- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

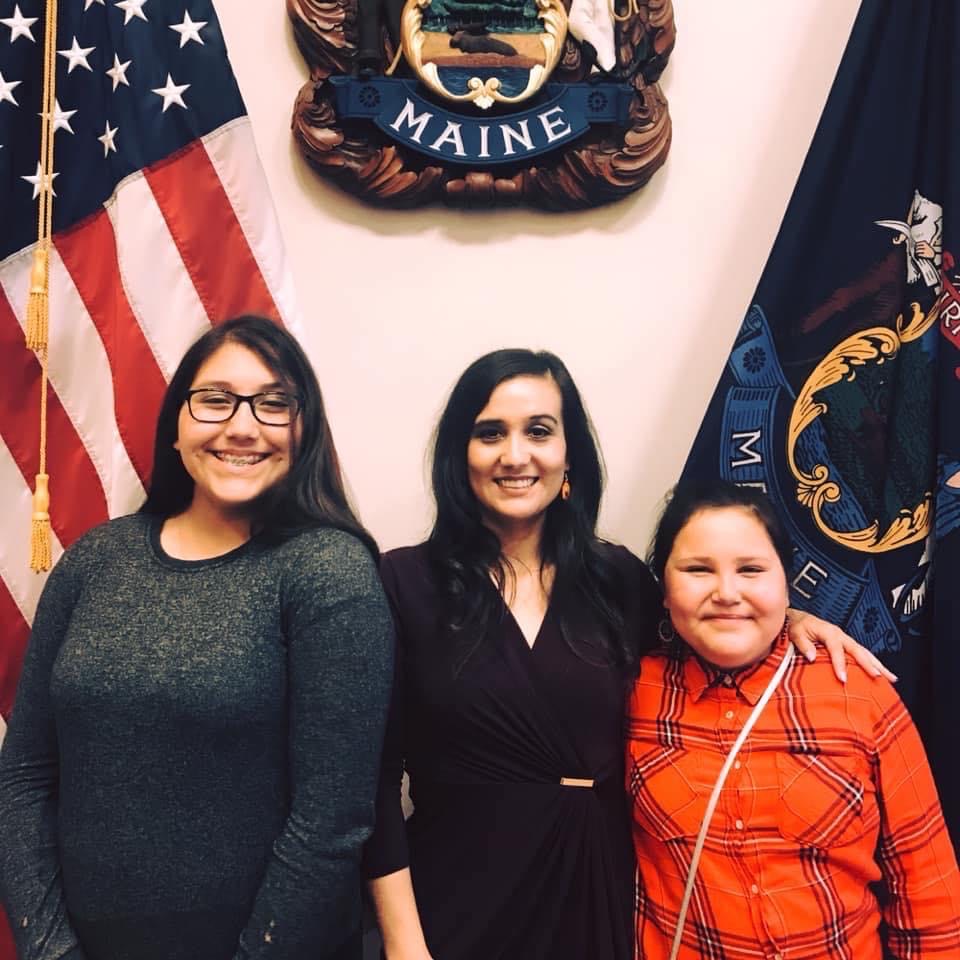

For Penobscot Nation ambassador Maulian Dana, the Violence Against Women Act reauthorization signed into law by President Joseph Biden March 16 is personal.

It’s the first time in history that Maine’s four federally recognized tribes—known collectively as the Wabanaki Nations—have been named in federal legislation passed for the benefit of tribes in the United States. That’s because the state’s unique jurisdictional arrangement with the tribes, derived from the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980, gives it certain powers over tribes that are normally reserved for the federal government.

That distinction limits tribes’ authority in setting their own tax structures, court jurisdictions, regulations on fishing and hunting on tribal land, land use and acquisition rights, and access to federal funding—which is ultimately the reason they’ve been historically left out of the protections of the Violence Against Women Act, which allocates resources to states and tribes to help prevent and improve response to domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Statistics show that one in three Indigenous women will be a victim of a violent crime in her life.

“I have two daughters—they’re 13 and 15—so that makes three Indigenous women in my family,” Dana told Native News Online. “I used to say, ‘I really hope that one woman is me,’ but I’m about eight months pregnant with my third daughter. Now, I still hope it's me, but [soon they’ll be] four of us.”

Dana and other Indigenous women in Maine can now lean on a federal law to help protect them against violence.

“Living in Maine, where the population is not all that diverse, there's a really good chance that, with domestic violence happening, the offender is non-Native,” Dana said. “So this is super, super-important to make sure we can address violence and dysfunction and trauma. But then we also need to make sure there's mechanisms in place for justice.”

The landmark Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) was first enacted in 1994, and reauthorized in 2000, 2005, and 2013. This year’s bill authorizes $7 million annually for fiscal years 2022 through 2026 to pay for tribal training, technical assistance, data collection, and evaluation of participating tribes’ criminal-justice systems of. It also appropriates $3 million annually through the same period for tribal governments to access and use federal criminal information databases.

For tribal nations, the most important aspect of the VAWA reauthorization is its restoration of tribal jurisdiction for certain crimes perpetrated by non-Natives.

In the United States, 96% of perpetrators of sexual violence against Native women are non-Native, according to the National Congress of American Indians.

Although the bill marked the first time Wabanaki tribes were listed specifically in the VAWA reauthorization, Dana said the Penobscot Nation and the Passamaquoddy Tribe fought hard in 2019 for Maine to pass a law that effectively extended VAWA protections to their tribes—the only two in the state with their own tribal courts.

“The tribal court—without VAWA jurisdiction–couldn’t bring these cases if the perpetrator was a non-Native person,” Dana said. “That led to no justice whatsoever in a lot of our domestic violence cases, [since] a lot of these cases were non-Native perpetrators.”

Now, all four tribes will have access to new federal funding, training opportunities, and decision-making in the implementation of VAWA. Corey Hinton, attorney for the Passamaquoddy Tribe (and an enrolled member), told Native News Online that it is “extraordinarily expensive” for tribes to implement the Violence Against Women Act.

“While it's extremely important, and it's extremely attractive, It's a very serious undertaking for tribal governments to build a court that can provide the types of protections that are necessary under VAWA,” Hinton said. “It's an intensive process that has a lot of deliberation along the way, but that's what nation-building is about, and that's what the Wabanaki Nations will have the opportunity to do under this new VAWA.”

Next up for tribal nations in Maine are three pieces of legislation heading to the state House in a couple weeks, then the Senate, then to Governor Janet Mills’ office.

The largest of the three bills, LD1626, is comprehensive legislation that would reinstate the four federally recognized tribes’ sovereignty. The second one deals with land acquisition rights and the ability for Maine tribes to build casinos: Despite two operating commercial casinos in the state since voters approved gaming in 2003, tribes have yet to gain state approval to build their own casinos. The last bill would empower the Passamaquoddy Tribe to regulate its drinking water—which comes from a polluted reservoir—as all other tribes in the U.S. are able to do.

Dana said the tribes are “cautiously optimistic” all three measures will pass, especially the sovereignty bill.

“The governor has expressed concerns about the overall issue of amending the Settlement Act,” Dana said. “So we're just working really hard to make sure we can address those issues, and hopefully advocate for the passage. We're hopeful that we're in a very good moment for tribal-state relations in Maine, no matter what happens.”

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsNavajo Nation President Nygren Files in Court to Halt Removal Legislation

Alcatraz Sunrise Gathering Marks 50 Years of Indigenous Activism

Navajo Nation Vice President Distances Herself From President After Removal Resolution

Navajo Council Speaker Introduces Legislation to Remove Navajo Nation President, Vice President Amid Ethics Complaint

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher