- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

As a non-Native reporter covering Indian Country, I probably spend hours each week researching historical context. History frames each and every story we tell at Native News Online. For that reason, I rely heavily on Native media streams to help inform and contextualize my own reporting. Here’s a short list of sources I loved listening to, reading, and watching this year.

Read

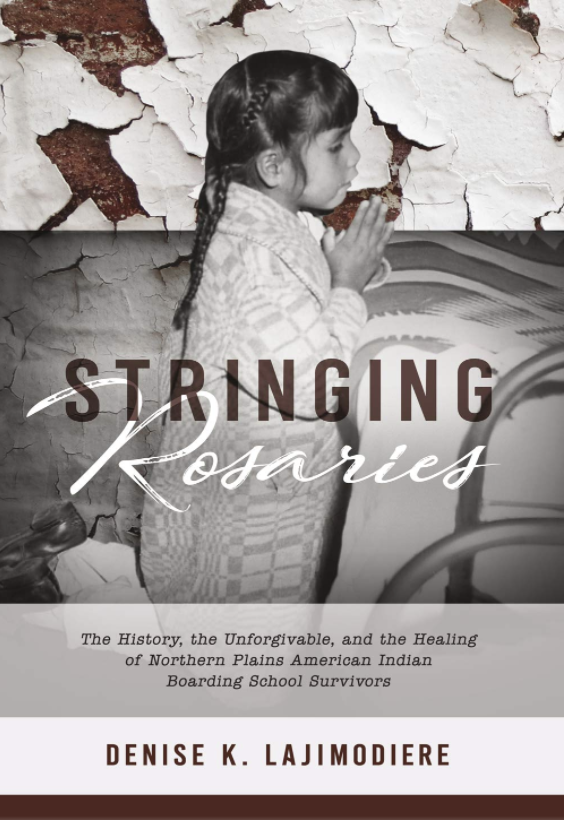

Indian Boarding Schools and their rippling impacts became my beat for Native News Online shortly after the discovery of an unmarked grave containing the bodies of at least 215 school children at the site of a former residential school in British Columbia. In preparation for a trip to Carlisle—the site of the US’s first off-reservation boarding school—I sought advice from Native leaders and sources on what to read. Many suggested Denise Lajimodiere’s (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe) Stringing Rosaries: The History, the Unforgivable, and the Healing of Northern Plains American Indian Boarding School Survivors. In it, Lajimodiere travels through Dakotas and Minnesota, recording over a dozen personal stories of boarding school survivors—in their own unedited voices—describing their experiences.

I recommend this book to other reporters covering Indian Boarding Schools because of the detailed reporting guidelines Lajimodiere includes in the book, but also for anyone interested in making sense of the boarding school era.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

This year, I also read David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI. The book tells the story of 1920’s Oklahoma, where oil discovery on Osage land made the Osage Indians the richest people per capita in the world, and also ultimately the most threatened.

David Grann spent close to five years researching and writing this harrowing history of crime and corruption that led to the formation of the FBI. This book tells a story important for all Americans to know and remember.

Listen

As an avid runner and practiced multitasker, podcasts are the best medium for me to absorb information while also completing another task.

I highly recommend my (full disclosure) former colleague-turned-friend’s podcast on all things contemporary Alaska Native: Coffee & Quaq. Alice Qannik Glenn (Iñupiaq), the voice and the brains behind Coffee & Quaq, leads listeners through a variety of topics explored through an Alaska Native lens.

A few of my favorite episodes include: Decolonizing Beauty, where she discusses what it means to reclaim and revitalize Inuit standards of beauty in conversation with a tattoo artist and filmmaker, and her episode on Alaska Native Mens’ Health and Wellness. Alice and I also collaborated on a series of podcasts back in 2020 that won best audio reporting in an inaugural award ceremony presented by Columbia Journalism Review. That series looks at Inupiat strength and resiliency in the face of an ever-changing environment, reported from the northernmost city in the United States and incidentally Alice’s hometown— Utqiagvik, Alaska.

This year, I also had the pleasure of getting hooked on—and then later interviewing—Rebecca Nagle (Cherokee Nation) for her second season of her podcast, This Land. Season two focused on how the far right media is using Native children to attack American Indian tribes, and ultimately advance a conservative agenda.

In this season’s eight episodes, Nagle takes listeners through the 40-year history of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), sharing her more than a year-long investigation into a current federal lawsuit, Brackeen v. Haaland, spurred by an adoption dispute in Dallas. What Nagle and her investigative team discovered is a well-funded, systemic, far-right operation that is using Native children to attack ICWA, threaten American Indian tribes and advance a conservative agenda.

Nagle covers this story with context every other media outlet leaves out, and it’s enough to make your blood boil.

Watch

The Shinnecock Indian Nation of Southampton, Long Island, were slowly pushed off their ancestral lands and onto an impoverished reservation in favor of wealthy developers turning their homelands into plots for mega-mansions and a golf course that bears their namesake. But New York, unlike most states, doesn’t have laws in place to protect graves on private property, or recourse for what to do when such graves are unearthed.

This recently aired documentary, Conscience Point, follows the story of one tribal member's decades-long effort to protect her tribal lands and ancestors buried there from developers. The documentary costs $5 to stream for 48 hours and is well worth the cost of the information it provides.

More Stories Like This

Two Indigenous Group Exhibits Opening January 9, 2026 at WatermarkWatermark Art Center to Host “Minwaajimowinan — Good Stories” Exhibition

Museums Alaska Awards More Than $200,000 to 12 Cultural Organizations Statewide

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Takes Top Emerging Artist Apprentices to Phoenix for Artistic Exploration and Cultural Immersion

From Dishwasher to Award-Winning Chef: Laguna Pueblo's Josh Aragon Serves Up Albuquerque's Best Green Chile Stew

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher