Donald Trump granted pardons to 73 individuals on his final day of presidency, and commuted the sentence of another 70, including Lavonne Roach of the Oglala Sioux Tribe (Lakota Sioux), who has been serving a 30-year sentence for a non-violent drug charge.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, a commutation reduces a sentence, but does not imply innocence or remove civil disabilities, such as the right to vote or to hold public office. A pardon does not signify innocence, but gives the pardoned back their right to vote and to serve on juries, among other freedoms and privileges.

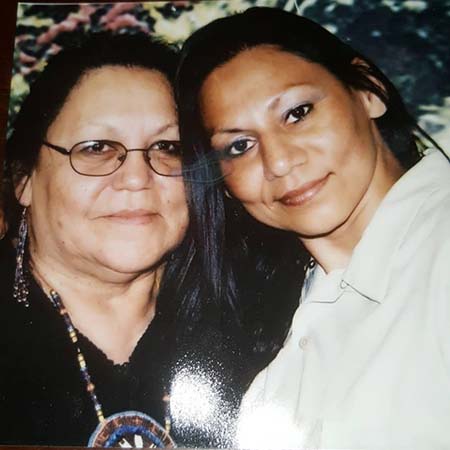

“My mom was always somebody with a big heart who happened to have gone down the wrong path with the wrong people,” Roach’s daughter, Clarissa Brown, told Native News Online. Brown, 40, has spent more than half of her life with her mother behind bars. She has followed in her now-deceased grandparents’ efforts to free her mother by soliciting support from lawmakers, lawyers and advocates.

“I believe that she should have done some time because of the crime. But never in my life did I think that they would ever sentence her to 30 years, and I never thought she would actually do over half of that time,” Brown said.

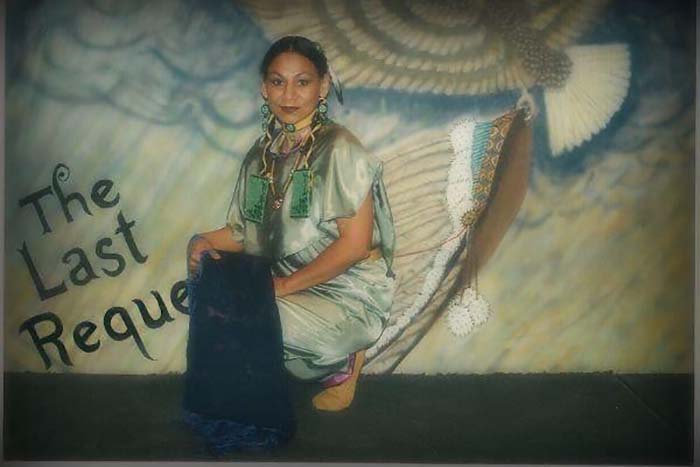

Lavonne Roach poses in traditional Tribal regalia for a powwow within prison in the early 2000s.

Lavonne Roach poses in traditional Tribal regalia for a powwow within prison in the early 2000s.

Roach, according to a White House press release, had a “model exemplary prison record.” While serving her sentence for conspiracy to distribute meth at a federal prison in West Virginia, she enrolled in college courses, became certified as a paralegal and administrative assistant, and tutored other inmates. She mentored at-risk teens, and led a Native American talking circle, her daughter said.

“Finally, mission accomplished,” said Amy Povah, founder of the nonprofit CAN-DO, which advocated for clemency for all non-violent drug offenders. Povah has worked with Roach’s family to secure her release for more than a decade.

Roach was slated to receive clemency under the Obama administration, but her clemency petition was passed over. She had been granted a compassionate release — or early release granted to model inmates — a week earlier for medical reasons, but under such a release would have been saddled with a five year probationary period. Instead, Roach will walk free for the first time in 23 years, supported by her three children, 11 grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Povah said support from Roach’s prosecutor, Mark Vargo, likely played a large role in securing her freedom. Vargo wrote a letter directly to President Trump, dated March 11, advocating for Roach’s full clemency.

“I feel that she is no longer the same person who was sentenced 22 years ago and it would be appropriate that she be released back into the community and to her family,” wrote Vargo, who is Pennington County State’s Attorney. “Her recognition that her own drug addition led her to federal prison is important, as are the strides that she has made to live a sober life: completing two drug treatment programs along with numerous other educational opportunities with the prison system.”

Native Americans are overrepresented in the criminal justice system, with an incarceration rate that is over four times the rate of white people, according to the National Council on Crime and Delinquency. But Roach is among a small number pardoned by exiting President Trump.

Crystal Munoz, a Navajo mother who spent 12 years in prison for having played a small role in a marajuna smuggling ring, was pardoned by Trump last February.

“Natives get overlooked and left behind a lot of times because a lot of us are very… peaceful and not aggressive, so we kind of get put on a back burner,” Brown said. “If anybody out there has someone in prison, they just can’t give up.”

Brown’s sister will pick up their mother from prison on Wednesday. She has organized a fundraiser to accept donations for Roach, who will be leaving prison with just the clothes on her back.

“She wants to first spend time with her family, her grandchildren,” Brown said of her mother. “Especially in the Native community. She wants to share her story… so people don't suffer the same fate as she did.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsZuni Youth Enrichment Project Announces Family Engagement Night and Spring Break Youth Programming

Next on Native Bidaské: Leonard Peltier Reflects on His First Year After Prison

Deb Haaland Rolls Out Affordability Agenda in Albuquerque

Boys & Girls Clubs and BIE MOU Signing at National Days of Advocacy

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher