- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

Under legislation passed by Congress in 1990 — the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) — certain cultural artifacts, funerary objects, and human remains held by museums and federal agencies are subject to a process of federal review and return to their respective tribal nations.

But NAGPRA doesn’t apply to the 173 Native children buried on federal lands in Carlisle, Pa., according to the US Office of Army Cemeteries, which oversees the graveyard.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Instead, the Army has instituted its own process for returning the youth buried at Carlisle. That process, though, is too restrictive to tribes seeking justice and healing, according to attorneys who specialize in repatriation matters and the application of NAGPRA.

“It does apply,” Shannon O’Loughlin (Choctaw), chief executive and attorney of the Association of American Indian Affairs (AAIA), said of NAGPRA. “The Army Corps has just refused to follow NAGPRA and instead has created its own form and process. Federal law has precedent over agency policy.”

To understand the difference of opinion, Native News Online spoke to attorneys from: the Office of Army Cemeteries, the Association of American Indian Affairs, the Native American Rights Fund, and the Chestnut Law Offices, P.A., which represents primarily pueblo tribal governments. Native News Online also spoke with the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, which last month successfully brought home to South Dakota nine of their children who were buried at Carlisle for as long as 142 years.

Both the Department of the Interior—which is responsible for implementing NAGPRA—and the National Park Service that provides guidance for complying with the law and regulations declined to comment, instead deferring to the Army’s opinion.

194 children

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was established at the former U.S. army barracks by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1879, and served as the United States’ first off-reservation boarding school for Indigenous children. Over the next 39 years, some 7,800 Native children were forcibly removed from their homes across Indian Country and sent to the Carlisle Indian school as part of the U.S. government’s assimilationist agenda, according to archivist Jim Gerencser from the Carlisle Indian School Digital Research Center, run by nearby Dickinson College.

Until it closed in 1918, the school buried the bodies of at least 194 Indigenous children in the school cemetery, including 14 of whom are marked with “unknown” grave markers.

Many of the students’ deaths were announced in the local newspaper at the time, noting causes of death as “consummation,” or tuberculosis, or detailing circumstances of unknown sickness. In 1927, the U.S. Army moved the cemetery from its original location to a street next to the barracks entrance.

The Cumberland Valley Historical Society has worked to document the names and tribal affiliations of almost all of the interred individuals, including nine of the unknowns, but local historians and descendants say it's more than likely many living relatives are unaware of their ancestors buried at Carlisle.

A formalized process for return

Beginning in 2017, when Northern Arapaho woman Yufna Soldier Wolf successfully petitioned the Army to exhume three of the tribe’s children, the Office of Army Cemeteries formalized a process of returning Native youth to their lineal descendants. Since then, the Army has paid for four transfer ceremonies, returning a total of 21 children buried at the Carlisle school cemetery to burial grounds chosen by each descendant.

But the Army says that NAGPRA doesn’t apply to the Carlisle Main Post Cemetery “because the remains are not part of a collection,” they wrote in a Federal Register Notice of Intended Disinterment this year.

Instead, the Army would follow its own rule for exhuming Native American remains: Army Regulation 290-5, which requires a request for disinterment be made by a lineal descendant.

“Under army policy, and because we have the custody of the remains, we have to allow the family to be the one that notifies us,” Renea Yates, the director of the Office of Army Cemeteries, said. “Tribal requests cannot be made. It has to be the individual, closest family member.”

This is where other attorneys disagree.

‘More restrictive than what the law provides’

“What happens if there’s no linear living descendant?” asked AAIA’s O’Loughlin. “I think it's good of them to reach out to the tribes and say ‘these are the children affiliated.’ But then to require the families to have to come forward may be difficult for many, many reasons.”

Attorney and executive Shannon O’Loughlin argues that NAGPRA should supersede Army policy because the Carlisle Main Post Cemetery is on federal lands. (Photo/AAIA)O’Loughlin argues that since NAGPRA applies to federal agencies in addition to museums, and the Carlisle Main Post Cemetery is on federal lands, NAGPRA should supersede Army policy.

Attorney and executive Shannon O’Loughlin argues that NAGPRA should supersede Army policy because the Carlisle Main Post Cemetery is on federal lands. (Photo/AAIA)O’Loughlin argues that since NAGPRA applies to federal agencies in addition to museums, and the Carlisle Main Post Cemetery is on federal lands, NAGPRA should supersede Army policy.

Under NAGPRA, a tribe could claim their ancestor if no lineal descendant were known, thereby simplifying the process for Nations with known ancestors buried at Carlisle.

“The agency is following a policy that’s more restrictive than what the law provides,” she said. “Which is for affiliated tribes to be able to repatriate.”

The Army’s process for a lineal descendant to claim an ancestor buried at Carlisle requires two notarized affidavits: one from the closest living relative requesting the disinterment stating the reason for the proposed disinterment, and a second from a person who knows the closest living relative supporting their relationship to the deceased.

O’Loughlin said the policy written by the Army and doesn’t take into account the way tribal nations function.

“Our biggest concern is that this be as easy as possible, that it doesn't burden the relatives or or descendant tribes any further,” she said. “And the kind of forms and the affidavit and the information that … are required by Army Corps seems to be more burdensome than perhaps just getting a permit to disinter and releasing the ancestors to the affiliated tribe, and then let the tribe determine lineal descendancy however it wishes to.”

‘We didn’t want to pick a fight’

Lloyd Guy, general counsel for the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota, said that the tribe didn’t push NAGPRA with the Army because it didn’t want to risk not getting their relatives back at all.

“We didn’t want to pick a fight because we want our bodies back,” Guy said. Even after last month’s exhumation of nine of their children, Rosebud Sioux chairman Russell Eagle Bear said the tribe has eight more relatives buried at Carlisle they weren’t able to exhume last month.

Guy said that the tribe respectfully disagrees with the Army’s interpretation of NAGPRA, though it shouldn’t interfere with other tribal relatives’ rights to ask for their ancestors' remains.

“I would think this is what NAGPRA is talking about,” Guy said of the Carlisle Cemetery. “The Rosebud Sioux Tribe were (and) are focused on bringing back our relatives, so we moved forward.”

Native American Rights Fund attorney Matthew Campbell (Native Village of Gambell) agreed with O’Loughlin and Guys’ interpretation of NAGPRA. “I agree with both Lloyd and Shannon’s view that it appears NAGPRA does apply,” he wrote to Native News Online. So did Aaron Sims (Acoma Pueblo), an attorney specialized in cultural resource protection at Chestnut Law Offices in Albuquerque. “With my understanding of NAGPRA…. it is very arguable that it should apply. I think, to me, the federal land definition is fairly clear under NAGPRA.”

Jim Thorpe as precedent

According to the Office of Army Cemeteries attorney Justin Buller, a 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals case established precedent informing the army’s opinion on NAGPRA as it relates to a graveyard.

The 2010 case dealt with the applicability of NAGPRA on a municipality receiving federal funds, coincidentally near Carlisle.

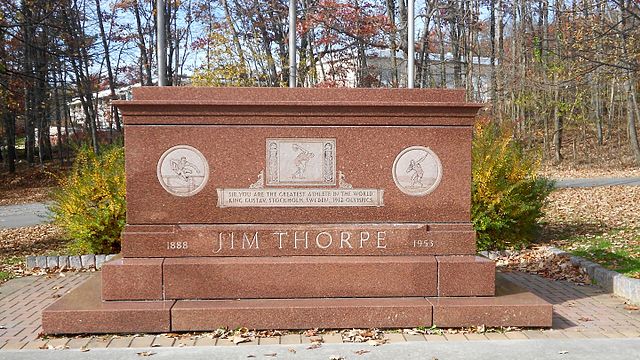

Legendary gold medalist and former Carlisle student Jim Thorpe died in California in 1953, and his third wife buried him in a municipality in Pennsylvania that is now named after the athlete.

Decades later, Thorpe’s son and second wife sued the municipality for failing to comply with NAGPRA by not returning Thorpe to his tribal lands of the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma.

A 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals case involving the remains of Jim Thorpe established precedent informing the Army’s opinion on NAGPRA, according to an attorney from the U.S. Army. (Photo: Wikipedia) A District Court originally concluded that the borough was a “museum” within the meaning of NAGPRA, and therefore required to disinter Thorpe's remains and turn them over to the Sac and Fox tribe. That decision was later overturned by the 3rd Circuit for its “clearly absurd result.”

A 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals case involving the remains of Jim Thorpe established precedent informing the Army’s opinion on NAGPRA, according to an attorney from the U.S. Army. (Photo: Wikipedia) A District Court originally concluded that the borough was a “museum” within the meaning of NAGPRA, and therefore required to disinter Thorpe's remains and turn them over to the Sac and Fox tribe. That decision was later overturned by the 3rd Circuit for its “clearly absurd result.”

“The court specifically ruled that this (NAGPRA) is to protect remains that are properly entered,” Buller said. “It is not a two-edged sword that, on one hand, protects graves, and on the other hand, it can be used to direct that they be dug up. That's exactly what we're talking about here.”

But NAGPRA has three main provisions to it: to repatriate; to protect graves; and to prevent illegal trafficking of human remains.

Under the gravesite protection provision, the law specifies protocol for “Intentional excavation and removal of Native American human remains and objects.”

O’Loughlin said the Thorpe case was labeled as a “family dispute” and therefore was looked at outside of the purpose of NAGPRA, but the 3rd Circuit’s decision does not apply to the graves protection provision of the law.

“The purpose of the excavation to return children that were kidnapped and forced to go to Carlisle as part of federal genocide and assimilationist policies is absolutely contemplated by the language of this human rights law to return the ancestors that were stolen,” she said.

A major difference between the Thorpe case and the Carlisle Cemetery is that Thorpe was buried by his wife, whereas the 173 children interred at Carlisle were intentionally not returned to their families. In at least two instances, childrens’ parents—after learning of the death of their children—wrote to the school requesting the return of their remains in 1880. Those children, Ernest Ernest Knocks Off (White Thunder) and Maud Little Girl (Swift Bear), were finally brought home last month.

Policy overhaul

The Department of the Interior announced on July 15 that it will begin consultations with tribal and Native Hawaiian community leaders about an update of NAGPRA regulations. The first session is scheduled for Monday, Aug. 9 at 3 p.m. EST, with subsequent consultations on August 13 and 16.

The draft proposal, based on tribal requests dating back to 2010, effectively seeks to simplify the repatriation process, putting the onus on museums and federal agencies to initiate the process rather than tribes.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) called the overhaul “long overdue.” Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Bryan Newland (Bay Mills, Ojibwe) specifically referenced the need for a better process as the nation works to confront the history of Indian Boarding Schools.

“As the Department continues its work to confront the history of federal boarding schools – including returning the human remains of Native children to their families – we will implement the policies and requirements of NAGPRA to address Tribal concerns,” Newland said.

‘Ready, willing, and able’

Despite rejecting NAGPRA applicability, Buller said the Army is willing to work with descendants wanting to bring their relatives home.

“The Army stands, ready, willing and able, for any family that makes the request and completes that relatively straightforward paperwork necessary,” he said. “Our promise to them is that we will go forward with disinterring at our expense and returning to them at our expense, that our loved one, and you were ready to do that for any of the children that we know to be buried in that cemetery.

At the Rosebud Sioux tribe’s dignified transfer ceremony on July 14, tribal councilman Russell Eagle Bear told the crowd in attendance “right now, we’re stuck on military process,” but vowed to help other tribes repatriate the remains of their children from Carlisle.

“We’re going to make sure that each tribe is contacted, and each child brought home,” Eagle Bear said.

O’Loughlin said she hopes continued exhumations at Carlisle help spur change in legislative policy, but only if the tribes feel undue burden from the Army’s process.

“If the tribes and the descendants are willing to follow their process, then I'm not going to argue with it,” she said. “But if it’s causing more burden and more harm, then I think it's problematic.”

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story has been updated to properly reflect the number of transfer ceremonies paid for by the Army.

More Stories Like This

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal SovereigntyNavajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Northern Cheyenne Push Back Against Trump Administration’s Effort to Alter Little Bighorn History

Florida Man Sentenced for Falsely Selling Imported Jewelry as Pueblo Indian–Made

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher