- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

Two issues were on the table during the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs’ hearing June 22: the Department of the Interior’s landmark investigative report on Indian Boarding Schools, and legislation intended to work in tandem with the department’s initiative to address trauma and bring healing to boarding-school survivors and their communities.

The 106-page report—released last month and penned by Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Bryan Newland—details for the first time the extent of the boarding-school network: The federal government operated or supported 408 schools in 37 states, including Alaska and Hawai’i, between 1819 and 1969. It found that at least 500 children died while at those schools. Newland said he expects the investigation to find that the total death toll was in the “thousands or tens of thousands.”

The report concluded that further investigation, supported by a $7 million appropriation President Joseph Biden has requested from Congress, will be necessary to identify how many children lost their lives, find their names and tribal affiliations, and estimate how much the government spent supporting the boarding-school system.

In response to the report’s findings, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland last month announced “The Road to Healing,” a year-long tour to hear directly from boarding-school survivors in listening sessions throughout the country.

Committee chairman Brian Schatz (D-Hawai‘i) opened the meeting by saying that the committee “must do all we can to right this wrong,” beginning with centering the Native perspective to guide the federal government’s path towards truth and reconciliation.

Members also seemed to support passing the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act, which was introduced by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) in 2020 and reintroduced last year. The bill would establish a commission to investigate the damage and continuing effects left by federal Indian boarding-school policies. It would be empowered to investigate, document, and acknowledge the injustices that led to the immeasurable cultural losses at those schools.

Secretary Haaland called the legislation “complementary to the work” of the Interior Department’s boarding-school initiative.

What Senators Said

There is “no doubt that the impacts are real, and we need to do something about it,” said Sen. Jon Tester (D.-Mont.).

Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) said addressing the harm the boarding schools caused in Native communities was “long overdue.” She said the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act would be an effort “for the United States to step up to address and acknowledge the dark history that we face, but also to go further than that and to help bring healing to Native people.”

Sen. Warren highlighted the Interior Department report’s conclusion that “the federal government has not provided a forum or opportunity for survivors or descendants of survivors of federal Indian boarding schools or their families to voluntarily detail their experiences” in the system.

“My legislation would address this gap by establishing a commission that would have five years to formally investigate boarding schools and to document their enduring impacts,” she said.

“Look, we’re passing this thing,” Schatz said. “Certainly out of committee, and hopefully out of the whole Senate.” But he said the committee also wanted to make sure that the legislation was aligned with what the Interior Department is already doing, “and we're not tripping over a new statute that is not exactly what you already have underway.”

What Indigenous leaders said

Native witnesses testifying included Secretary Haaland; Kirk Francis, chief of the Penobscot Indian Nation; Norma Ryūkō Kawelokū Wong Roshi, head of Native Hawaiian policy for the office of former Hawai'i governor John Waihe'e; and Liz Medicine Crow, president of the First Alaskans Institute.

Through tears, Haaland testified that as both a product of U.S. assimilation policies and as the first Native cabinet member, she’s in a unique position to address the trauma left behind.

“Our obligations to Native communities mean that federal policy should fully support and revitalize Native health care, education, languages, and cultural practices that federal Indian policies sought to destroy,” she said. “The administration strongly supports this legislation, especially the development of national survivor resources to address the intergenerational trauma, and the inclusion of the Commission's formal investigation and documentation practices.”

Haaland said her Road to Healing tour’s first listening session will be held in Oklahoma, where the federal government operated the greatest number of boarding schools. The sessions will have public and private spaces for folks to share their boarding school experiences, depending on their level of comfort in speaking about them, and that the Interior Department is coordinating with local mental health providers to provide support.

She said the department was “working with tribes” to decide where other sessions will be held.

Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-Nev.) asked if the Truth and Healing Act, which would give the federal government authority to subpoena private, state, and local government institutions, would help it gain access to records beyond those in federal repositories.

Assistant Secretary Newland said it would enable the Interior Department to do a broader investigation than it could have done previously, because establishing the commission and giving it subpoena authority would enable it “to seek out that information from non-federal entities and to do a deeper dive, or over a period of time.”

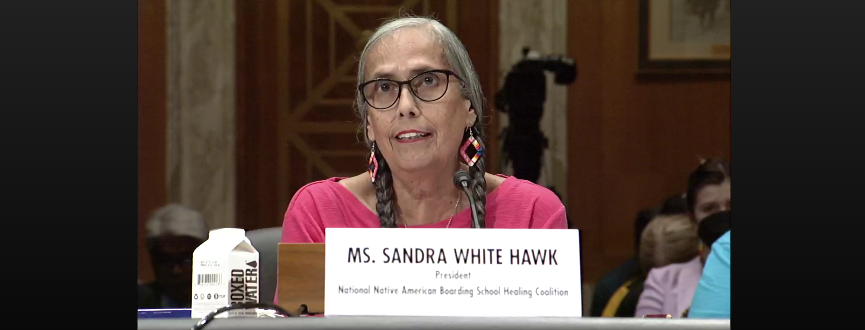

Sandy WhiteHawk, president of the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, testifies. (Screenshot)

Sandy WhiteHawk, president of the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, testifies. (Screenshot)

Sandy WhiteHawk, president of the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, testified that boarding-school survivors being able to share their stories publicly would bring healing.

“It’s one thing to share your story within your home or in your community, but it's another thing to share where it's going to be validated by the outside entities that have brought this on,” she said. “It brings healing in itself. It addresses what we call disenfranchised grief, a grief that’s not been acknowledged.”

Kirk Francis, chief of the Penobscot Indian Nation, testifies. (Screenshot)

Kirk Francis, chief of the Penobscot Indian Nation, testifies. (Screenshot)

Penobscot Chief Francis recommended two revisions to the Warren bill, based on his experience working with the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which examined what happened to Wabanaki families in the state’s child welfare system. He said commission members should be national and regional tribal leaders, rather than government officials, and that Cabinet secretaries should be mandated to conduct consultations about the report’s findings and recommendations.

Francis also recommended that the Interior Department expand its definition of federal Indian boarding schools to include the more than 1,000 government-funded institutions, such as orphanages, day schools, sanitariums, and asylums, that similarly worked to assimilate Native youth into white society.

Liz Medicine Crow, president of the First Alaskans Institute, testifies. (Screenshot)

Liz Medicine Crow, president of the First Alaskans Institute, testifies. (Screenshot)

Liz Medicine Crow testified that her grandmother had told her she could share what she physically endured in boarding school, but that she still isn’t able to talk about what happened emotionally.

“Time is of the essence,” Medicine Crow told the committee. “We cannot waste any more of their precious life with not giving them a forum to share their lived experiences.”

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsTrump Veto Stalls Effort to Expand Miccosukee Tribal Lands

Oneida Nation Responds to Discovery Its Subsidiary Was Awarded $6 Million ICE Contracts

SRMT Child Support Enforcement Unit Delivers Holiday Food Boxes to Families

The Shinnecock Nation Fights State of New York Over Signs and Sovereignty

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher