- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

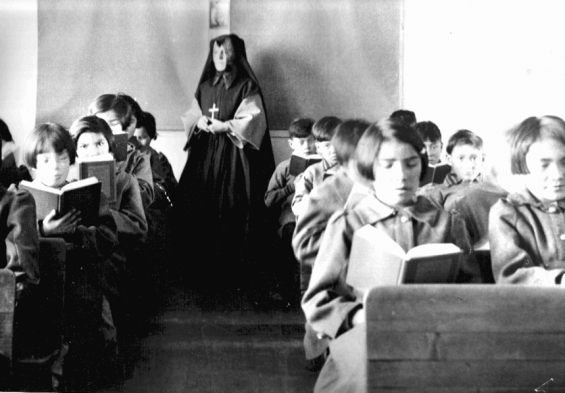

An increasing number of Catholic organizations are joining the discussion about Indian boarding schools. But what role do they have to play in the pursuit of truth and healing, and who is their participation serving?

In November, Archbishop Paul Coakley of Oklahoma City, chairman of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee on Domestic Justice and Human Development, and Bishop James Wall of Gallup, New Mexico, chairman of its Native American Affairs subcommittee, sent a letter on behalf of the organization to all U.S. bishops, encouraging them to initiate truth and healing discussions with local Nations.

“We encourage you to consider reaching out to local Tribal leaders, and begin, if you have not already done so, a dialogue about the schools that were historically in your areas, as well as any that continue in operation,” the letter said. “The second goal of such a dialogue is to discern where reconciliation is needed and what form it might take.”

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

The letter also encourages bishops across the country to comply with the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, launched in June by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. “If the federal government asks for any records you may possess, we encourage cooperation,” Coakley and Walls wrote. “If there is a request from the government to enter Catholic property and investigate historic graves, we would encourage cooperation.”

The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City also recently launched a project aimed at understanding its own history with the Catholic Indian boarding schools in Oklahoma. Oklahoma hosted the greatest number of Indian boarding schools in the country—at least 83, according to data collected by the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, the group at the helm of the truth-and-healing work associated with those schools.

The state ran 11 of the Indian boarding schools, though historians note that, even in government-run schools, there was Catholic influence. The last Catholic Indian boarding school in Oklahoma, Saint Patrick’s in Anadarko, closed in 1965.

What is the initiative?

The work of the initiative, called the Oklahoma Catholic Native Schools Project, is twofold. Part of it focuses on historical document research, and the other on collecting survivors’ experiences.

The project’s coordinator is Michael Scaperlanda, the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City’s chancellor and a retired law professor at the University of Oklahoma. He told Native News Online that the initiative will likely take a year.

For the research, the Archdiocese has enlisted the volunteer work of professor Bryan Rindfleisch of Marquette University in Milwaukee, where records from the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions are kept.

Rindfleisch, who specializes in Native American history, says he expects the records to reveal violence that took place in Indian boarding schools.

“The very nature of boarding schools is violence, whether that's cutting hair, asking you to give up your religion, and talking about restricting religion and adopting Catholicism,” he said. “You see that all in the record. So I'm just assuming violence is there.”

Rindfleisch told Native News Online that there are “hundreds of thousands of documents” on just the Oklahoma boarding schools. He will be responsible for writing a report with his findings. Scaperlanda said that report will then be made public.

The second part of the project, collecting oral histories, has already begun.

In October, Catholic Deacon Roy Callison (Cherokee Nation) began hosting “listening sessions” along with his wife, a member of the Choctaw Nation, to hear from Oklahoma boarding school survivors and their descendants. Callison said the two were inspired after the news of the mass grave of unmarked children being discovered in Canada, and he thought he could help gather some information for his own population.

Eventually, Archbishop Coakley contacted the couple to help lead the Oklahoma Catholic Schools Native Project in continued listening sessions. Callison hosted the fifth one on Jan. 9, and says they won’t stop until he’s visited every region of the state.

“There's no training required because basically what we do is we go into the parish, and I'll usually assist in Mass, and then we'll have a listening session after in one of the parish halls. I just explain to them that we're wanting to document this to find out anything that went on in Catholic Native American boarding schools, and they know I'm recording it, and they're free to just speak whatever's on their mind.”

Callison said that, so far, he’s mostly heard from descendants of survivors, and he’s mostly heard about positive experiences.

In the coming months, Scaperlanda said, the Native Project also plans to document the oral histories of boarding school survivors and their descendants, collected by University of Oklahoma PhD candidates.

“My assumption has been by having professionals under a professor at the University of Oklahoma, that they would receive whatever training was necessary by nature of their academic program,” he said. “And they will receive the best practices (and) training coming from indigenous communities.”

Tribal response

While Native leaders support the message sent by Coakley and Wall in their letter to the bishops, they also urge “extreme caution.”

After the letter was sent out in November, the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) released a statement saying it has been “calling for churches to share their records for years, and there cannot be any further delays.”

“Churches also need to understand that in this process of truth and justice a basic principle is not to cause any further harm—this includes being self-serving in seeking absolution,” the statement said. “This is a time for survivors, Tribal Nations, and Indigenous people to lead on this issue and center their own healing, so we urge extreme caution in churches reaching out to survivors, beginning healing initiatives, recording stories, or centering their perspectives and interests on this history. The churches are perpetrators in these genocidal crimes against humanity, so they should act as such in all their communications with the victims and survivors.”

‘A good first step for the church to take’

On the other hand, some believe the Catholic church has a responsibility to right its wrongs, though keeping in mind the best practices on how to do so.

Maka Black Elk (Oglala Lakota Nation)—the executive director for truth and healing at the Red Cloud Indian School, a former boarding school in Pine Ridge, S.D.—sits on the board of the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, where his main role is to serve as a liaison to the Catholic church.

“The Catholic Church ran numerous amounts of these schools and have, by far, the greatest share of any denomination of Christianity,” he told Native News Online. “There is still a deep schism in the community… between the Catholic Church and Native peoples that I personally believe needs healing.”

Since Red Cloud began its work—the first project of its kind—in September 2020, Black Elk said they have learned a lot about protocol.

“We really see the importance of having those kinds of difficult conversations about: what does it look like for the Catholic Church to remain active in Indian Country? What should look different? How should the Catholic Church really address this history in a more active way, instead of a more passive way?” he said. “NABS was a great resource for this… when it comes to eventual collection of stories, and engaging with survivors and alumni, we need to have mental health, spiritual health, and support available and ready.”

Overall, the bishops’ November letter was an important step towards healing, Black Elk told Native News Online.

“I think this is a powerful first step for the church to make this effort to say, you all need to know about the history,” he said. “If you have tribal communities in your diocese today who have this history in your diocese, you need to start finding out this basic information.”

To explore Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition’s resources on curriculum, reading, and research, visit their website.

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement ActivitiesChickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher