When 13-year-old Gia Mendoza began seventh grade last year at Ignacio Middle School in southwest Colorado, she noticed something was missing from the bathrooms.

While the school regularly provided toilet paper, soap and paper towels, free and comfortable period products were noticeably absent.

“Our school didn’t really talk about it,” Mendoza, a descendant of the Chiricahua Nation, told Native News Online.

Ignacio Middle School had only cardboard applicator tampons that cost a quarter each from bathroom vending machines, making the products undesirable and harder to access.

Girls — including herself — were missing school because of painful periods and a lack of access to free supplies at school.

“It was something to be hidden, but it really shouldn’t be,” Mendoza said. “I was like, ‘I don’t know why people don’t talk about this.’”

Now, in partnership with The Kwek Society, a Native-led nonprofit that provides period products and educational materials to Native American girls and their communities, Mendoza is leading the charge in her school to de-stigmatize the period experience.

Ignacio Middle School is one of 89 schools across North America that has partnered with The Kwek Society to end “period poverty,” or inadequate access to menstrual hygiene tools and education.

Eva Marie Carney (Citizen Potawatomi Nation) founded The Kwek Society in 2018, after realizing that many Native women were impacted by period poverty, but their voices were largely absent from conversations around it. Kwek means “women” in the Potawatomi language.

A 2021 study by THINX and PERIOD found that nearly a quarter of all students are impacted by period poverty, particularly students of color.

“I really don’t think this is a Native problem,” Carney said. “This is a poverty problem.”

According to the school’s website, Ignacio Middle School had 161 enrolled students from 2020-2021. Of them, nearly a quarter are white, a quarter are Native, and about half are Hispanic. More than half of the students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch through a federal program for children of low-income families.

“What seems very clear to me is that any student that qualifies for free or reduced-price lunch in a public school is at risk for period poverty because the products are just so expensive,” Carney said. “And they aren’t typically available through food banks, or through schools or public facilities. To me, it’s just a crime.”

Since 2018, The Kwek Society has donated more than 1.2 million period products to schools and other partner organizations. Those donations have helped increase the availability of period products and take pressure off school staff and administrators, who have historically spent personal funds on period supplies for their students.

At the Navajo Preparatory School in Farmington, N.M., where some students live on campus, school nurse Kandince Duvall (Diné) said staff members would often buy pads and tampons for students since the school’s budget only covered basic products.

“It’s allowed me to build a better relationship with my students, as well as staff,” Duvall told Native News Online. “They’re so appreciative, and it’s built a sense of trust and enhanced our relationship.”

The Kwek Society is also flipping the script to stress “dignity and celebration” over feelings of shame and embarrassment around young women coming of age. The organization has created an online resource to collect traditional teachings around menstruation — traditionally referred to by some as their “moon time” — to empower young women.

Carney created “moon time bags” filled with menstruation supplies to distribute to every girl The Kwek Society serves.

“I think it’s really just a matter of dignity and celebration and good health,” Carney said. “In the perfect world, none of this would be required, but this is where we are right now.”

Jeanine Brooks, a social worker at the Keet Gooshi Heen Elementary School in Sitka, Alaska, has seen a difference in student attitudes since gaining access to educational materials from The Kwek Society.

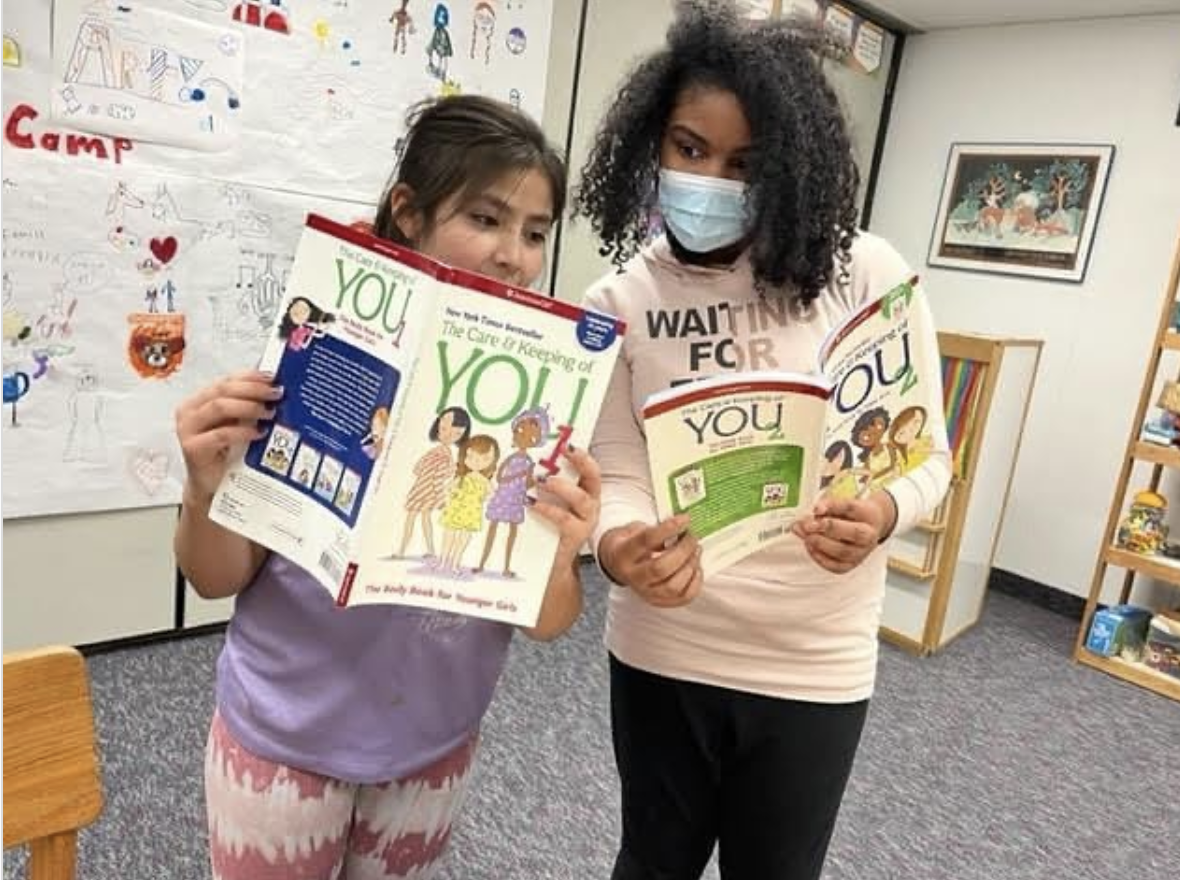

Students at Keet Gooshi Heen Elementary School in Sitka, Alaska, receive period products and resources from The Kwek Society. (The Kwek Society)

Students at Keet Gooshi Heen Elementary School in Sitka, Alaska, receive period products and resources from The Kwek Society. (The Kwek Society)

“It transformed my office and the puberty education that I did for kids,” Brooks told Native News Online. “Immediately, I had girls feeling comfortable coming in and getting period products, talking to me about starting their periods, reading these books with me, borrowing the book. It was incredible how within weeks, The Kwek Society had transformed my social work program, and really the way that our school created access for students.”

While The Kwek Society is aimed at targeting the result of period poverty, other organizations are focused on advocating for change in state legislation that taxes the sale of period products, often called the “tampon tax.”

According to Allied for Period Supplies, an organization leading the charge to end the tampon tax, about half of the states charge a sales tax of between 4% and 7% for period products. And that’s while 33 states and Washington D.C., exempt food from their general sales tax.

People who menstruate require around 40-period products per cycle, according to Allied for Period Supplies.

“The elimination of sales tax on these basic necessities helps all people who menstruate better afford the period products they require to reach their full potential,” their website reads.

Since 2020, ten states have ended their tax on period products: Washington, Vermont, Maine, Michigan, Louisiana, New Mexico, Nebraska, Colorado, Iowa and Virginia.

Additionally, since 2018, 17 states and Washington, D.C., have passed legislation to ensure students who menstruate have free access to period products while in school. Colorado — Mendoza’s home state — was one of them, appropriating $100,000 in 2021 to fund the act.

“Everyone comes from a woman,” Mendoza said. “So it’s good to be able to respect that.”

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

End of Enhanced Obamacare Subsidies Puts Tribal Health Lifeline at RiskSanta Ynez Tribal Health Clinic to Host Free Pediatric Dental Clinic

Rez Vet Earns Global Recognition for Serving Navajo Nation's Animals

Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby leads groundbreaking for pediatric clinic

Cherokee Nation Eyes $4 Million Transitional Housing Program