- Details

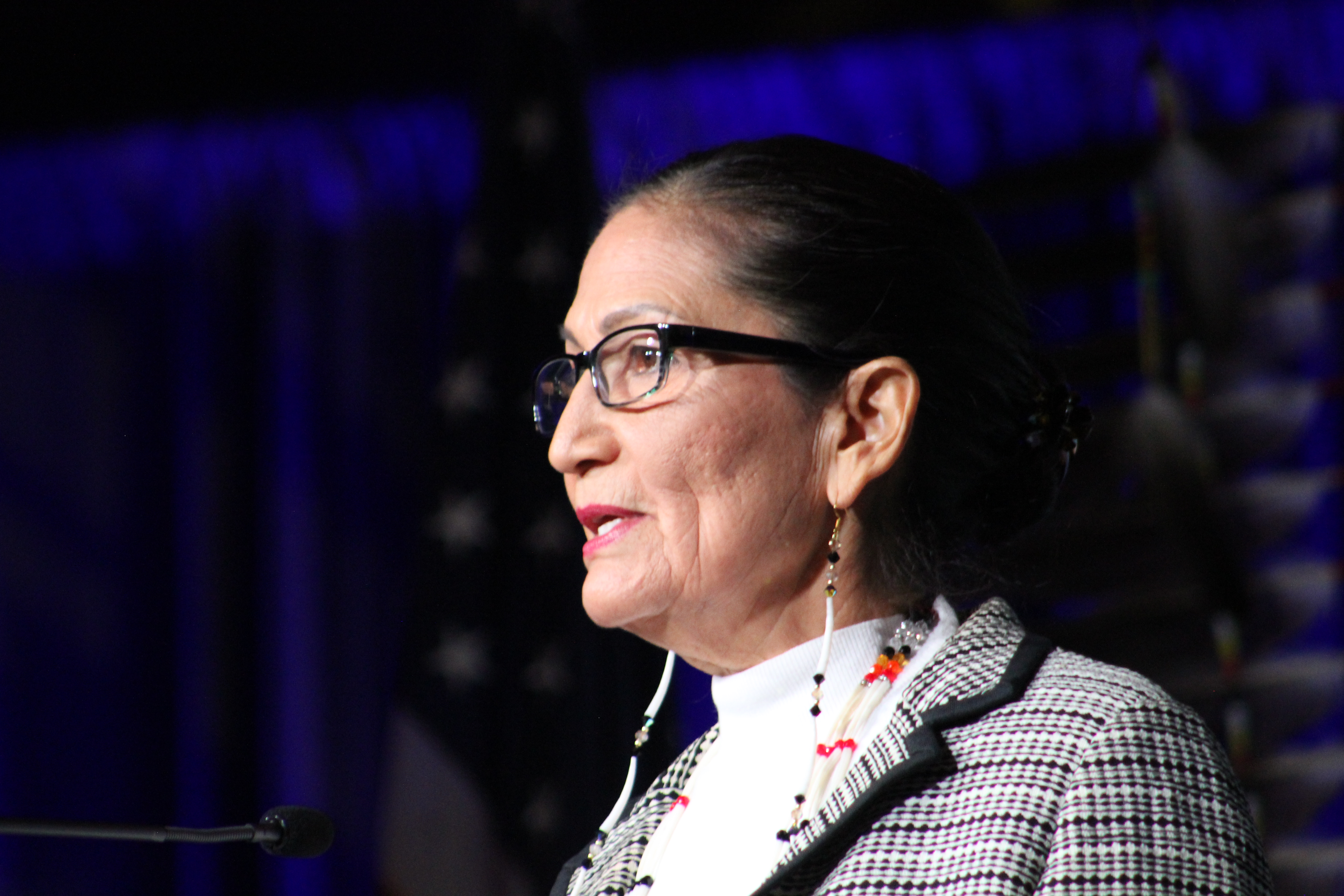

- By Deb Haaland

Guest Essay. I am a proud American citizen, committed to doing my part and to asking what it is I can do for my country. Yet it is difficult to view my present without considering my past – my entire past. So much happened leading up to the signing of the Indian Citizenship Act – the law which granted Native Americans in the United States citizenship – one hundred years ago this year. I am here because of the dedication of the ancestors and their instilling within me a sense of obligation to our community and our country.

On the snowy morning of December 2, 1960, I was born into the arms of my mother in Winslow, Arizona. My grandparents had lived there and worked on the railroad since the early 1920s, making the most out of the federal government’s Indian assimilation policies they had sacrificed so much to be a part of. Helen and Tony met at St. Catherine’s Boarding School in Santa Fe, where the government and the Catholic Church had agreed to send many of the Pueblo Indian children who were part of this era of family separation.

[In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, Native News Online will publish during the month of June guest essays to provide our readers with various perspectives from prominent Native Americans on the subject. Today's was written by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland.]

My grandfather’s eventual career as a diesel train mechanic, and his presence at the Winslow Indian Camp where rail workers and their families lived in old boxcars and built community, helped instill pride in our people. He galvanized his peers around pastimes like coaching an all-Indian baseball team, which he led to the state championship, and playing brass horn in the Santa Fe Indian Band, which marched in President Eisenhower’s Inaugural Parade in January of 1953. In Winslow, the people worked hard to preserve our culture and our traditions so far away from our homelands. I know what it means to be a Pueblo woman because of their profound efforts.

To me, the people of Laguna have always thought of themselves as United States citizens. They worked hard, respected the land, and strove to be role models for younger generations. But I am ever mindful that they did so for many decades without having their legal status recognized by our country — and even after the Indian Citizenship Act was enacted, without receiving access to full benefits such as the right to vote from the state of New Mexico.

It’s worth remembering that when Louis Tewanima and Jim Thorpe – two history-defining Native athletes – traveled to Stockholm to compete in the 1912 Summer Olympics on behalf of the United States, they did so not as American citizens. They won Olympic medals in the name of our country, and they did so with a sense of pride. From the Village of Shungopavi in Second Mesa, Arizona, Louis Tewanima would run the 50-plus miles to Winslow just to watch the trains. When the caboose passed by, he would turn back home. His connection to the earth still gives runners – even slow ones like me – the contemplation and respect necessary to appreciate the physical abilities that Creator has bestowed upon us.

Similarly, Miguel Trujillo – an Isleta Pueblo member and U.S. Marine in World War II – returned to New Mexico after putting his life on the line for our country and for democracy. All that sacrifice, yet he couldn’t vote in state elections. He sued the state of New Mexico and won. He won for me and for every other Indigenous person in the state, and that is a debt I personally owe. I know there are many other stories of Native leaders and organizers in states across the U.S. who also fought to ensure this foundational right.

Of course, following Mr. Trujillo’s court victory in 1948, Native Americans in New Mexico could finally vote, but that didn’t remove every obstacle we faced at the ballot box. And truly, the fight for free and fair elections for Native Americans—and for women and other people of color across our country—continues to this day. When I was much younger and during every election cycle, I took it upon myself to get my fellow Indians to the polls. It is more important than ever that Indigenous folks recognize our obligations as American citizens. There is simply too much at stake to sit out.

Even before the struggle for citizenship, our Native heroes have consistently risen to seemingly insurmountable challenges. They are those who rose up to protect the few remaining bison after the great slaughter and near-total destruction of the Great Plains; who fought for hunting and fishing rights on our ancestral homelands; and who served our country in times of peace and in times of turmoil. We must honor their legacies.

Through the years, I have been asked many times why I believe the number of Veterans in Indian Country is so large. I have always surmised that this is our land, so who better to fight for it than us? As I have visited with Tribes across the country, I hear over and over again: military service is a proud part of every Native Veteran’s biography. One Memorial Day decades ago, while visiting my home of Mesita Village, my grandmother asked me to hang an American Flag from her front porch. She stated that she wanted people to know that our family members were among those who served.

It is difficult for me to order out the fireworks in celebration of the Indian Citizenship Act’s centennial, because my people were here long before the Mayflower and the Pilgrims, and before the cow was introduced to North America. We have always been citizens of this continent. Our citizenship runs deep, and in spite of every Indian war, assimilation policy, and outright assault on our land, animals, and ways of life by newcomers, we have persevered. Knowing that my ancestors survived to give me breath, and that my family’s customs and traditions have survived through it all, gives me hope that our future generations will also have them to pass down.

Deb Haaland (Pueblo of Laguna) currently serves as the 54th United States Secretary of the Interior. She previously served as the U.S. representative for New Mexico's 1st congressional district from 2019 to 2021 and as chair of the New Mexico Democratic Party from 2015 to 2017.

More Stories Like This

The SAVE America Act Threatens Native Voting Rights — We Must Fight BackThe Presidential Election of 1789

Cherokee Nation: Telling the Full Story During Black History Month

Jesse Jackson Changed Politics for the Better

Native News Online at 15: Humble Beginnings, Unwavering Mission

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher