- Details

- By Rich Tupica

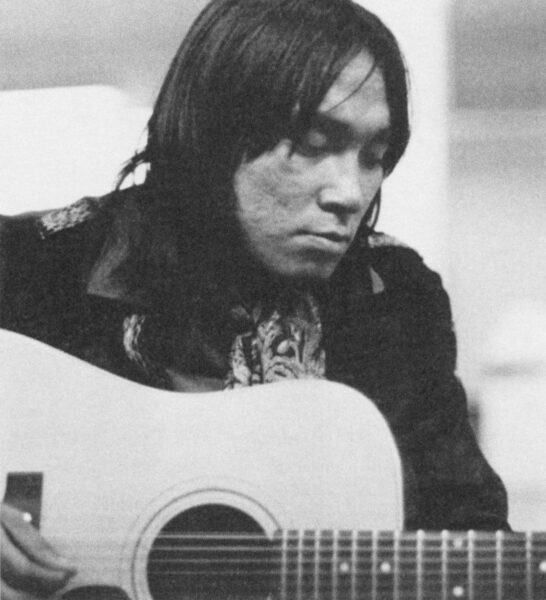

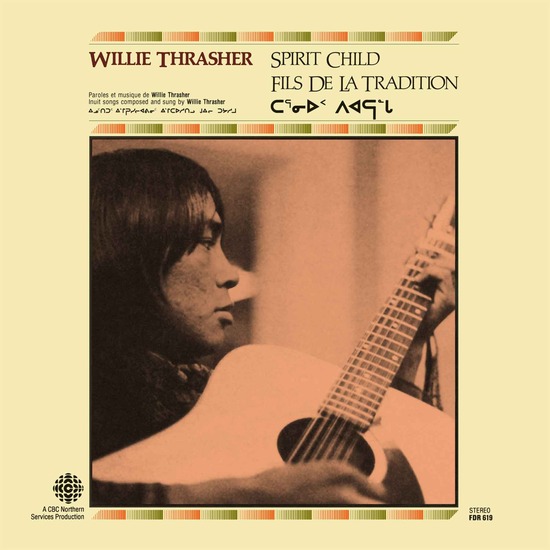

After spending a bulk of the 1970s floating across his native Canada and the United States, performing his pensive brand of Indigenous folk rock, singer-songwriter Willie Thrasher went into the studio and recorded his masterpiece, 1981’s Spirit Child LP. It's a poetic, moody tracklist that spans genres. It’s obviously inspired by his Inuit culture, but also his love of rock ‘n roll and pop music. Those elements, and the passion behind it, created a genuine, emotionally raw hybrid. When songs truly come from the heart, it’s evident, and it’s clear Thrasher was mining inspiration from the mysterious authentic place all songwriters aspire to reach one day, though most never will. Rustic songs on Spirit Child, like “Beautiful,” echo the classic 1960s-era folk-rock records like The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo or The Band’s Music from the Big Pink. But what sets Thrasher apart is his ability to clearly and unapologetically pay homage to his people and the earth.

Thrasher delves deep into woods, especially on tracks like “Wolves Don’t Live By the Rules,” which sonically transports you to a hilly, wooded trail, as the tune hurriedly scampers along to sporadic howls. His experimental nature stays on display throughout both sides of this album. Tunes like “Old Man Carver” twists the album into psychedelic loner-folk territory that both Neil Young and Bob Dylan would tip their hats to.

With a stack of songs so well-crafted, it’s hard to say which track is “best,” but that title may have to go to “Silent Inuit.” The sullen four-and-a-half minute jangly guitar ballad is layered with a female co-vocal, giving it an otherworldly abstract-pop vibe — similar to duos like Serge Gainsbourg & Brigitte Bardot or Lee Hazelwood & Nancy Sinatra.

"Silent Inuit

Fall away

From home

All alone

Travelling with the wind

Sleeping with the moon

Letting the great spirit walk over you

Silent Inuit

Please don’t cry

You’ll be home someday"

-lyrics by Willie Thrasher

While it didn’t become a national sensation, “Silent Inuit” did score some regional airplay at the time of its release, but that’s where the minimal commercial fanfare stopped. “We travelled and heard our songs a little on the radio,” Thrasher recalled years later. “Someone would say they heard ‘Eskimo Named Johnny’ or ‘Spirit Child’ on the radio and were really proud of me. So back then it was really tough to push our album because we had no agent, no manager. It was just financed by CBC and had nothing else to push it.”

The 1981 “Spirit Child” album by Inuk singer-songwriter Willie Trasher is brilliant folk-rock with an Indigenous heartbeat.

The 1981 “Spirit Child” album by Inuk singer-songwriter Willie Trasher is brilliant folk-rock with an Indigenous heartbeat.

The record, originally released by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), indeed slid into obscurity, but Thrasher kept on and, many years later, it paid off. In 2015, his legacy was preserved when Light In the Attic Records reissued an expanded edition of his Spirit Child album and also included him on Native North America (Vol. 1): Aboriginal Folk, Rock, and Country 1966-1985, a stellar 2014 compilation spotlighting largely overlooked Indigenous troubadours. (Listen to the entire collection on a YouTube playlist, here). Looking back on Thrasher’s life, it’s not hard to see where the inspiration for Spirit Child came from. He was born in 1948 in Aklavik, a hamlet located in the Inuvik region of the Northwest Territories, Canada.

At five years of age, Thrasher was taken from his family and sent to a residential school. The already troubling time was exacerbated when he was forbidden to practice his Inuvialuit culture due to a shameful initiative by the Canadian government to assimilate Indigenous people into mainstream society. Thrasher began to look to music for solace and by the mid-’60s was drumming for The Cordells, one of the first Inuit rock bands. After a stranger recommended the band should dig deeper into their Aboriginal roots, and look away from the pop charts, Thrasher had an epiphany. After The Cordells split up, a 19-year old Thrasher picked up a guitar and started to write songs about his Inuvialuit heritage, even after losing a portion of his left middle finger in a work accident. With nothing holding him back and his guitar case in hand, he hit the road. The young songster spent the 1970s and ‘80s as a musical vagabond, travelling from town-to-town, belting out his batch of honest songs for small crowds.

However, since his sudden boost of critical notoriety following his more recent deal with Light in the Attic Records, Thrasher has enjoyed the well-deserved acclaim he should’ve received years ago. In a 2015 interview, he said he was thrilled to introduce people to his songbook to new fans and bigger crowds, including high-profile festival spots at Austin Psych Fest and Levitation Vancouver. “It’s different and really weird because I remember playing those songs 30 years ago,” he told Vice. “And 30 years ago, those songs were new, lively. I had long hair and we travelled all over under the great Northern Lights, plus doing festivals in Montreal, Toronto, Edmonton, Winnipeg, the States. We were really enjoying our music so much. And now that feeling inside is coming out again. It gives me lots of energy to perform again. Plus, my voice has changed since then. It’s better now, and my guitar playing is better controlled now.” Today, Thrasher lives in the town of Nanaimo, B.C., where he, of course, continues to keep it real. He performs as a city sanctioned busker with his partner Linda Saddleback.

So if you’re walking down the streets of Nanaimo and happen to hear the words of “Spirit Child” reverberating in the wind, look twice, because it just might be the genius songwriter himself, singing it where it was meant to be sung — under the open sky.

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsNavajo Nation Mourns the Passing of Former Vice President Rex Lee Jim

Deb Haaland Earns Endorsement From Communications Workers of America Local 7076

University Soccer Standout Leads by Example

Two Native Americans Named to Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee's“Red to Blue” Program

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher