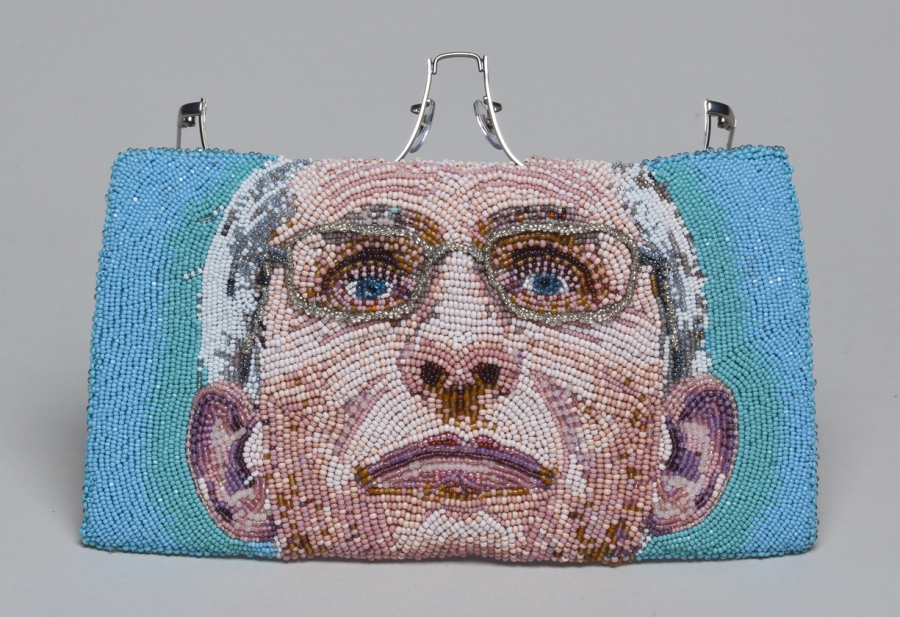

Mainly composed with a spectrum of blue, silver and flesh-colored beads, the mosaic-like mask displays a serious and focused Fauci. But there is also an air of impishness in the brilliant blue eyes sparkling with kindness and humor from behind silver spectacles.

“I love the blue eyes,” Stein said. “That photo I found was great because it had a blue background. With all my beadwork I work from a photo that I Xerox onto typing paper and sew onto felt.”

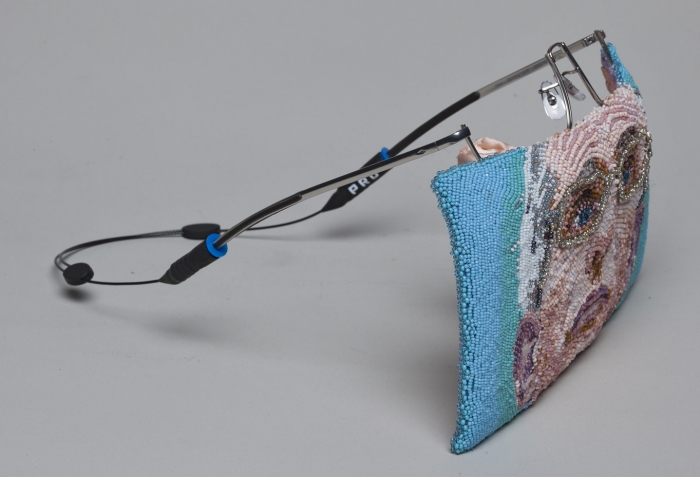

Keeping with the spirit of Fauci, Stein further sewed on parts of actual silver eyeglasses to complement the pair Fauci sports in the beaded design.

“I took a pair of silver glasses and cut the top off, so you wear it like it's a pair of glasses,” Stein said.

The back of the mask shows the sensual side of Stein’s Fauci fascination.

“The inside of the mask is sexy,” she said. “I lined it with different shades of satin. Every flesh-colored satin I could get a hold of.”

When Stein began beading Fauci, she had an accessory other than a mask in mind for him.

”Originally I wanted to do a pouch—a ‘Fauci Pouci’—like a beaded clutch you could put your sunglasses or opera glasses in,” she said. “A bag for going to the opera with Fauci.”

Tlingit artist Corey Stein attached parts of a pair of glasses to her beaded Fauci face mask to reference the glasses he wears on the mask. (Larry Lytle.)

Tlingit artist Corey Stein attached parts of a pair of glasses to her beaded Fauci face mask to reference the glasses he wears on the mask. (Larry Lytle.)

Stein decided Fauci was a better fit for a face covering than a fancy purse when she came across the Breathe Facebook group. Breathe has been a showcase for artistic face masks made by Indigenous designers since the start of the pandemic, and has grown to more than 2,000 members. Stein said she plans to post a picture of the Fauci mask on Breathe, and enter it in the group’s mask contest.

The majority of the masks on Breathe are rich with traditional tribal patterns and details, and incorporate ancient techniques passed down through generations.

Stein is self-taught. Her Fauci mask, which is more influenced by her father’s New York roots than her mother’s Tlingit identity, will be a bit of a departure from the rest of the group’s pieces.

“Nobody ever taught me the traditional way,” Stein said. “I know [how to bead] from going to museums and copying people, and going to potlatches and things where you see art and ask, ‘Can you show me how to do that?’”

Tlingit artist Corey Stein modeling the Fauci face mask she created with thousands of seed beads. (Larry Lytle)While beading is one art that Stein took on without formal or traditional training, she has studied and practiced art forms like animation and sculpture at the California Institute of the Arts and the Rhode Island School of Design. And though there’s nothing in the process or pattern of the Fauci mask that directly points to Stein’s Tlingit heritage, all of her beadwork is bound to Alaska. Her mother’s hometown is at the heart of her bead art.

Tlingit artist Corey Stein modeling the Fauci face mask she created with thousands of seed beads. (Larry Lytle)While beading is one art that Stein took on without formal or traditional training, she has studied and practiced art forms like animation and sculpture at the California Institute of the Arts and the Rhode Island School of Design. And though there’s nothing in the process or pattern of the Fauci mask that directly points to Stein’s Tlingit heritage, all of her beadwork is bound to Alaska. Her mother’s hometown is at the heart of her bead art.

“We used to go up to Wrangell every few years in the summer to visit my relatives. One year I went with my cousins for a totem raising, and that's when I saw some really cool beaded barrettes in the drug store made by a local artist,” Stein said. “I bought two and copied from them. Whenever I'd see some I liked I'd buy them and copy again, as well as bead work I'd see in museums and fairs.”

Years of recreating ultimately resulted in a modern artist who beads to the beat of her own drum, and consistently impresses colleagues and collectors at art shows.

At the beginning of March, shortly before events started getting canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Stein won a Judges’ Choice Award at the Heard Museum Indian Market in Phoenix for her beaded portrait of artist Jennifer Celio.

“I was totally psyched because I got the award,” Stein said. “I was excited to make more work.”

As soon as she got home to Los Angeles, Stein started “working like crazy” on a big beaded piece-in-progress depicting her and an ex-boyfriend decades ago at an arts district in Santa Monica.

As she beaded the nostalgic scene, and as the ever-worsening news of COVID-19 went on around her, a familiar and appealing accent entered her ears. Not long after, she decided to press pause on the project and pursue the beaded Fauci mask.

Stein’s affection for Fauci goes beyond him simply being “a calm guy with a Brooklyn accent.” She also admires his endless efforts to fight the deadly virus.

“Many of my friends died from AIDS back when nothing could be done. Fauci was working on the cure back when his hair was dark. Now at least there are things we can do about it, no cure yet but at least there are medications to slow it down,” she said. “The other thing about Fauci is he could be kicking back and retiring but no, he's still looking for a cure.”

Though the mask is complete, Stein isn’t finished with Fauci as a subject just yet. She’s ready to bead another Fauci face covering based on the baseball cards capturing the doctor throwing the first pitch on the opening day of the MLB season in July.

“I want those baseball cards,” Stein said. “Maybe I should make a mask of him pitching in a mask.”

More Stories Like This

Two Indigenous Group Exhibits Opening January 9, 2026 at WatermarkWatermark Art Center to Host “Minwaajimowinan — Good Stories” Exhibition

Museums Alaska Awards More Than $200,000 to 12 Cultural Organizations Statewide

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Takes Top Emerging Artist Apprentices to Phoenix for Artistic Exploration and Cultural Immersion

From Dishwasher to Award-Winning Chef: Laguna Pueblo's Josh Aragon Serves Up Albuquerque's Best Green Chile Stew

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher