- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

Indian Country lost a social advocate, a brain, and a fierce defender of Native American rights on Wednesday, May 19, when Cinda Hughes (Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma) died in her home in Alexandria, Virginia, after a yearlong battle with cancer. She was 59.

Hughes is remembered by her family and friends as passionate, tough, and one who “lived her life at 90 mph in a 35 mph zone.” She leaves behind a mother, four siblings, and eight nieces and nephews.

Originally from Anadarko, Okla., Hughes worked from the time she was in high school to advocate for rights of Native Americans with disabilities. Hughes herself was a quadriplegic—she was born with a condition that impacted the use and growth of her limbs, rendering her wheelchair dependent—which contributed to her dedication to advocacy work.

“Her love for knowledge was voracious,” Hughes' mother, Gayle Roulain told Native News Online. “She said to me, ‘I may not be able to be as active in school as all the other kids, but I can be active in academia.’” Hughes was nominated student body president, served as a member of the National Honor Society, and was appointed by the United States Secretary of the Interior to the Bureau of Indian Affairs Advisory Council on Exceptional Children, where she advocated for children with disabilities.

Naturally, Hughes' professional life began to take the shape of the advocacy work she pursued personally. After graduating Anadarko High School in 1980, then going on to study at Brigham Young University and Oklahoma University, Hughes' first job was an aide at the Oklahoma State Legislature.

Her career also included jobs as the Program Specialist at Office of Disability Employment Policy, Dept. of Labor; Legislative Associate for the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI); legislative affairs director at CANAR, an organization providing vocational rehabilitation and training to Indigenous peoples living with disabilities; and, most recently, Tribal Relations Specialist at the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“She wasn't just an advocate,” said Cinda’s colleague-turned-friend, Randy Slikkers. “She was like a superhero kind of advocate.” Slikkers said one of his friend’s proudest moments was helping pass the Navajo Code Talkers bill at NCAI, which honored all 29 code talkers who assisted in World War II.

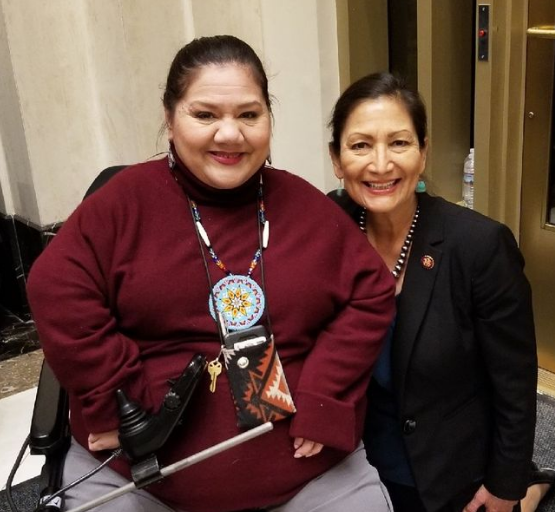

Hughes’ brother, Phillip Roulain, said his sister was so well connected, she could enter into any room and know somebody. On her Facebook page, photos depict her with prominent political figures in Washington, D.C. such as former Secretary of State and First Lady Hillary Clinton, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi.

“She was honored and revered by everyone that she met,” Hughes’ brother said. “She would work a room in the most professional, schmoozy way.”

Hughes' mother said their family’s motto was: “win some, lose some, some get rained out, but you show up to play them all.”

Friends and family echoed that, despite everyday life presenting a greater challenge to Hughes, she met her experiences with strength and fortitude. Her mother recounted a visit the two paid to New Mexico where Hughes was invited to speak at a conference. Companies in attendance were discussing a percentage of their employment going to Natives with disabilities.

When the pair arrived, it was raining and sleeting.

Because of Albuquerque’s poor infrastructure for wheelchair accessibility, Cinda had to drive her motorized wheelchair two miles in the sleet while her mother took the shuttle to the conference hall.

“She drove without an umbrella and without anything but just her coat,” Gayle Roulain said. ‘When electric wheelchairs— the control mechanism gets damp—it just locks. So her chair locked in the middle of the street.” Two men pushed Cinda out of the street to the bus stop. “I said, ‘You know what, I think you're taking this a little far. I don't think we should go.’ And she said ‘No, mom. If you want to not go, you're welcome to not go.”

“That’s her tenacity,” Roulin said of her daughter. “That’s what she did until she couldn’t anymore.”

Although Cinda’s passions bled into her professional life, her family said she was also interested in singing, movies, music (except country music) and spending time with her nieces and nephews. Slikkers said she could quote almost any movie.

A die-hard Steve Miller Band fan, Hughes would often travel to see live music. Once, according to band member Kenny Lee Lewis, she approached the band after their show at the Oklahoma City Zoo venue in spring 1995.

“At the end of our show she was waiting in her wheelchair with her friends and cousins next to our tour bus so when I walked past she could advance her chair and shout out, ‘Hey Kenny Lee Lewis, I wanna to shake your hand!’ How could I refuse?” Lee Lewis wrote in a tribute to Hughes, who became his lifelong friend, after her passing.

In 2004, Hughes won the title of Ms. Wheelchair America, a position of national public advocacy for people with disabilities that took her to conferences across the country. Her sister, Leeandra Galutia, was with her at the conference where she won the title.

On the first night, when contestants gathered for karaoke, Cinda performed Tanya Tucker’s "Delta Dawn." “And this is not an exaggeration, but she brought down the house,” said Galutia. “She was very charismatic and outgoing, and everyone was entranced by her.”

Cinda’s family and friends say that she died the same way she lived, “with incredible dignity and passion right up until she could no longer function,” Slikkers said.

“She didn't want to be defined by her disability,” her mother said. “She wanted to be defined (by) her tenacity, and her willingness to excel in whatever capacity she could.”

A viewing, followed by a memorial service will be held at 11 a.m. on Wednesday, May 26 at the Church of Latter Day Saints in Alexandria, Va.

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsNavajo Nation Mourns the Passing of Former Vice President Rex Lee Jim

Deb Haaland Earns Endorsement From Communications Workers of America Local 7076

University Soccer Standout Leads by Example

Two Native Americans Named to Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee's“Red to Blue” Program

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher