- Details

- By Alexandra Blye and Karen Middleton

Haskell Institute, founded as United States Indian Industrial Training, was an Indian boarding school in Lawrence, Kansas that was established in 1884. During the boarding school era, children were brought there by force — sometimes in child-sized handcuffs — and put into a re-education program. The legacy of the boarding school era still resonates today.

This article was produced in collaboration with the Native Storytelling Workshop at the University of Kansas.

The early years of Haskell brought death to Native children, who were taken from the Kickapoo, Cheyenne, Omaha and several other tribes. Many of these deaths were caused by poor conditions such as incomplete dorms, bad restroom facilities, and diseases spread by students sharing towels. If a student was sick, they were sometimes sent to the hospital.

Yet, food rations in the hospital were stolen by the head doctor, and being sold in nearby Lawrence. Some rations meant for the children were also being taken by the nurses.

“They were starved,” Travis Campbell, property management specialist at Haskell, told Native News Online. Campbell gives tours and shares the history of the institution. Sick students had little access to medication, because the head doctor was also stealing the medication provided by the government, and selling it in Lawrence as well, to other physicians.

“It was just deplorable,” Campbell said. Students as young as three were being ripped from their families and brought to Haskell for what was intended to be a four-year education but most times ended up being longer–some ended up staying for 10 years. Some parents of the children willingly sent their children to Haskell, while others were forced or convinced by the government to send their children to Haskell.

Native families were told that Haskell was the best opportunity for their children; other families had food rations, clothing rations, and important supplies taken away by the government until they sent their children to Haskell. Most of the time children were not allowed to leave or return home to see their family, however there are a few records of students being allowed off campus to see their family on these visits.

“So imagine your child is taken from you at the age of three. And they're allowed to come back two or three years later, and spend a week and then go back to school,” Campbell said.

There are cases of children running away from Haskell, and sometimes when they were sent to visit their family, they did not return. People would hide the children and cover for them so they would not be found. Runaways couldn’t always find help because it was illegal to harbor the runaways and not notify the boarding school or the authorities.

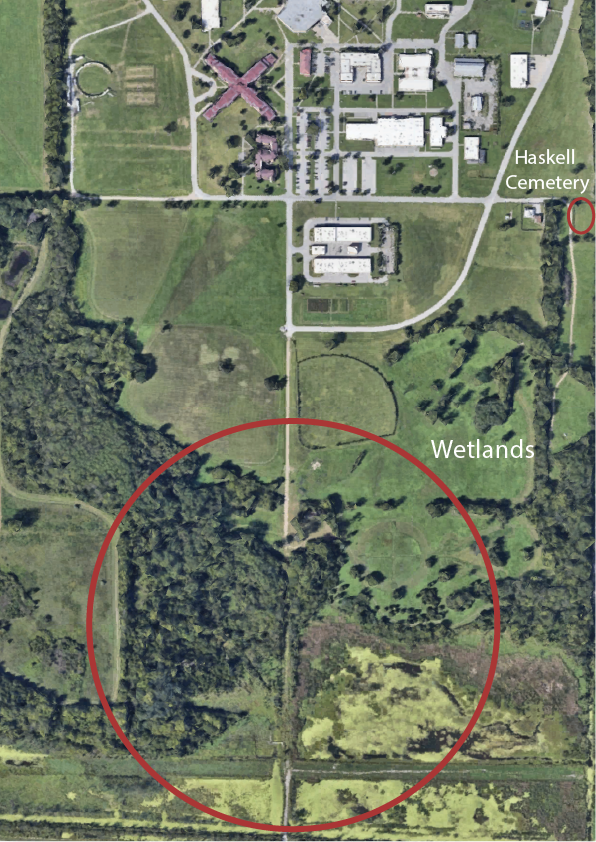

A map of Haskell's grounds, showing the route children would take when they would run away. (Kristen Middleton)

A map of Haskell's grounds, showing the route children would take when they would run away. (Kristen Middleton)

Today, there is a cemetery for some of the children that died while at Haskell. The headstones are promptly faced away from the buildings, and many people have left little items at the grave sites such as children’s toys, or rocks and crystals. On the campus, there is land where some of the children would run through, attempting to escape; however many of them didn’t make it. Visiting Haskell, a visit to the cemetery feels like you are there with the children sharing that grief and really taking time to think.

Marked graves at Haskell. (Photo/Karen Middleton)

Marked graves at Haskell. (Photo/Karen Middleton)

There is also an oral history of unmarked graves, on land that has been sold to the University of Kansas, according to Campbell.

Today, Haskell Indian Nations University is a four-year college operated by the Bureau of Indian Education.

Thinking about reconciling this dark past with the present day, Campbell says, “Through education, through saying, yes, that happened; Acknowledgement is the biggest part of that. I think, just to acknowledge that did happen here, that is, truthfully what we were established for. And how are we making that right? What we are doing now is we are educating and training people to Native people in particular, to come into the government and fill these positions so that this doesn't happen again. I think that's the biggest thing we can do is prevent anything like this from ever happening again.”

A grave at Haskell. (Photo/Karen Middleton)

A grave at Haskell. (Photo/Karen Middleton)

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher