- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

The American Bar Association earlier this month hosted a conference, highlighting different tribal, federal and private agencies working to restore ancestral Native lands to tribal nations.

The one-hour session speakers included: Carolyn Drouin, an advisor for Tribal Relations with the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Land Buy-Back Program for Tribal Nations; Chris Stainbrook (Oglala Lakota), president of the grassroots organization working to help recover and manage reservation lands, the Indian Land Tenure Foundation; and Koko Hufford, land project manager and enrolled tribal member at the Confederated Tribe of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The panel was moderated by lawyer Kathy Kinsman, whose legal experience includes Indian Law. Kinsman also co-chairs the American Bar Association’s Native American Law Committee.

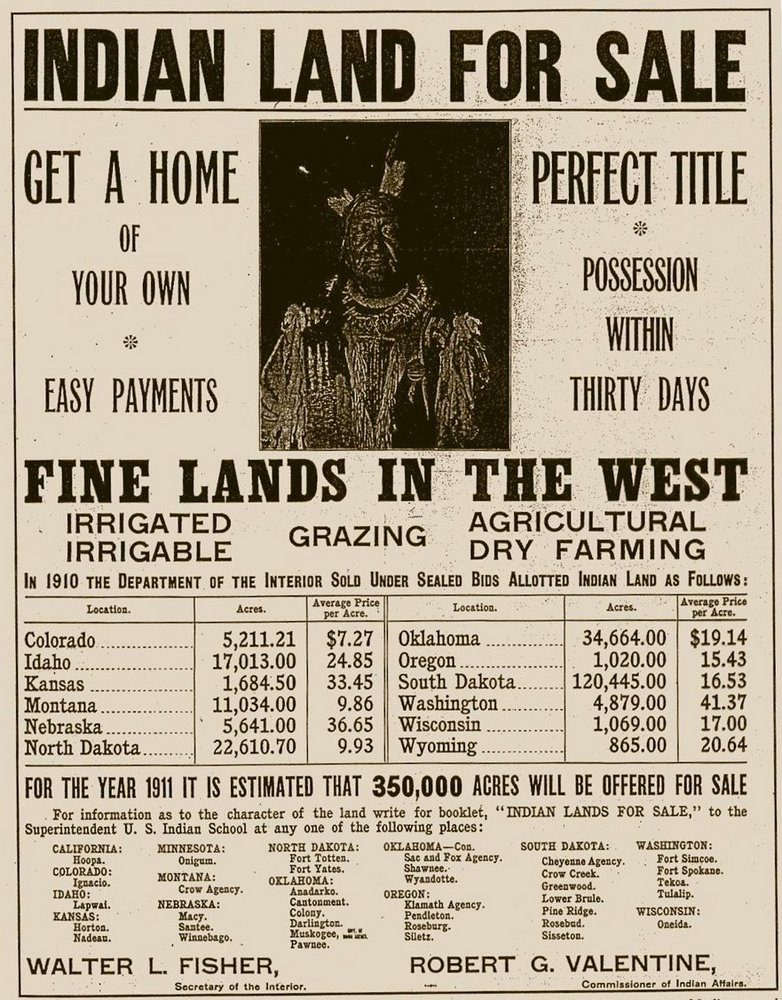

Initially, most tribal nations ceded large swaths of their land in binding treaties with the US government, in exchange for certain protections and sovereignty. The government disregarded or reneged on most of those early agreements, and split up reservation land in the 1887 General Allotment Act. The Allotment Act, passed by Congress exactly 135 years ago this month, divided up reservation lands into individually-owned parcels and forcibly sold the remaining “surplus” land to non-Native homesteaders. As a result of the allotment policy, more than half of the land on Native American reservations in the U.S. is privately owned and controlled by non-Natives.The lost land equates to 90 million acres.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Several Native Nations, in partnership with the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, have been working to get ancestral lands back into tribal hands for more than two decades. Buying back Indian land is complex that involves the Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs, tribes, and sometimes tribal citizens.

The Indian Land Tenure Foundation, led by Stainbrook, started their work in 2003 by helping tribal members write wills and organize estates to ensure Native land is kept in Native hands.

“Ultimately, the goal is to get that 90 million acres back in Indian ownership, management (and) control, plus those sites outside of the reservation that are important for cultural purposes to the tribes,” Stainbrook said on Thursday. “Over the years, we’ve recovered roughly 100,000 acres…and by the end of March, we should have another 50,000 acres recovered.”

For the federal government’s part, The Department of the Interior in 2013 began the Buy-Back Program, aimed at consolidating Native lands from “fractionation” over a ten year period with almost $2 billion. That period ends this November. The Buy-Back Program was created to implement the land consolidation component of the Cobell Settlement, which provided $1.9 billion to purchase fractionated interests in trust or restricted land from willing landowners. Consolidated interests are transferred to tribal government ownership for uses benefiting the reservation community and tribal members.

Fractionation, Drouin explained, is the result from the policy of breaking up tribal homelands into individual allotments or tracts and then dividing its ownership among more and more owners after the death of the original owner.

“On average, each tract has 25 owners,” Drouin said. “We've seen some tracts that have in the hundreds and even some tracts that have thousands of landowners.”

Native News Online founder Levi Rickert said that, around 2013, the Department of the Interior was getting multiple family members who were claiming stake in land after their relatives died.

Fractionation makes it harder for an individual person or a tribe to pursue economic development opportunities and infrastructure projects on lands when there are hundreds of people that need to be involved in making a decision, she said.

So far the Buy-Back program has consolidated over 1 million fractional ownerships (not necessarily full acres) which has resulted in 2.9 million equivalent acres transferred to tribes and trust, Drouin said.

As a result, landowners and tribes have reported an improved ability to pay off debt and utilize the land for economic growth.

“The Oglala Sioux Tribe is collaborating with USDA to develop agricultural improvements including the creation of more reliable sources for livestock,” Drouin said. She added that the Makah Tribe used its consolidated land to build a recreational facility and cabins to generate further income for the tribe.

Hufford, who works in her tribe’s land department in Oregon, said the Umatilla Indian Reservation has used funds from its tribal farming enterprise to buy back land lost during the allotment period.

“Now we own about 100,000 acres of our own property,” Hufford said. “One thing is, we couldn’t have done this without our partners. I could talk badly about the Department of Interior and the BIA, but they had to be our partners. We had to work with them to make it happen.”

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsHomeland Tour Offers Deeper Understanding, Appreciation of Chickasaw Roots

Klamath Tribes Seek to Reverse Judge’s Removal in Water Rights Case

Tunica-Biloxi Chairman Pierite Elected President as Tribal Nations Unite Behind New Economic Alliance

NCAI, NARF Host Session on Proposed Limits to Federal Water Protections

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher