- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

Alaska Native artists have been mask-making like mad since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some of their ingeniously indigenized masks have already become highly significant signs of the times. Major museums in Washington D.C. and Seattle have acquired at least three Alaska Native-made masks made in the past few months.

In late April, The Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington D.C. came calling for Vicki Soboleff’s (Haida) woven cedar mask, “Just Ovoid It,” a few days after it appeared in First American Art Magazine’s online exhibition called “Masked Heroes.”

Just Ovoid It Deluxe, a yellow cedar mask woven by Vicki Soboleff was purchased for the Smithsonian American Art Museum Collection. (Photo: Vicki Soboleff)

Just Ovoid It Deluxe, a yellow cedar mask woven by Vicki Soboleff was purchased for the Smithsonian American Art Museum Collection. (Photo: Vicki Soboleff)

The Burke Museum in Seattle also recently purchased two unique masks made by Alaska Natives that also appeared in “Masked Heroes.”

Lily Hope (Tlingit) made one of the masks using the complex ancient Chilkat weaving technique, named after the Chilkat tribe of Klukwan, Alaska. Primarily used to create robes and blankets, the Chilkat style is distinguished by the curvilinear shapes woven into the items. Hope said Chilkat blankets have always chronicled the eras in which they are made.

Her Chilkat Protector mask is made from thigh-spun merino and cedar bark warp, merino weft yarns, ermine tails and tin cones.

The Chilkat Protector mask by master weaver Lily Hope has been acquired by the Burke Museum in Seattle. (Photo: Sydney Akagi Photography)

The Chilkat Protector mask by master weaver Lily Hope has been acquired by the Burke Museum in Seattle. (Photo: Sydney Akagi Photography)

The museum also purchased a seal fur mask adorned with glass beads made by Crystal Worl (Tlingit /Athabascan/Yupik). Worl said she was “stoked” that the Burke Museum was interested in her work and, in general, what artists are doing with masks.

“What a way to document what artists are doing in a time like this,” Worl said. “I’ve really just discovered that now is the time for artists to really step into our role as people who speak up in our community and represent human needs.”

It’s serious art for a crucial cause, but Alaska Natives are adding plenty of playfulness to the way they’re making masks and motivating others to get on board.

All three of the museum-bound masks also appeared in May’s online Alaska Face Mask Fashion Show, which virtually tapped into the trend and drew submissions from more than 80 artists.

With Zoom replacing the runway, Alaska Native artists Erin Tripp (Tlingit) and Vera Starbard (Tlingit/Dena'ina/Athabascan) hosted the virtual event along with a panel of judges.

“We already have some really strong mask traditions and masks are part of our culture,” Starbard said. “Even in this time of crisis, we are able to create art and beautiful things from it.”

Broadcast on the Alaska Native Virtual Gathering Place, a Facebook group Starbard created to maintain a sense of togetherness during quarantine, the show revealed face coverings—some strictly art, some practical, and some both—bursting with Native designs, techniques and materials.

Starbard, Tripp and the judges commented over a slideshow exhibiting exquisite hand-beading and hand-painting, marine mammal furs, cedar, dried berries, ancient weaving techniques, symbols including copper Tinaas, a shield-like Southeast Alaska symbol of good fortune, and a flock of formline, the signature Northwest Coast Native style defined by ovoids, U-shapes and S-shapes.

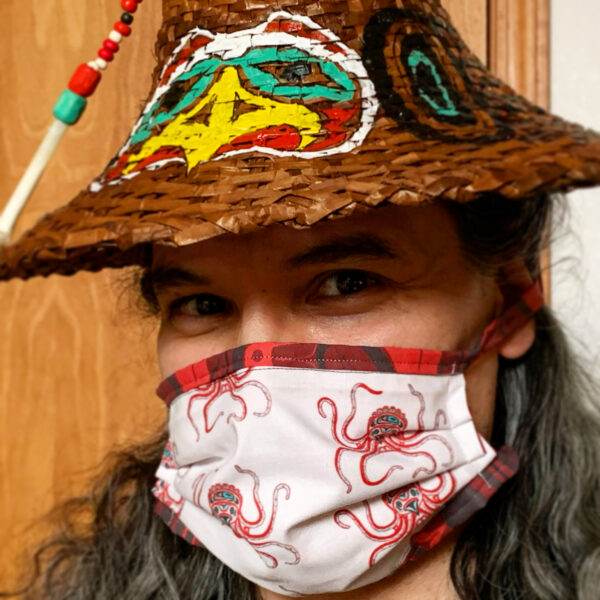

There was also a modeling category where Alaska Natives showed off the masks they’ve been wearing in a series of slides. Some modeled self-made masks, and others sported masks they bought.

“The online mask show was brilliantly planned. It was the most efficient and safely distanced way to showcase our Native Artists’ current work. I was honored to be included,” said Lily Hope. Her striking blue, white and black Chilkat Protector mask won Best in Show.

“Alaska Natives are involved in making masks because it’s built into our DNA to take care of each other,” Hope said. “We have survived genocide, internment, government-issued burning of our villages, boarding schools, and federal controls of our land, natural resources and waters. We are making masks because we are fierce resilient indigenous peoples of Alaska. It tells the world we are still here. We are thriving. “

Formline and Function

Vera Starbard is a pioneer of the Alaska COVID-19 mask movement, and her fully involved family embodies values Native Alaska mask makers share: a commitment to adapting and sharpening Native art skills, showing up for front-line workers and vulnerable Elders, and having fun in the process.

The Starbard operation spans several states. Vera’s father Don draws the formline designs and sends them from his home in Washington to Vera in Anchorage, who then digitizes the art and transfers it on to fabric. The masks, the vast majority of which are donated, then go out across the state and the country.

“Some of the first masks I made were for my grandparents and the Elder program here in Anchorage. I still have 25 that are being sent to an Elder program in the Navajo Nation,” Starbard said. “People were talking about the elders first as far as protecting them. Many masks were quickly made for the elders… a Native Elder recently gave me dozens of yards of fabric to make masks for Navajo Nation and Hopi Elders down south. ”

Vera Starbard transfers her father Don's formline designs on to fabric for their protective face masks. Vera's husband, Joe, models a formline image of the mythical monstrous sea creature known as the Devilfish. (Courtesy photo).

Vera Starbard transfers her father Don's formline designs on to fabric for their protective face masks. Vera's husband, Joe, models a formline image of the mythical monstrous sea creature known as the Devilfish. (Courtesy photo).

Vera and many other Alaska mask-makers are donating their work to frontline workers and other folks in desperate need of masks across the nation

Making effective and attractive masks is a task Don Starbard relishes, and he is enjoying experimenting with formline designs.

“Part of formline technique is learning to fill a space, whether it’s a canoe or a drum, and these masks were a new shape for us,” Don Starbard said. “We see it as a little bit of a challenge to fill that as artistically as we can. Artists are creating and coming up with some awesome fills for the space available.”

Alaska Native mask artists are also having fun integrating identity into their masks.

“The Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian, we love to display our moieties and crests and show who we are,” Don Starbard said. “This was a good opportunity for that.”

A few of the Starbard masks star the Devilfish, a mythical monstrous octopus. Vera, also the playwright in residence at Juneau’s Perseverance Theatre, wrote a popular play called “Devilfish” and several of her dad’s promotional designs have made their way onto the family’s masks.

“The Devilfish is a family crest for my daughter Vera and her mother,” Don Starbard said.

Formline is the specialty of Southeast Alaska Natives. The region, including Ketchikan, Sitka and Juneau, is teeming with totem poles, canoes, carved masks, company logos and just about every form of formline expression imaginable.

So it makes perfect sense that Juneau, designers and vendors have formline masks covered.

At the gift shop for Sealaska Heritage Institute, an arts nonprofit representing Alaska Native tribes, protective cotton formline masks designed by Canadian artist Kelvin Robinson (Nuxalk) are on sale for $20 each and available in three colors.

Right across the street at Trickster Company boutique, sleek and wearable formline fashion statement masks for $27.50 are among the modern clothes and accessories meshed with Alaska Native art — when they can keep them on the shelves.

“We just sold out of them. They sold out really quick,” said Trickster co-owner Crystal Worl, who designed the masks. Worl offers hopeful news: “We have more Trickster masks on the way and a new design.”

The masks that flew off the shelves were red and black with a cleverly detailed formline eagle, five layers of protection, a replaceable filter, adjustable straps and a wire nose bridge. Worl named the mask Breathe.

This formline eagle mask from Juneau, Alaska-based Trickster Company has five protective layers, a replaceable filter, wire nose bridge and adjustable straps. Currently sold out, but will be back in stock soon.

This formline eagle mask from Juneau, Alaska-based Trickster Company has five protective layers, a replaceable filter, wire nose bridge and adjustable straps. Currently sold out, but will be back in stock soon.

“If you look closely you’ll see his beak is open and there’s a fine line that comes out from the mouth and the fine line signifies the intake of oxygen,” Worl said. “It’s just kind of wild that I named it Breathe. This was before the rallies and protests around George Floyd. I’ve been using that mask for when I participate in the marches and have seen other people wearing them. It made me really proud to see community members wanting to wear these indigenous designs. That was cool to see.”

Natural Women

Since Worl shifted into mask-making mode in March, she’s been reflecting on the meanings behind the masks.

“Indigenous people in Alaska in general have used masks for ceremonies, for dancing, for storytelling, for passing on knowledge and they definitely carry encoded values and stories that are passed onto the next generation,” she said. “It’s kind of interesting trying to indigenize these protective masks. (They can) deliver a message of still being connected to the land, but still being contemporary.”

Worl’s mask that is bound for the Burke Museum is strongly tethered to the sea and the art of skin sewing. The stylish seal fur face covering also naturally represents Worl — a fierce, resourceful, modern artist steeped in Alaska Native traditions — who skillfully balances both sides.

“The fur was from a seal I harvested. I have training in skin sewing, so I sewed the seal fur together and beaded the edges and it just turned out really great,” she said. “I just made the bias tape from scrap fabric because the time I made this was at the beginning of the pandemic and all the stores were out of elastic bands, they were out of bias tape, they were totally wiped out, so I just fabricated it myself.”

Vicki Soboleff (Haida), also looked to the land for her protective masks.

Fashioned from red and yellow cedar, Soboleff’s masks are functional art pieces, complete with handmade felt filters. A variety can be found for around $75 each on the Soboleff Selections page on Facebook.

A set of woven cedar protective masks for the whole family, made by Vicki Soboleff. All of the masks come with filters. (Courtesy photo)

A set of woven cedar protective masks for the whole family, made by Vicki Soboleff. All of the masks come with filters. (Courtesy photo)

Inspired by a friend who was making cotton protective masks, Soboleff, who can’t sew, pondered how she could create a great indigenized mask. Quickly, she realized she already had all the necessary ingredients: the will and skill to weave and piles of cedar from Washington and Southeast Alaska.

“The (idea to use) red and yellow cedar came to me and I got up and wove the first one,” said Soboleff, who also works as a finance accounting manager at The Tulalip Tribes. “I also know that cedar has many medicinal properties so I felt a cedar mask as an additional barrier was better than a cotton face mask alone.

“Many masks are being made due to the cultural value of respect and protection of elders and those who are frail. Survival instincts are strong with indigenous people.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsNavajo Nation Mourns the Passing of Former Vice President Rex Lee Jim

Deb Haaland Earns Endorsement From Communications Workers of America Local 7076

University Soccer Standout Leads by Example

Two Native Americans Named to Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee's“Red to Blue” Program

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher