- Details

- By Levi Rickert

OPINION. My mother taught her children the power of reading and learning. When I was in elementary school, she took me and my siblings to the local library on Saturday mornings. My lifelong love of biographies began when I selected books to check out of the library to read. I read the biographies of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt and other American historical figures.

They became heroes to me.

Those perceptions changed dramatically one day during my eighth-grade American history class. The assignment was to read the Declaration of Independence in our red, white and blue history textbook while sitting in class. As I read Thomas Jefferson’s words in the Declaration of Independence, I had a sudden awakening of how American Indians were viewed historically. The same man who wrote the words, “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal” continued, in the fourth paragraph from the end with “…the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare…”

That was a defining moment of enlightenment that changed the way I have viewed American history ever since. Those words written by Jefferson that depicted Indians so unfavorably angered and hurt me, because the “Indian savage” he wrote about was not anything like the American Indians I knew in my family or Indian community. They were far from being “savages.”

As an American Indian, I now realize that American history is complex and often messy.

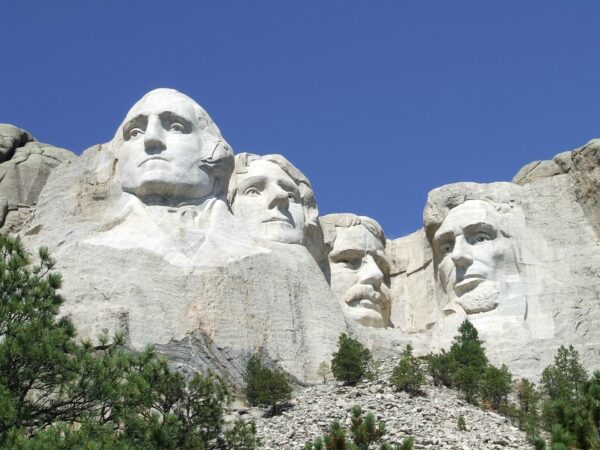

The trip to South Dakota to visit Mount Rushmore by President Donald Trump scheduled for this Friday as a pre-Fourth of July celebration reminded me of the dichotomy between the American patriotic view, and the viewpoint that many American Indians have of the tourist attraction that draws almost three million visitors each year.

For Trump, the mountain represents a great photo opportunity during a presidential election year. Mountains make great backdrops for photographs of course, but I suppose a mountain with four U.S. presidents’ faces provides an even more majestic view.

The president’s visit to the mountain will be met with protests from American Indians. But they will not be there as an extension of the Black Lives Matter protests that have sprung up across the country after George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police last month. In fact, American Indians have been protesting Mt. Rushmore for decades.

They will be there because they know the other side of the mountain story that is seldom taught to American students, who only hear the patriotic version of how great the four presidents were in American history— so great that it warranted their likenesses to be carved into the side of the mountain.

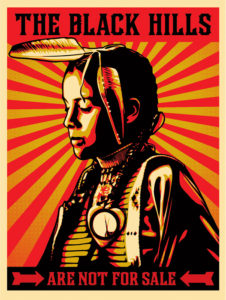

What the American Indians know, particularly those from the great Sioux nations, is that the tribes were originally given the Black Hills, which Mount Rushmore is a part of, in perpetuity in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Soon thereafter, gold was discovered in the Black Hills and greed set in. The U.S. Calvary moved in by the mid-1870s to protect white miners. The U.S. government took the stance that American Indians had the choice to “sell or starve.” By 1877, the Sioux nations’ land was confiscated by the federal government and the Sioux were forced onto reservations.

What the American Indians know, particularly those from the great Sioux nations, is that the tribes were originally given the Black Hills, which Mount Rushmore is a part of, in perpetuity in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Soon thereafter, gold was discovered in the Black Hills and greed set in. The U.S. Calvary moved in by the mid-1870s to protect white miners. The U.S. government took the stance that American Indians had the choice to “sell or starve.” By 1877, the Sioux nations’ land was confiscated by the federal government and the Sioux were forced onto reservations.

The Sioux nations have maintained they are the rightful owners of the Black Hills. They took the federal government to court and in 1980 the U.S. Supreme Court agreed the land was taken from them wrongfully. As a result, a trust account was set up with $102 million for compensation.

The Sioux said they did not want the money, they want the Black Hills back. The fund is reportedly now worth more than $1 billion.

Last week, Oglala Sioux Tribal President Julian Bear Runner said that he wants the faces of the four presidents removed from Mount Rushmore. But he indicated this should not be done by blowing up the side of the mountain, because it would bring more desecration to the mountain that the Sioux still consider sacred.

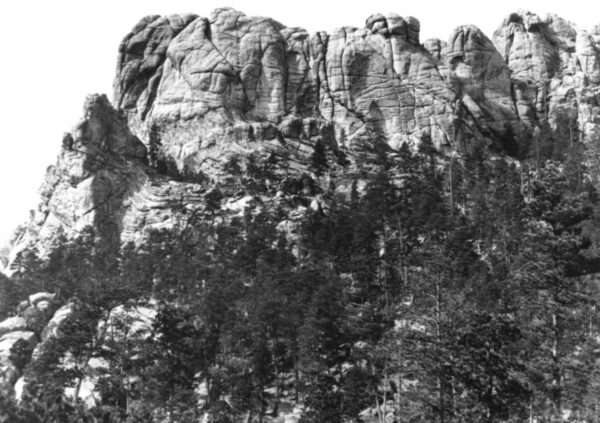

Mount Rushmore before work began. Photo from National Park Service archives.

Historian James W. Loewen, author of Lies My Teacher Told Me, said in an interview with the Washington Post in February 2000, “The other part of the Rushmore story that needs to be told is about its sculptor, Gutzon Borglum. He was a leader of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, and his association with the Klan shows how mainstream the group was. President Harding was actually sworn into the Klan at a White House ceremony. In fact, Mount Rushmore has been considered a Ku Klux Klan sacred site.”

As I said, American history is messy and much more complicated than most people even know.

On Sunday, South Dakota state Senator Troy Heinert (Rosebud Sioux), who is current minority state senate leader, told me he is concerned about further spread of COVID-19 with all the Trump supporters, who are not prone to social distancing, in a state that in recent days has seen spikes in new COVID-19 cases. He is also concerned about potential for fires breaking out in the land around Mount Rushmore since it has experienced drought conditions that have prohibited fireworks there since 2009.

He further said he knows the history of ownership of the Black Hills. He hopes the presidential visit will shed light on the other side of the mountain story that Americans should learn.

I agree. Trump’s visit should be an opportunity for Americans to finally learn the truth about stolen land and the desecration of a mountain that depicts the faces of four presidents who are not necessarily heroes to American Indians.

I learned the truth when I was in eighth grade - that there is a real difference between the “history” that is taught in school, and what American Indians know to be true.

More Stories Like This

The SAVE America Act Threatens Native Voting Rights — We Must Fight BackThe Presidential Election of 1789

Cherokee Nation: Telling the Full Story During Black History Month

Jesse Jackson Changed Politics for the Better

Native News Online at 15: Humble Beginnings, Unwavering Mission

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher