- Details

- By Neely Bardwell

Native Vote 2024. New research from the University of Utah’s College of Social & Behavioral Science assessing the benefits and alleged costs of ballot collection on Indian reservations debunks common misconceptions about ballot collection.

Native American communities often rely on common misconceptions due to socioeconomic and logistical challenges.

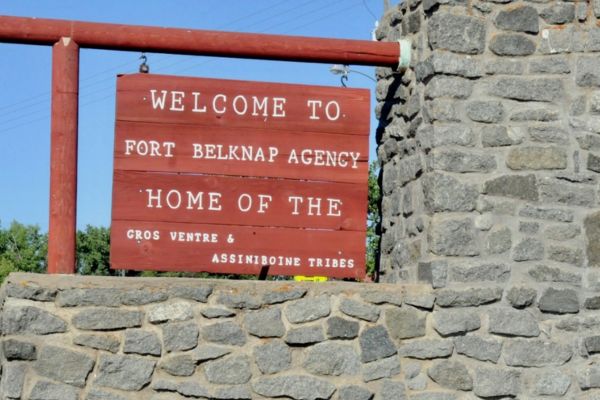

The research, focusing on Indian reservations in Montana and other Western states, appears in the July edition of the “American Indian Culture and Research Journal.” Authors Daniel McCool, a professor emeritus in the Department of Political Science, and Weston McCool, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Anthropology, are a father-son duo.

Ballot collection, sometimes negatively referred to by critics as “ballot harvesting,” is the practice of someone other than the voter turning in completed ballots to a post office or ballot box. With the rising popularity of mail-in voting, ballot collection is becoming increasingly popular.

By examining trends in vote-by-mail programs, socioeconomic variables, distance to polling stations and mail locations, and U.S. Postal Service delivery efficiency on reservations, the McCool team documented how ballot collection improves the voting experience of Natives.

In an attempt to help Native Americans who often lack home mail service, nonprofits such as Western Native Voice have collectors deliver tribal members’ ballots to a post office or polling station that are often miles from their homes. These ballot collectors are supervised by tribal governments and other nonprofits.

“They collected hundreds of ballots from Native Americans who live in very, very remote places,” Daniel McCool said originally to At the U. “The reason why these native voters were taking advantage of the ballot collection service was because it’s very difficult for them to overcome those long distances and the poor transportation.”

On reservations, where access to polling places and reliable mail services can be limited, ballot collection ensures community members can exercise their right to vote without undue burden.

Due to fear of fraud, legislatures in Utah and three other Western states have tried to ban the practice. Utah banned ballot collection by third parties under an election reform law unanimously passed in 2020. Nineteen states allowed only the voter, a family member or a caregiver to turn in a ballot during the study’s time frame. Four of these states, Arizona, Oklahoma, New Mexico and Nevada, have substantial Native American populations.

The statistical analysis conducted found no evidence to support allegations that ballot collection leads to voter fraud. The McCools used data collected by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank behind Project 2025.

“The evidence is actually collected by the conservative think tank, the Heritage Foundation,” McCool said. “We use their data to indicate that there’s no voter fraud associated with ballot collection.

The Heritage Foundation’s database documents 1,850 cases of proven voter fraud, which resulted in convictions, going back to 1980 for all elections surveyed. Using that data, the McCool team found that the frequency of voter fraud is .00006%. That is six cases of proven fraud for every 10 million votes cast in the United States

“The problem is not voter fraud,” McCool said. “The problem is the fraud about voter fraud.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsFirst Peoples Fund Announces 2026 Cultural Capital Fellows

Deb Haaland Campaign Responds to Why Her Name is in the Epstein Files

Cadiz, Inc. Announces EPA Selection of Mojave Groundwater Bank Northern Pipeline Project for WIFIA Loan Application

Jesse Jackson, Who Bridged Civil Rights Struggles for Blacks and Native Americans, Dies at 84

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher