- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

The 140-page report, researched and prepared over the last year by state archeologist Holly Norton, was commissioned by Colorado lawmakers in a May 2022 House Bill. The legislation recognized that in Colorado, a state that hosted at least nine federal Indian assimilation schools, “...the boarding school policy resulted in long-standing intergenerational trauma.”

In order to heal from that intergenerational trauma, representatives wrote, “we must confront the past and shed light on hidden cruelty.”

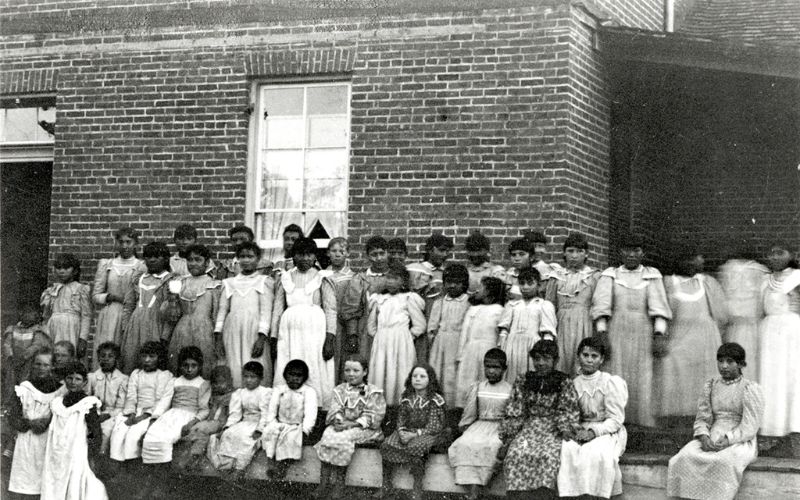

Lawmakers directed the state historical society, in consultation with tribal nations, to research the events, physical and emotional abuse, and deaths that occurred at Colorado’s Indian boarding schools, particularly at the two off-reservation boarding schools: The Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School, which now operates as Fort Lewis College in Hesperus, Colorado, and Grand Junction Indian Boarding School, or Teller Indian School. Both institutions operated as off-reservation Indian boarding schools until 1911.

State researchers also conducted non-ground-disturbing research at Fort Lewis Indian School to identify potential cemeteries and unmarked graves of children who once attended the school. The results showed that the Fort Lewis’ cemetery “is the final resting place of 350 to 400 individuals,” the report notes. “Of these, 46 are hypothesized to be children, with the remainder either adults or adult-sized juveniles.”

An archival analysis of federal, state and local records found at least 31 students’ deaths over 18 years at Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School. “The number of deaths is a nearly threefold increase over what appear to have been the deaths officially reported to Washington, DC, in annual reports,” Norton wrote in the report.

The archaeologist told Native News Online that the number of deaths at Fort Lewis was extrapolated from multiple sources.

"We looked at correspondence between Superintendents and others including officials at the Indian Affairs Commission, individual Indian Agents, and other Superintendents or officials; newspaper obituaries; and sometimes we would find specific mentions in what seemed like random documents,” Norton wrote to Native News Online. “It seems odd because the numbers weren’t being hidden per se, but the Superintendents were not carefully aggregating the data on student deaths for their annual reports. That is why there is a discrepancy in the numbers.”

Researchers also determined that at least 33 Native students died at Grand Junction Indian Boarding School, plus a teacher, a carpenter’s daughter, and two former students.

Leaders of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and the Southern Ute Indian Tribe—the only remaining federally recognized tribes in Colorado who sent their children to both schools—called the report unsurprising and just the beginning.

“It’s just the tip of the iceberg,” Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Chairman Manuel Heart told Native News Online. He said he expects the total number of student deaths to be higher with continued investigation. “There is more to be said [and uncovered] down the road. It’s a healing process, for not only Ute tribes in Colorado but other tribes who were also involved [in the federal Indian boarding school era].

Chairman Melvin Baker of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe said in a statement to Native News Online that, while disheartening, the results of this report “come as no surprise.”

“The lived experiences and firsthand accounts of our parents, grandparents, and elders have long echoed the painful realities of this era,” he wrote. “This was during a time when education was weaponized to eradicate Ute culture, language, and identity. This report serves as a step towards confronting and comprehending the enduring impact of the Federal Indian Boarding Schools on the Southern Ute people.”

Chairman Heart encouraged other states to follow Colorado’s lead and conduct their own research, on top of the Federal Indian Boarding School Investigation.

In May 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) released Volume 1 of its Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, a 106-page report detailing the history and ongoing legacy of the federal government’s 150-year policy of forcibly assimilating Native American children into white culture by sending them to Indian boarding schools.

The report found that the federal government operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states between 1819 and 1969. A second report, with an aim to identify unmarked graves, student burial sites, and the names and tribal affiliations of children interred at each location, is due out this year, according to the Interior.

The Interior Department declined to comment on the Colorado report.

“States also need to be involved in [investigation],” Chairman Heart said. “In order to really, truly heal from this with tribes, states need to be involved.”

Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition Chief Executive Officer Deborah Parker (Tulalip) called the Colorado report painful yet necessary, and echoed Chairman Heart’s call to mobilize other state governments to conduct their own research with tribal nations.

“We encourage other states to follow suit,” Parker told Native News Online. “To take measures to better comprehend the atrocities that Indigenous peoples faced while attending these institutions, and to recognize the role of state governments provoking multigenerational harm to Tribal Nations.”

More Stories Like This

Committee Advances 20% Increase to Navajo Child Support GuidelinesNavajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement Plan

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher