- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

When the news broke last May of a First Nations tribe in Canada using ground-penetrating radar to discover 215 unmarked graves of children at the site of a former Indian residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia, major media outlets all over the world picked up the story, but very few explained what ground-penetrating radar actually is and how it’s used. Native News Online included.

We remember Googling “ground-penetrating radar,” and reading a jargon-filled definition about geophysics and radio waves. Like many other journalists around the world covering this story, we avoided an in-depth explanation of the technology.

Instead, we wrote: “The tribe hired a specialist in ground-penetrating radar to find the gravesite during a site survey on its property.”

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Now, with the federal initiative underway and an increasing number of tribes doing their own work to locate unmarked gravesites at former boarding schools, it’s time for an in-depth explainer on what exactly ground-penetrating radar—called GPR for short—is, how it works, and how tribes can gain access to a unit.

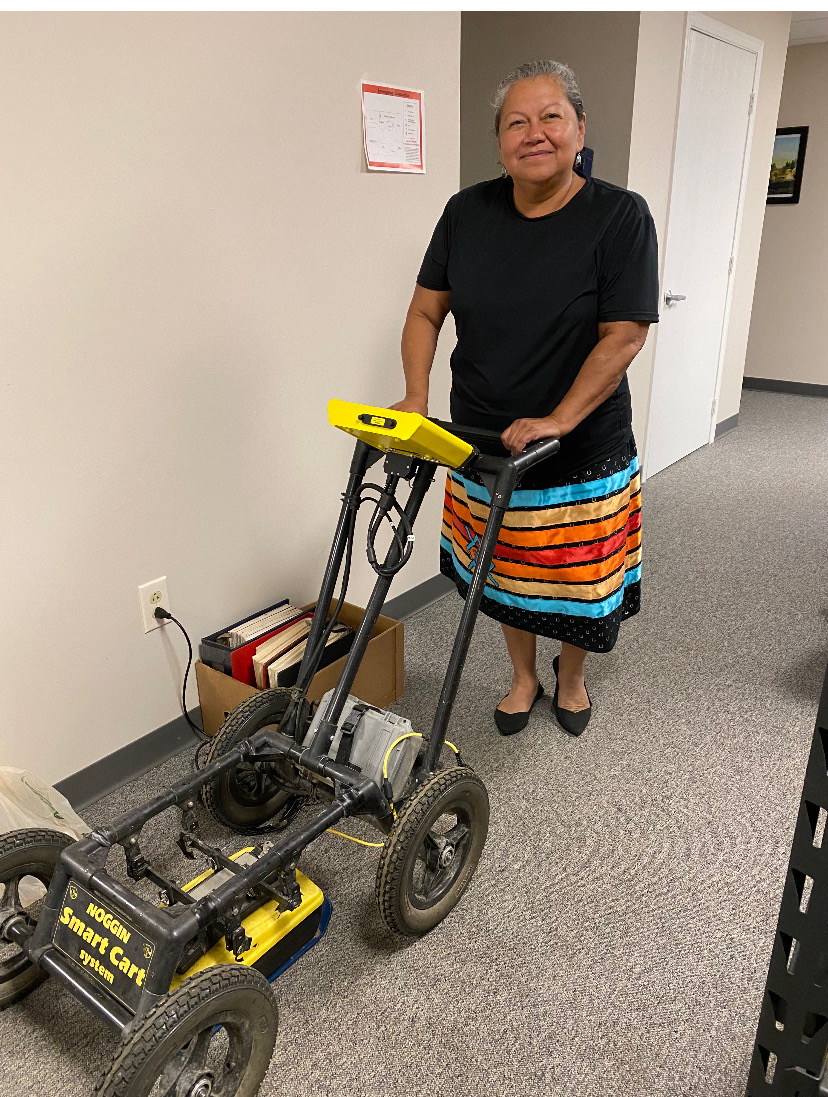

Native News Online spoke with Marsha Small (Northern Cheyenne), a doctoral candidate at Montana State University who has been working with ground-penetrating radar for almost a decade. She is researching its use to locate and document deaths at two Indian boarding-school cemeteries: Chemawa Indian School, north of Salem, Oregon, and another school, located on-reservation, where Small agreed with the tribe she’s working with to keep their identity confidential.

Since 2014, Small has been surveying the cemetery at Chemawa, the longest-running Indian boarding school in the country. Opened in 1880, it is still operating today, now under the federal government’s Bureau of Indian Education. She located 222 unmarked graves, more than the 208 that records said existed there.

Speaking with Native News Online, Small used her knowledge of ground-penetrating radar and her experience as an Indigenous practitioner to explain what it is, how it works, and why a tribe might want it.

The interview has been condensed for the sake of brevity and clarity.

Native News Online: Can you explain what ground penetrating radar is?

Small: Ground-penetrating radar is a geophysical instrument that is considered noninvasive and non-disturbing. A simple explanation is: When soil is disturbed, the radar, or an energy that goes into the subsurface, picks up the variance in the physical properties and chemical composition of the soil. It will more than likely show the anomaly, or someone’s child, and the energy is reflected back up into the machine’s data logger. That is how we determine depth [to where someone is buried].

Native News Online: How else is GPR used, outside of this work surveying graveyards?

Small: It started out as a geology instrument. Archeologists started using it in 1998 because it was cost-effective… because it’s non-disturbing. [Otherwise], you could go in, dig the whole site, and your findings [might] be zilch. They started using it extensively around about 2005. I started seeing a lot more literature after that.

Native News Online: Why is it a particularly important tool for the work of surveying graveyards containing the remains of Indigenous children?

Small: The way that it [operates] reflects multiple indigenous values: noninvasive and non-disturbing. For many tribes, [that] is considered pretty empowering. But on the other side of that coin, some tribes believe the energy is invasive and disturbing. So it depends on the tribe.

Native News Online: How much does a GPR machine cost?

Small: A basic unit can cost anywhere from $25,000 to $40,000, [depending] on the survey’s needs. Some less expensive antennas are used for shallower search surveys; some that cost more are used for deeper surveys. In the geophysical surveys that I have been doing, we have been including multiple instrumentation. One is not good enough working alone. It can often miss data… not because of the instrument's fallibility. It's either the soils, or it's weather conditions, or it can be soil water content.

Then, in addition to the machine, you need a professional surveyor to analyze the “hyperbola,” or the machine's findings, to determine what the anomaly underneath the soil might be: tree roots, burial objects, or human remains.

Native News Online: What are the pros of using this tool? The cons?

Small: Cost. It can be viewed as a negative, but in reality is probably a positive, because it doesn't take as much time as a full excavation. It's still pretty spendy for tribes to buy into. It’s still a really big request.

Native News Online: Can you share your philosophy on the importance of having an Indigneous practitioner running the survey, or at least a Native person walking the grounds alongside a Non-Native practitioner?

Small: It's critical to have an Indigenous researcher doing this GPR. If you can't find one, then have one walk with you every bit of the way. Explain to them what is going on, and they will develop the seeing… and hearing, and they will be able to add incalculable amounts of data to the final product. We need to reclaim these children and to rematriate them in our ways, because they were stolen from us in the other ways. We need to bring them home, under our guidance, with our voices, not in voices they don't understand.

These children were forbidden to speak their languages. So to bring them back, we're not going to use English to do this.

I've been through this for seven to eight years. Doctors Preston McBride and Farina King, and I developed a set of protocols that were edited by Dr. Jarrod Burks at Ohio Valley Archeological Inc., a business that specializes in the application of geophysical instrumentation in search for graves. I've been working with different agencies—federal, state, tribal—and this is what I've learned.

Native News Online: What are your biggest words of advice for tribes looking to do this work theSmallelves?

Small: Be careful. [Non-Native] practitioners, their thinking is not like ours. They haven't undergone the loss of those children and the epigenetic stressor of the loss of those children. They don't have the epistemology to navigate this, they really don't. And I'm not trying to be critical. I'm just stating what is.

***

For tribes interested in learning more about where to get access to GPR units, Small said Washington State University-Vancouver professor Colin Grier—who has worked with tribes for more than 30 years —is a good resource. Grier told Native News Online that some universities that own their own machines collaborate with tribes to do both the training and the surveying work. “We need to work to get these machines in the service of tribes, but there’s a steeper-than-ideal learning curve to produce high-quality results,” he said. “So a key goal is to get machines, and training in how to use them, out to tribes.” Some tribes, such as the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, have outright purchased a unit to begin their own surveying. Small and a few other colleagues have written protocols for practitioners interested in taking on the work. Those protocols can be read here.

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement ActivitiesChickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher