- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

Back in the 1980s, when video games were young and unwoke, Gen X elementary school students were fed a very one-sided view of westward expansion via the era’s trendy learning game “Oregon Trail.”

In the iconic point-and-click 2D adventure game, the player attempted to lead a settler family traveling with covered wagons and oxen on a trip from Missouri to Oregon. Along the way, they trade for food and supplies, navigate some challenging topography, and try their darndest to avoid dying from dysentery.

In Oregon Trail, which has been reduced to a retro pop culture punchline, the Indigenous characters were peripheral and predictable.

“They were either traders, guides, or would circle wagons and attack. The issue I had with Oregon Trail is that it always put Native people in relation to settlers,” said Anishinaabe, Métis video game designer Elizabeth LaPensée, who teaches at Michigan State University. “The game is all about colonization.”

Fast forward about 40 years, and LaPensée and a team of writers and artists have remixed the tired old Oregon Trail into the Indigenous-focused “When Rivers Were Trails.”

When Rivers Were Trails Trailer from Elizabeth LaPensée on Vimeo.

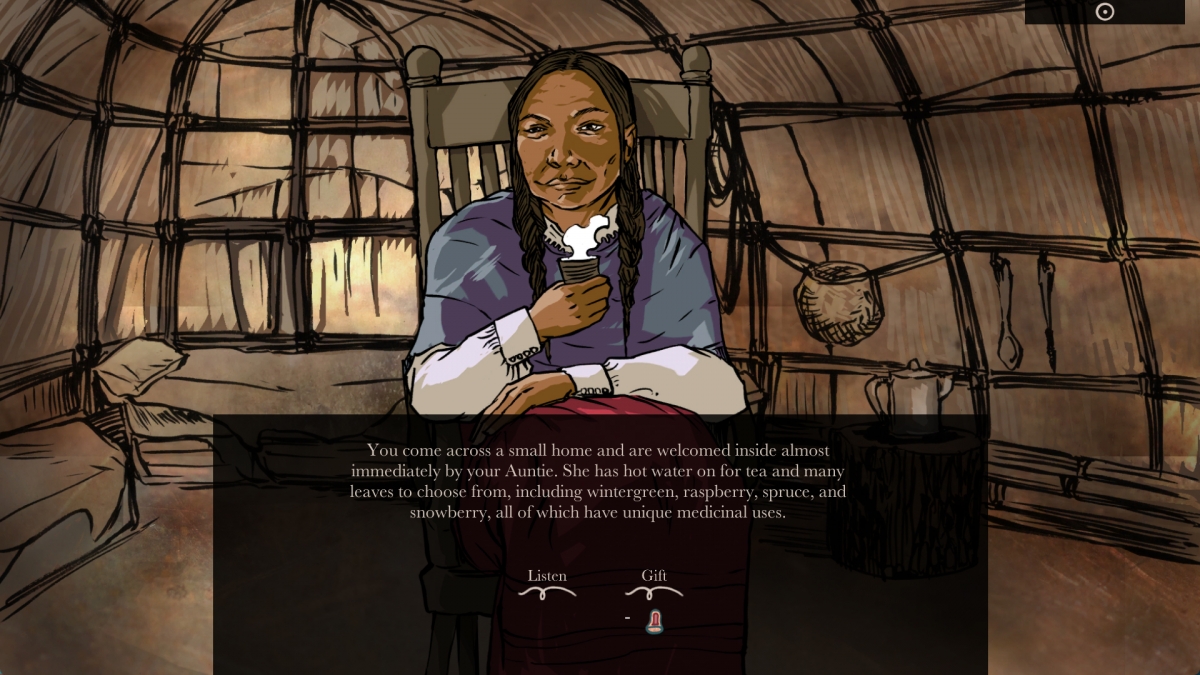

Oregon Trail’s pixelated pioneers and generic storyline have been replaced by artistic, emotionally evocative depictions of Native Americans and historically accurate scenarios.

“The hope was to get a game in schools that shares Indigenous perspectives,” LaPensée said. “I saw issues with how Indigenous people were being treated and viewed and wanted games to do better. We included over thirty Indigenous writers in over 100 character scenarios. Some stories are based on truths and some are directly true.”

In When Rivers Were Trails it’s 1890, instead of 1848. The settler family making their way from Missouri to Oregon is now an Anishinaabeg person trekking from Minnesota to California after being forced from their land.

On the journey, the Anishinaabeg character gathers medicines, hunts for food, dodges incorrigible Indian Agents and meets dozens of compelling Indigenous characters.

The project was born when Nichlas Emmons from the Indian Land Tenure Foundation approached LaPensée about working on a video game based on the Lessons of Our Land curriculum. The Indian Land Tenure Foundation developed the curriculum to include Native American stories, lessons and values in standard classroom instruction.

“I pitched him the Oregon Trail remix angle and he supported it fully,” she said. LaPensée added that the project was funded by the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, which sought to develop a sovereign video game in conjunction with the Indian Land Tenure Foundation.

Judging by the buzz and positive reviews of When Rivers Were Trails, it’s clear that LaPensée and company are changing the video game landscape for good.

The game won the Adaptation Award at IndieCade 2019, a festival celebrating independent video games and was featured at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Annual SAAM Arcade last weekend, prompting The Washington Post to prominently feature it in a weekend to-do list.

When Rivers Were Trails is having a profound effect on some gamers, evidenced by a raving review from the blog Indian Playing.

“Most characters I met through When Rivers Were Trails were Native. Perhaps on an intellectual level it might not seem like a big deal, but I got hit super hard in the feels by the time I made it to ‘Northern California,’” the reviewer wrote. “It was just so touching to see all this Native representation in a piece of media, over and over again, I mean, this is a game made by Native people. It feels like it. I imagine this is what white people must feel when they play… most video games, right?”

Photo by Weshoyot Alvitre.

Photo by Weshoyot Alvitre.

Those impactful images of Indigenous people are the work of Tongva artist and activist Weshoyot Alvitre, a longtime colleague of LaPensée who created all but a handful of the game’s illustrations.

“It was an incredible amount of work and Weshoyot was fully dedicated,” LaPensée said. “Her style is very emotionally strong. You can feel movement in her linework. She works beautifully both by hand and digitally and I’ve always admired her work.”

The idea of updating Oregon Trail instantly appealed to Alvitre, who based some of the California Native characters on her own relatives.

“I knew [LaPensée’s] stance, and I was really excited to work on a project with her leading,” Alvitre said. “I remembered playing Oregon Trail as a kid and the Natives were side characters, they really had no weight in the storyline. I vaguely remember getting excited when the mention of Indians would come into the gameplay, but it was in no way a respectful depiction.”

Alvitre has completely turned those depictions around, delivering a gallery of expressive, complex characters who have much better things to do than trade sweaters with settlers or intimidate them by circling their wagons. There are many instances when the Anishinaabeg traveler passes by Native Americans in conversation about topics from revolt to romantic dilemmas.

In one scenario, a brother and sister are having an emotional exchange by a river. It turns out the girl, whose name is Memengwaa, has developed feelings for another girl. Memengwaa looks down with a frown. Her brother, who is concerned that her preference may cause conflict with white settlers, also wears a worried expression.

Memengwaa is Two-Spirit, which the game defines as someone who understands “gender to be a spectrum and they balance both feminine and masculine aspects.” The player has the option to advise Memengwaa to either forget her feelings or follow her heart.

In another sequence, a crying Mandan mother searches for her son in the reeds by a river. Her boy has been kidnapped and brought to a boarding school. Alvitre captures the searing pain, loss and confusion in the desperate mother’s eyes.

Along with the highly emotional encounters, the game is loaded with illuminating history and facts about everything from the use of traditional medicines to treaties and allotment acts.

“This game is such a celebration of so many stories, so many memories, very personal family histories and some good old fashioned hard work,” Alvitre said.

The artist was delighted by the Washington Post’s description of the game as “a deeper, more soulful Oregon Trail.”

“If Oregon Trail had a soul,” Alvitre countered. “I’m going to start using the heck out of that when people ask me what this game's about.”

More Stories Like This

Chickasaw Holiday Art Market Returns to Sulphur on Dec. 6Center for Native Futures Hosts Third Mound Summit on Contemporary Native Arts

Filmmakers Defend ‘You’re No Indian’ After Demand to Halt Screenings

A Native American Heritage Month Playlist You Can Listen to All Year Long

11 Native Actors You Should Know

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher