- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

Last summer, the Department of the Army, which controls the site of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, said it “stands ready” to assist any tribe or family member who wishes to disinter their relatives and bring them home from the cemetery there.

In 1879, what was then the Carlisle Barracks became the site of the nation’s first Indian boarding school, which was operated by the Department of the Interior until 1918. During those 39 years, it forcibly assimilated 7,800 Native American children from more than 140 tribal nations through a mix of Western-style education and hard labor. At least 194 children from 59 different tribes died there, of disease often made worse by poor living conditions and abuse, and were buried at the school.

Exhumations from the Carlisle Barracks Post Cemetery began in 2017, when Yufna Soldier Wolf of the Northern Arapaho Tribe won her 10-year battle to return three Arapaho children. They were reburied on the reservation in Ethete, Wyoming.

The Army has since returned a total of 28 children in five disinterment projects. Each project was conducted for about a month during the summer. A team of professionals from the Army Corps of Engineers’ Center of Expertise for Curation arrives to carry out the process of exhuming and identifying each child’s remains.

The team consists of 13 people: three tribal liaisons, who oversee family coordination, tribal consultation, and travel logistics; three specialists from the Office of Army Cemeteries, who oversee the site layout, manage all the equipment, and ensure security and privacy; three forensic archaeologists, who exhume the remains; and four biological anthropologists, who conduct forensic analyses on the remains to ensure they match their description.

The Army spent over $600,000 in each of the past two summers — 2021 and 2022 — to return seven to ten children, according to spokesperson John Harlow.

However, at least 171 children are still buried at the Carlisle Barracks, according to records kept by the Carlisle Indian School Digital Research Center, run by Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Fourteen of those children are under headstones marked “unknown.”

Based on the Army's current projections and the pace of disinterment, it will take 17 years and about $10.2 million to return each child from the Carlisle cemetery, if every child is claimed.

To help elucidate the process, Native News Online spoke with a few relatives who have successfully brought their ancestors home from Carlisle, plus a spokesperson from the Army.

Step 1: Locating your relative

According to Renea Yates, director of the Office of Army Cemeteries, the Army notified all 574 federally recognized tribes that it had Native children buried in its cemetery back in 2016, and will do so again this fall.

The Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center has been digitizing Bureau of Indian Affairs documents kept on the school and its students for eight years. As a result, anybody can search through detailed student records, which include their age, tribal affiliation, family background, admission and discharge dates, school activities, health reports, and even sometimes school newspaper clippings.

For those unsure of whether they have tribal relatives buried at Carlisle, there is also digitized cemetery information that includes the deceased’s dates, plot location, and primary documents on the death and burial of a student.

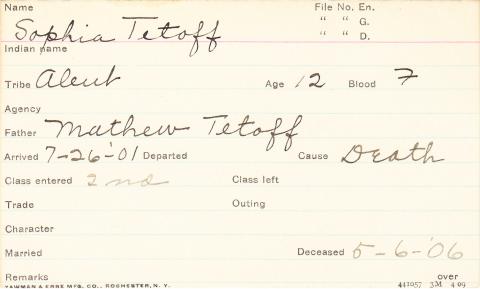

In 2021, Lauren Peters (Agdaagux Tribe) successfully brought her great-aunt, Sophia Tetoff, home to Saint Paul Island in Alaska. She told Native News Online that the Digital Resource Center was a critical resource for gathering the information she needed. She recommends asking archivists there for help navigating that information.

“If you contact Dickinson [the Digital Resource Center] directly, they're very open about leading you through the database, and how to find all the different pieces of information,” Peters said. She warns that name misspellings and incorrect tribal affiliations listed in the documents could have derailed Sophia’s return.

Sophia, who was about 17 years old when she died in 1906, was a member of the Unangax Nation, but her student card garbled that, listing her as part of the “Aleut” tribe. “So if I had visited the cemetery, I might not have put those two things together,” Peters said.

Student information card of Sophia Tetoff, a member of the Alaskan (Aleut) Nation, who entered the school in June 1901 and died there in May 1906. She was buried in the cemetery on the school grounds. (Photo: Courtesy Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center)

Student information card of Sophia Tetoff, a member of the Alaskan (Aleut) Nation, who entered the school in June 1901 and died there in May 1906. She was buried in the cemetery on the school grounds. (Photo: Courtesy Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center)

Step 2: Initiating paperwork

The Army has made clear that it does not believe it is compelled to repatriate human remains under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), because the Carlisle Barracks Post Cemetery does not constitute a “collection.” Many tribal Nations and Native attorneys dispute that.

Instead of following NAGPRA, the Army follows its own rule for exhuming Native American remains: Army Regulation 290-5, which requires that a lineal descendant make the request for disinterment.

“Under Army policy, and because we have the custody of the remains, we have to allow the family to be the one that notifies us,” Renea Yates said during a press conference last year. “Tribal requests cannot be made. It has to be the individual closest family member.”

How to find the closest living relative

In several instances, tribal historic preservation officers have been able to locate the closest living descendant through their surnames, research provided from the Digital Resource Center, and consulting with tribal elders.

For a few disinternments during the summer of 2022, the Army contacted the Alutiiq Museum in Kodiak, Alaska. The museum took on the role of locating the next of kin for three Alaska Native girls. Relatives of Anastasia Ashouwak, who went home in July, used Ancestry.com to prove their lineal relation to her.

“The most significant question to answer and/or research is the family tree and who is the ‘senior’ living descendent that is able to take responsibility for claiming the remains,” Lara Ashouwak, whose husband, Ted, is related to Anastasia, told Native News Online in an email. “We were lucky because I had worked on Ted's genealogy and already knew the answers re: who was who, our relationship to Anastasia, and the line of seniority.”

What happens if you can’t find a closest living relative?

This is where the process can get a bit tricky. One girl buried at Carlisle was unable to be returned home in 2022 because the museum responsible for initiating the returns couldn’t locate a living descendant. In such instances, the Army requests that a tribal official contact them directly.

“The Army recognizes that almost none of the Native children buried at CBPC [Carlisle Barracks Post Cemetery] had detailed parent information listed on the school burial records,” spokesperson John Harlow told Native News Online. “The closest living relatives of the deceased may only be distantly related. We understand that Native American Traditional Knowledge may likely be the basis to determine who is the closest living relative.”

What to do once you’ve found the closest living relative

Tribes who have found the closest living relative can request disinterment by submitting two documents to the Office of Army Cemeteries. One is a notarized affidavit by the closest living relative of the decedent, requesting the disinterment and including the reason for it. The other is a notarized sworn statement by a person who knows that the person who supplied the first affidavit is the closest living relative. Requests should be emailed to: [email protected].

Yufna Soldier Wolf, the Northern Arapaho tribal member who was the first to return her relatives from Carlisle, created a 23-page document summarizing the Carlisle disinterment process as a tool for other tribal nations. She recommends getting your paperwork in early.

“Plan to get it in before Christmas,” Peters echoed. “And if you can't, lower your expectation that this is going to happen in six months.”

Planning for the next year’s disinterment project begins around the 4th of July, as soon as the current year’s project is complete, Harlow said. “The detailed planning, preparation and funding is completed by 15 January of each year in order to publish the list of children for disinterment in the Federal Register and properly plan for the families to travel to Carlisle for the next planned disinterment,” he added.

Anastasia's descendant, Ashouwak, carries her remains to the cemetery for reburial after a long journey home this summer. (Photo: Brian Adams)

Anastasia's descendant, Ashouwak, carries her remains to the cemetery for reburial after a long journey home this summer. (Photo: Brian Adams)

Step 3: The Return

Once the Army receives and approves your paperwork, they will put you in touch with someone to coordinate logistics, Lauren Peters said.

She said it connected her with a tribal liaison, and led her through an orientation over Zoom prior to her trip to Pennsylvania. It included details on what the disinterment will look like, how the transfer will be set up, what your privacy will be like. Family members can choose which cultural protocols for the ceremony they want, and who will be allowed to come in and out of a secure tent during the ceremony.

The Army reimburses the cost of travel and expenses associated with the exhumation and burial, but only for two people. Peters recommends getting clear assurances ahead of time about what costs will be reimbursed. It cost $18,000 for her and her son to travel to Carlisle, plus a second leg for her and an additional son to go to St. Paul’s Island in Alaska. The Army reimbursed her for $12,000, she said, and she got the balance covered through a grant from her university.

Funding is “a tough one,” Peters said. “Know that you might have to do some fundraising. I think if your expectation is that [the Army is] gonna take care of everything—and I think we all feel that they should, for as many people that need to go out there and witness it—[you’ll see] that’s the difference between being a tribal government and the U.S. government.”

Soldier Wolf recommends that family members ask the Army ahead of time for a printed packet of information and guidelines, so they can know what to expect. She also recommends having someone knowledgeable in archaeology and anthropology to walk the tribe through the process on the ground. “If the tribe repatriating doesn’t agree or want things done differently, they have the person who can help them understand and communicate to the Army how the tribe wants it and then move forward,” she wrote.

Peters said that the team working to disinter Sophia was exceptionally respectful, and didn’t make a single decision without first consulting with her.

“Any time there was the slightest question, they stopped everything and they came to me and my son, and they asked: How do you want to do this?” she said. “Sometimes there was a delay while I called up to St. Paul, and that was totally fine with them.”

What surprised Peters most about her trip was how she felt once the process was set in motion.

“All the right things were set up, but still I didn't anticipate the panic attack I had on the airplane on the way there,” she said. She recommends preparing a support system for yourself while you’re in Carlisle, spending time in nature, and possibly planning to speak to a talk therapist or a spiritual leader once the process is completed.

The community of Old Harbor, Alaska, gathered in July to rebury Anastasia Ashouwak beside her relatives. (Photo: Jenna Kunze for Native News Online)

The community of Old Harbor, Alaska, gathered in July to rebury Anastasia Ashouwak beside her relatives. (Photo: Jenna Kunze for Native News Online)

Step 4: The Reburial

Each tribe that has completed disinternments from Carlisle navigated their reburial process differently, but many tribal nations organized large gatherings for their ancestors’ reburial on their homelands. Some family members, including Lauren Peters and Lara Ashouwak, have sought permission from the bishop of the Orthodox Church in Alaska to have the church participate in their ancestors' welcome home and reburial.

Soldier Wolf recommends that, no matter how you and your tribe decide to handle reburial, make sure you have a plan in place for how to address the media.

“Our tribe has a media policy and procedure they follow along with our elders’ tribal protocol for do’s and don’ts for the media,” Soldier Wolf wrote. “Without any of this guidance, it would have been a lot of stress for me to deal with, as I had all types of famous and local news agencies calling for stories and interviews.”

She recommends implementing a media plan to determine who will speak; following a process or assigning a person to respond to media requests; ensuring that elders and descendants are okay with the plan, and reassuring them you are doing this for their privacy; and making consistent responses to the media.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to reflect the correct age of Sophia Tetoff, who was about 17 years old when she died in 1906, as well as the number of children whose remains has been returned and the timing of the Army's outreach to federally recognized tribes about the Native children buried in its cemetery.

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsNavajo Nation Council Members Attend 2025 Diné Action Plan Winter Gathering

Ute Tribe Files Federal Lawsuit Challenging Colorado Parks legislation

NCAI Resolution Condemns “Alligator Alcatraz”

NABS Documents 134 More Survivor Stories, Expands Digital Archive in 2025

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher