- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

PHOENIX, Ariz. — In the first weekend of March, hundreds gathered at Phoenix’s Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market, greeting friends and fellow artists with embraces, kisses and handshakes. There was a bit of Covid-19 buzz among the crowd, but people weren’t paying it much mind yet.

“It was still normal. Nobody was walking around with masks on. Everybody was hugging,” said beader LeJeune Chavez (Santo Domingo, Kewa Pueblo). “When we got home our governor made a public announcement she was shutting everything down. That's when it really hit us.”

Choctaw artist Karen Clarkson was having a ball at the Heard, visiting with old friends she sees year after year, and connecting in person for the first time with folks she’d only known from a distance.

One of the friends Clarkson hadn’t previously met in person was Navajo weaver Naiomi Glasses, the star of one of Clarkson’s “Year of the Woman” portraits. Glasses’s presence was especially poignant because Clarkson’s portrait of her ended up winning an award.

“Naiomi approached me with her mother and her brother Ty, took the photo of Naiomi that I used for the painting of her. They are all beautiful, strong Dinè and each of them extremely talented,” Clarkson recalled. “Neither Naiomi nor I knew that I had received a ribbon for the painting. She walked into the art preview show and saw her portrait hanging there for the first time. She was so surprised!”

A pair of Vera Wang heels with beadwork by Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market artist Marvin Gabaldon of Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo. (Marvin Gabaldon)Meanwhile, Penobscot weaver Theresa Secord was attempting to exercise caution.

A pair of Vera Wang heels with beadwork by Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market artist Marvin Gabaldon of Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo. (Marvin Gabaldon)Meanwhile, Penobscot weaver Theresa Secord was attempting to exercise caution.

“Some people weren’t even really aware of Covid-19 yet. I saw a bunch of collector friends, and they were trying to visit and hug. I was trying to do the elbow to elbow thing,” she said. “Things were starting to happen and there was the spread of this virus and there were advisories and the travel ban was just beginning.”

The Heard, which is the first must-go show of the market season, will go down in art history as the last Native art market of 2020 to take place at its intended physical location before a rash of pandemic-prompted cancellations and reboots: no hugging allowed.

In early April, major markets like the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Indian Market and Festival at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis and the Cherokee Art Market in Tulsa, Okla. began announcing cancellations, with some, including Santa Fe Indian Market and the Indian American Indian Arts Marketplace at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, boomeranging back weeks later to declare their markets would be held completely online.

Meanwhile, artists were left in the lurch, wondering how they would step up and survive with their major annual sources of income coming to a halt. Festival organizers had decisions to make, and quickly. With the whole state of the Native American art economy at stake, artists and market organizers alike were about to be hurled into an unprecedented virtual art world that would change everything — from the way artists and customers connect, to how competitions are handled.

The Santa Fe Experiment

Six months after the Heard, the grandest experiment in virtual markets, the Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market, is in the books. It ran through the whole month of August, and with more than 450 participating artists, it is the largest virtual market of the season.

“What we pulled off can take organizers years to implement. I have no criticism of it. None,” said Kim Peone, Director of the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA), which runs the Santa Fe Indian Market. “I feel really good about it. It’s definitely been new territory and there’s always going to be this adaptation that needs to occur. But it went surprisingly well.”

As for the numbers, Peone said the market created roughly $460,000 in sales, an average of about $350 per sale. SWAIA also increased membership by 144 percent, and just announced that the annual Winter Market will take place virtually for two weeks starting on Friday, Nov. 27.

The strategy behind transferring the Santa Fe Indian Market into an online event began taking shape in early April when the Market’s postponement was announced.

“At that time there was definitely a vetting process about going virtual, and within a two-week period we quickly pivoted and began to start that journey regarding a virtual Indian Market,” Peone said.

If the pandemic hadn’t forced the market online, this would have been considered the 99th Annual Santa Fe Indian Market. Organizers of the market, which started in 1922, have decided that this year’s online event won’t fully count towards its long history.

“It’s actually the 98th and a half because we had made the decision to make next year our 99th year and the centennial will be in 2022,” said Peone (Colville Confederated Tribes, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.)

This sweetgrass box by Penobscot weaver Theresa Secord won first place in the basketry category at the Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market. (Theresa Secord)

This sweetgrass box by Penobscot weaver Theresa Secord won first place in the basketry category at the Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market. (Theresa Secord)

The organizers’ primary concern was ensuring artists had the online capabilities and platforms they needed to participate because sales would depend entirely on the quality and ease of their online presence.

Peone said only 77 Indian Market artists already had an e-commerce presence prior to this year’s market. To equip all participating artists with websites, SWAIA partnered with Artspan.com, a web company providing e-commerce sites and attentive user support. As part of the market’s $200 entry and booth fee, SWAIA provided all participating artists a free, easily buildable Artspan e-commerce site that lasts for a year. When the website expires, the artist can renew for a small fee.

“On the market’s first day, the Artspan server actually crashed because of the amount of traffic they had from SWAIA, so that was exciting for them and us,” Peone said.

The market’s debut “was like a birth,” Peone said. “We literally gave birth to something and that was emotional. We definitely had weeping occurring.”

All the e-commerce sites are accessible through a landing page on the SWAIA website, and customers shopped those sites and contacted the artists through them with any inquiries. The landing page is still active and all the artist’s Artspan sites remain open for business.

To inject some face-to-face time for artists and customers, SWAIA also hosted a weekend of “Virtual Booth Hopping” via Zoom and provided business training to participating artists.

The art shopping and booth hopping was complemented by a daily menu of enriching online events and features, including in-depth “Coffee With Kim” interviews with some of the festival’s artists.

“Those are fun. You get to see a very real Kim Peone,” Peone said. “Those really came out of the idea that artists want to have that contact with the leader of the organization. It also gave them an opportunity to teach me. Just having a conversation and getting to talk about yourself and getting to talk to them, that to me, is very grassroots.“

Coffee with Kim and LeJeune & Joe Chavez from Santa Fe Indian Market on Vimeo.

Peone can’t predict what next year will bring in terms of mass gatherings, but SWAIA is ready to make the most of it either way.

“Even if we’re still in a place of restrictions, we’re prepared. When we produced and created the infrastructure for this virtual market, it was from the perspective of something we could use perpetually,” Peone said. “Even if we have Indian Market in person next year, we want to use our platform to promote that event. We have the tools to market artists all year now.”

Virtual veteran

Virtual market pro and Maine-based basketmaker Theresa Secord won first prize in the basketry category at the Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market.

“I’m getting to be good at this,” said Secord, who has participated in the Indian Market for 14 years. “I did the Digital Abbe Museum Indian Market in May and then the Digital Native American Festival and Basketmakers Market in July, so Indian Market was my third virtual market of the year. From each show I’ve gotten a couple orders, sales and new collectors.”

At the thoroughly modern Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market, Secord scored with a traditional piece: a replica of a sweetgrass and ash glove box basket her great grandmother made 100 years ago.

“It was cool to win with a really historic piece,” Secord said. “Even though there were fewer entries than usual, there were still some serious competitors I expected to get the prize over me.”

Secord said the whole process of competing was extremely altered, just like every other feature of the virtual market. She said judges selected five entries from each classification based on photos of the item, and the five finalists then had to mail the chosen pieces to Santa Fe. SWAIA reimbursed contestants up to $50 to mail their pieces.

A detachable choker and necklace set by Kewa Pueblo (Santo Domingo) bead artist LeJeune Chavez. (LeJeune)Organizers were still navigating the nuts and bolts of competition and writing the rules of the virtual market game while potential entrants were awaiting instructions. The real-time revamping and the experimental nature of the whole process resulted in some confusion and stress.

A detachable choker and necklace set by Kewa Pueblo (Santo Domingo) bead artist LeJeune Chavez. (LeJeune)Organizers were still navigating the nuts and bolts of competition and writing the rules of the virtual market game while potential entrants were awaiting instructions. The real-time revamping and the experimental nature of the whole process resulted in some confusion and stress.

“I was tempted not to send the basket at all,” Secord said. “We had a very short time window in uploading samples of work.”

In a regular year, “some of us are still working the night before the entry deadline, so there was none of that this year,” Secord said. “The deadline was a couple weeks in advance of usual for entering the juried competition and some people weren’t ready. It was hard to be motivated for a deadline. When you’re physically packing up baskets and flying to New Mexico, you’re on task and you’re making sure you have inventory.”

Overall, Secord was pleased with how SWAIA handled this year’s market.

“It was good. As good as can be expected given the times and the challenges,” Secord said. “You really had to be savvy, virtually speaking, and it was a challenge for me to step up and learn all the ropes of how to present art online.”

This year’s lack of live markets has significantly affected Secord’s income.

“For me, profits have been at least cut in half,” said Secord, who prior to the pandemic was planning to take part in more markets, including Tulsa’s Cherokee Art Market, which was abruptly canceled this year and did not pivot online.

Secord said she is supplementing her income with artist assistance grants, and altering her approach to art making and marketing to survive in the virtual art world.

“It’s forced me to think about things in different ways and even adapt my making,” Secord said. “I’m weaving smaller, more commonplace, less expensive baskets and trying to get them out on Facebook. Basketmakers have always had to adapt.”

Pivotal pioneer

On May 16, the Digital Abbe Museum Indian Market, the first Covid-era experiment in virtual Native art markets, launched from the far northeastern tip of the country.

The New York Times called Bar Harbor, Maine’s Abbe Museum the “unwitting virtual pioneer” of pivoting from a physical to a digital market because of the pandemic.

The Abbe celebrates the art and culture of the region’s Wabanaki people. Christopher Newell, the Abbe’s Executive Director and Senior Partner to Wabanaki Nations, emceed the six-hour event.

“I was broadcasting as host from the Abbe Museum itself and we used Zoom webinar for the artists to broadcast from their home,” said Newell (Passamaquoddy). “The artists gave 10-minute presentations either pre-recorded or live.”

The show was also broadcast on the Abbe’s Facebook and YouTube pages.

“We tried to make it as accessible as possible, and it turned out to be rather popular. The great part is it exposed the artists to audiences they normally wouldn’t be exposed to,” Newell said. “We had a pretty wide swath of viewers who wouldn’t have made it physically to the museum in the first place. Hopefully those are the people that are going to contact the artists.”

Like Peone, one of Newell’s main motivations behind the virtual market was driving viewers to a directory of artist profiles and e-commerce sites presented on the Abbe website’s Artists Database.

Newell and his Abbe colleagues gave the artists, most of whom were new to online marketing, tips, tricks and guidelines for successful presentations, from how to set up their in-home booths, to how  Choctaw artist Karen Clarkson sold the painting "Reverence" during August's Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market. (Karen Clarkson)to highlight a particular item on screen. There were also numerous tech checks.

Choctaw artist Karen Clarkson sold the painting "Reverence" during August's Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market. (Karen Clarkson)to highlight a particular item on screen. There were also numerous tech checks.

“We really planned and overplanned the hell out of it because we knew it was a live event and anything could happen,” Newell said

There were a few minor issues, like audio problems, but no major disasters.

Newell said he was fairly confident an online art market would work well for the artists because he had witnessed how Social Distance Powwow, a Facebook group with more than 200,000 members that popped up at the beginning of the pandemic, quickly became a major and highly profitable platform for Native artists to display and sell their work.

“Social Distance Powwow proved there was an audience,” Newell said. “That's where I got the idea for the Digital Abbe Museum Indian Market.”

As a result of Digital AMIM’s success, Newell said several museums and festival organizations, including the Autry Museum of the American West and the Eiteljorg asked to consult with the Abbe about pivoting to an online space.

In July, Newell and the Abbe added another virtual art market to their repertoire by working with the Maine Indian Basketmakers Association to present the first Digital Native American Festival and Basketmakers’ Market.

For two hours on July 11, Digital NAF was broadcast on the same three platforms as Digital AMIM. It followed the same plan as its predecessor, with artists broadcasting from their homes, where they set up display booths. About a half dozen basketmakers participated in live Q&A sessions with virtual visitors.

“It was much smoother. We learned quite a bit the first time around. It was a very educational experience and it ended up getting quite a high number of views,” Newell said. Virtual art markets, he added, “are the new world, and artists got to kind of cut their teeth on our two events.”

Success stories

From Santo Domingo Pueblo to Switzerland, and from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo to Japan, artists stepping up their virtual game are opening themselves up to a global marketplace and expanding their clientele.

Santa Fe Indian Market artist Marvin Gabaldon of Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo attracted a fan from the Land of the Rising Sun through his presence on the SWAIA website.

“I had one huge customer in Japan. That was pretty nice. She bought some peyote stitched earrings,” said Gabaldon, who specializes in beading. “She went online and looked at a bunch of different artists, and she had fun.”

A strawberry basket by Penobscot weaver Ganessa Frey. (Ganessa Frey)

A strawberry basket by Penobscot weaver Ganessa Frey. (Ganessa Frey)

Over at Kewa Pueblo (Santo Domingo), artist spouses LeJeune and Joe Chavez are corresponding with clients from across the pond.

“I did get an email from a man in Switzerland who’s very interested in our jewelry. I told him I’d let him know the rates and regulations and requirements to send to Switzerland. It sounds like he wants several pieces,” Chavez said. “I met a lot of people and we do have a new list of clientele through our website. It's all working out.”

Business is generally going well for the Chavezes, but they still miss live shows like the Annual Kewa Pueblo Arts and Crafts Market that usually happens on Labor Day weekend. Chavez said it’s a market she, her husband and her Pueblo neighbors count on each year to enhance their incomes.

“We’re not having it virtually either this year. For us, it’s a mile from our house. It’s just right here,” Chavez said. “That one is good too because a lot of New Mexico residents and people from surrounding states prefer it to Indian Market because they can actually get in the booths.”

For a few Indian Market participants, this virtual year paid off in a big way. Karen Clarkson sold three pieces, and they were all large, expensive paintings.

“I made more than I have in other years,” said Clarkson, who lives in Arizona. “The big advantage and what made it lucrative for me is that I didn’t have to pay for a hotel and the travel, and I didn’t have to rent a huge truck to haul my stuff around in. My expenses were only the $200 entry fee, so I came out way ahead of what I normally do.”

Intricacy and interactions

Through photos and videos it’s often tough to translate the intricacy of a sweetgrass basket, the weight of a stone pendant or the texture of a handwoven rug.

The inability of customers to see and touch pieces in person is one of the major downsides of virtual markets.

It’s an especially big issue in the case of wearable items. The disadvantage was evident to first-time Indian Market vendors Aunalee Boyd-Good and Sophia Seward-Good of British Columbia-based Ay Lelum Designs. Ay Lelum is a Coast Salish design house, in which all members of the Good family (Snuneymuxw First Nation) play a role.

“We would have sold a lot more had it been live, because with textiles people want to see and touch. And we’re new to people, too. At home, we have regular customers who know the quality that we make,” Aunalee said. “Had we already gone one year, and people had met us and seen the products, they would have been more apt to buy something.”

Indian Market was nowhere near a total bust for Ay Lelum. The sisters said they had a significant increase of U.S. customers and sales on their website.

“It was really nice to have that kind of reach,” Aunalee said. “We’re assuming it’s because people saw us on the SWAIA website. It increased our visibility in the U.S.”

The Good sisters were really looking forward to being at the Santa Fe Indian Market in person and taking in the whole scene, however.

“It was disappointing for sure, but amazing that they went ahead and did such an organized event online,” Aunalee said.

Passamaquoddy basket maker Jeremy Frey has won top prizes on multiple occasions at Santa Fe Indian Market and the Heard. He’s an old hand at Native art markets, but is sitting out most of this year to focus on building inventory and catching up on orders. He was part of Santa Fe Indian Market as far as having an Artspan site, but didn’t enter any baskets in the juried competition.

“Normally I have great stories, but this year I’m not really doing anything exciting,” Frey said. “Generally I would have a giant piece to compete with, but I don’t feel like photos of my work would do it justice.”

The lack of live personal interaction has also made Frey reluctant to invest a lot of time and work in the virtual market scene.

“It’s always fun to introduce your work to someone for the first time. We do a lot of teaching at the shows about where we come from and how our work relates to history and our people. We answer thousands of questions,” Frey said. “There’s no replacing the live show. I don’t think virtual markets are going to replace live markets, they’ll just augment them.”

Frey’s Penobscot basketmaker wife, Ganessa, feels having a physical presence gives her an advantage.

“I’m not as known, so I don’t know how much traffic my website will get,” she said. “But when Jeremy and I are at the same table, I can usually talk people into buying my baskets.”

Aside from losing that profitable proximity to her husband, the self-described “homebody” is all for virtual art markets.

“I actually like it, because honestly I don’t like to travel. It’s very stressful for me to find babysitters. It’s just a huge thing for me to have to do, so this works out for me better,” she said. “I actually love it.”

‘You are all guinea pigs’

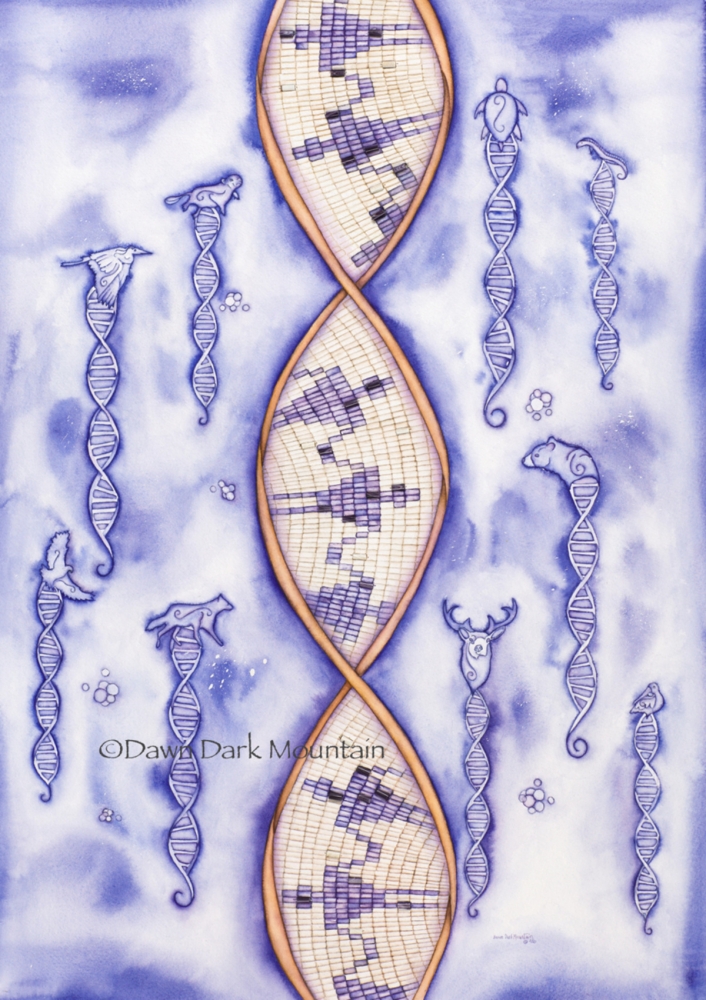

A multimedia piece about Indigenous identity by Oneida watercolorist Dawn Dark Mountain. (Dawn Dark Mountain)From her new, self-styled garage gallery, Oneida watercolorist Dawn Dark Mountain introduced a Santa Fe Indian Market virtual booth hopper from Las Vegas to herself and her art.

A multimedia piece about Indigenous identity by Oneida watercolorist Dawn Dark Mountain. (Dawn Dark Mountain)From her new, self-styled garage gallery, Oneida watercolorist Dawn Dark Mountain introduced a Santa Fe Indian Market virtual booth hopper from Las Vegas to herself and her art.

“This is me. More importantly this is my work,” she said. Dark Mountain then pointed to “Who We Are,” a piece with wampum beads sewn in, and floating DNA strands topped with clan animals.

“This piece is about DNA and cultural identity,” she explained.

“I saw that one hanging there. It’s very moving,” her virtual guest responded.

“I’m saying our cultural identity is not identified by our DNA or our blood quantum, but rather by our ties to our community and our culture and our ancestors, and those are much more important components,” Dark Mountain explained.

“Being mixed I appreciate that very, very much,” the guest said. “Could you move in on it a little bit closer?”

Virtual Booth Hopping took place over the Santa Fe Indian Market’s third weekend, and Dark Mountain’s experience demonstrated what a powerful learning and relationship-building tool it could be.

In a span of about 15 minutes, Dark Mountain described several of her pieces in-depth and made a meaningful connection with her guest, who eventually exited her virtual booth to shop Dark Mountain’s e-commerce site.

As a whole, Virtual Booth Hopping was a mixed bag. There were shining moments of enriching interaction, but they were few and far between, according to several of the artists who spoke with Native News Online.

“I haven't had a whole lot of visitors all weekend,” Dark Mountain said during her downtime.

About 50 artists indulged in Virtual Booth Hopping, and Dark Mountain and others said it was probably the most hastily thrown together and least promoted part of the market.

But they understand that it would be impossible for SWAIA to perfectly execute every single element of the virtual fair.

“I don’t fault them for not getting this part right,” Dark Mountain said, adding that one of the great things to come out of Virtual Booth Hopping was having a reason to set up an attractive display area. These days, she’s using the set-up in her garage to meet local customers, and has already sold additional work as a result.

“I wouldn’t have done that otherwise,” Dark Mountain said.

Some artists weren’t well versed enough in Zoom to make it work. But the artists were very resourceful and determined, and a few worked around it by presenting live on their Facebook pages instead.

“You almost need to have a Zoom class offered from SWAIA,” Clarkson said. She bypassed Zoom completely, and chose to draw virtual visitors into her world via Facebook Live.

With humor and humility, Clarkson addressed the experimental nature of her presentation.

“You’re all guinea pigs,” Clarkson declared to viewers at the start of her broadcast. “I’m glad you’re all here. I’ve never done a live video in my life, so I have no idea what I’m actually doing. Does my head look really big now?”

For the next two hours, Clarkson reacted to dozens of commenters, demonstrated her technique while working on paintings-in-progress, and was occasionally interrupted by her dogs.

Clarkson got a kick, along with some serious cash, out of the Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market, and is looking forward to November’s virtual version of the Autry Museum of the American West’s American Indian Arts Marketplace.

“I’m very encouraged that we can find another venue to present our art to people,” Clarkson said. “It worked out well for me and I would do it again in a heartbeat.”

More Stories Like This

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Takes Top Emerging Artist Apprentices to Phoenix for Artistic Exploration and Cultural ImmersionFrom Dishwasher to Award-Winning Chef: Laguna Pueblo's Josh Aragon Serves Up Albuquerque's Best Green Chile Stew

Rob Reiner's Final Work as Producer Appears to Address MMIP Crisis

Vision Maker Media Honors MacDonald Siblings With 2025 Frank Blythe Award

First Tribally Owned Gallery in Tulsa Debuts ‘Mvskokvlke: Road of Strength’

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher