- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

When two Oyate boys, Edward Upright (Spirit Lake Nation) and Amos LaFromboise (Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate), left their homes in the Dakotas in 1879, they were 13 and 12 years old, respectively. They were each the son of a powerful tribal leader—Amos of Joseph LaFromboise, a founding father of his tribe, and Edward of Chief Waanatan—in line to become hereditary chiefs of their respective tribes when they grew older. Instead, they never left the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania: They both died before they turned 16, and remain buried in the cemetery beside the former school grounds.

This summer, after a century and a half in Pennsylvania, the boys will return home to the Dakotas as leaders, Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate historian Tamara St.John said.

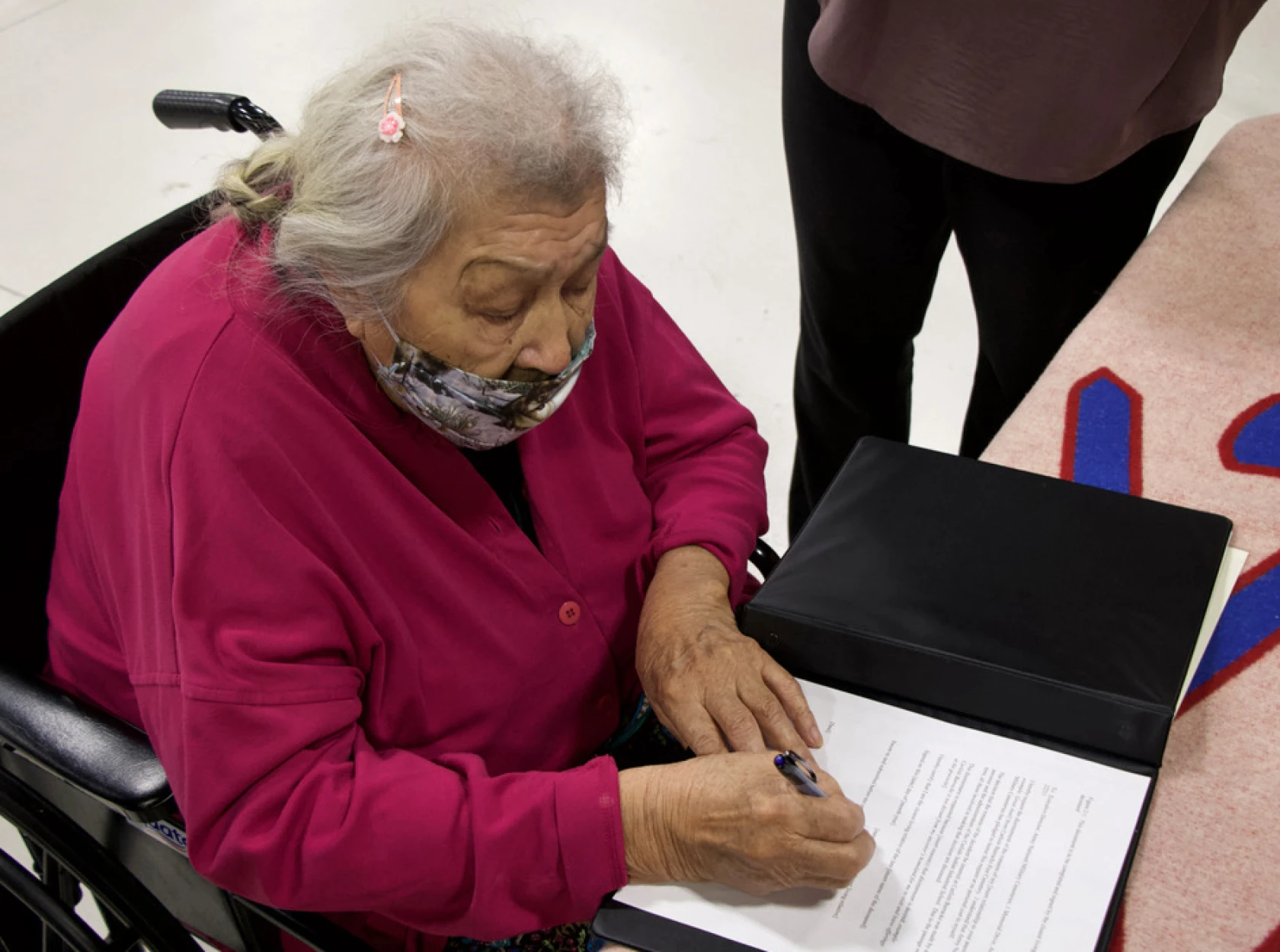

“These boys would be the future leaders had they not lost their lives there,” St.John said in a live-streamed signing ceremony event last Saturday, Feb. 18, at the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate’s casino, Dakota Magic Casino, in Hankinson, N.D.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Last weekend, the tribes took the first step towards repatriating the boys by coordinating the signed affidavits from their direct descendants, a process required by the U.S. Army—which now controls the Carlisle cemetery where 176 Indigenous school children remain buried.

“The Office of Army Cemeteries is aware of the reports that documents were signed regarding the return of children to the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate and Spirit Lake Nations, and appreciates that a visit in September 2021 provided the families and tribes the information needed to reach this step,” the Army wrote in a statement to Native News Online. “Once we receive the required documents for disinterment and the actions are approved, the Army will work with the families to schedule the dignified disinterment and return.”

Beginning in 2017, when Northern Arapaho tribal member Yufna Soldier Wolf successfully petitioned the Army to exhume three of her tribe’s children—also the sons of tribal chiefs— the Office of Army Cemeteries formalized a “disinterment of remains” process for returning Native remains to their lineal descendants.

Since then, the Army has paid for four transfer ceremonies, returning a total of 21 children buried at the Carlisle school cemetery to burial grounds chosen by their descendants. Most recently, the Rosebud Sicangu Oyate brought home nine of their relatives in July.

The Army has scheduled six other children to be returned home this summer, the Office of Army Cemeteries confirmed to Native News Online. St. John, after six years of research, hopes Amos and Edward will be disinterred with them. The Army is also working with families from four tribes—Catawba, Oneida, Washoe, and Umpqua—and two Alaska Native Aleut families for disinterments and returns between June and July, the office said in a statement.

Although the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate worked with the Rosebud all along in coordinating their return, St.John said her tribe got held up locating “next of kin” descendants, because so little information had been kept on the students, particularly Edward Upright.

Upright’s student card notes his tribal affiliation as “Sisseton,” but his family information is misspelled as Wanatah, rather than Waanatan, without any parents or first names attached. St.John would eventually discover that Waanatan was a tribal name from their neighboring tribe, Spirit Lake Nation.

If all goes according to plan, the Army will disinter the boys this summer and they will be returned home to their respective tribes, Spirit Lake Nation Chairman Doug Yankton said on Saturday.

“I believe that come this early summer, or middle summer, we will be putting them to rest respectfully next to relatives at each respective tribe,” Yankton said.

Although the tribe’s focus is on bringing home the two boys, St.John stressed that there are four boys that need memorializing.

“There were four boys that left and all four boys died,” she told Native News Online. “I want to acknowledge all four boys, because they're all important.” The other two Sisseton boys—John Renville and George Walker—are buried at unknown locations on the reservation.

John Renville, son of Chief Gabriel Renville, died in 1880 at age 16 after contracting typhus, according to his student record. “After his death, his father, Chief Gabriel Renville, traveled to Carlisle to retrieve his son’s remains, and then he also took his daughter Nancy back home with him at the same time,” Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center archivist Jim Gerencser told Native News Online.

St.John speculates that the unusual occurrence of a tribal member coming to retrieve their children’s remains was afforded to Chief Renville because of his resources. “He would have had, even before the Dakota War, a farm and businesses,” she said. “I could see where he would have resources that nobody else would have.”

George Walker, the fourth Sisseton-Wahpeton boy who arrived at Carlisle in 1879, was sent home due to his health in April 1883, according to school records. St.John said his death was confirmed in written correspondence between Carlisle officials. “Whatever illness was with him then followed him all the way home,” she said.

Amos LaFromboise was the first student to die at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, just 30 days after he arrived there. Records show he was originally buried in a local cemetery in Carlisle, but was reinterred at Carlisle two months later because the local cemetery was restricted “for the burial of such White persons.” His cause of death isn’t listed.

Edward Upright died of pneumonia, after recovering from measles, according to a letter from his physician to Richard Pratt, the school’s superintendent.

Until Edward and Amos are confirmed for disinterment this summer, St.John said she’ll be nervous.

“I feel afraid of how much it's going to hurt,” she said. “I feel afraid for my community and the relatives because it will bring out pain and hurt. After that, I feel excited and happy that things are moving and progressing. And then I feel proud, really proud of our families and our tribes and how we just connected and embraced each other in this and in this difficult thing.”

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal Relations“Our Sovereignty Is Not Optional”: Tulalip Responds to ICE Actions

Denied Trip to Alcatraz, Leonard Peltier Tells Sunrise Gathering: “My Heart Is Full”

‘Meet your prayer halfway’ | Women-Led Bison Harvests Bring Tribal Food Sovereignty

San Manuel Tribe Reclaims Ancestral Name, Faces Vandalism on Holiday

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher